Dune: Spice Wars review - a good strategy, but an underwhelming adaptation

Bookwormed.

Early Access can seem like the prescience of Paul "Muad'Dib" Atreides, the saviour, prophet, and eventually emperor in Frank Herbert's series of Dune novels. As a game releases into Early Access, you can see the possibilities ahead of it, the design decisions it might and might not incorporate, the vague outline of the finished work. As Early Access progresses, the possibility space narrows; the outline solidifies.

But if there is one theme to take away from Herbert's work, it is that seeing the possibilities does not necessarily enable one to make the most of them. Paul rose to be the messianic leader of the Fremen, the indigenous people of Arrakis' deserts living under the boot of House Harkonnen and the imperial House Corrino that licenced their occupation, but his rise was irrevocably tied to billions of deaths across thousands of planets.

The extremes aren't quite so dramatic in the case of Dune: Spice Wars, but it's hard not to wonder what it could have done differently. The Early Access release in April 2022 already offered a polished and intriguing foundation - a moreish 4X gameplay loop hooked around just enough of Herbert's lore to suggest that in time Spice Wars could do justice to the depth and strangeness of his work. The full release maintains the compulsive gameplay and polish, but proves those grander hopes largely unrealised.

Admittedly, Herbert grappled with many complex ideas: not only Paul's legacy as a failed leader, but the implications of prescience and prophecy for free will and human progress. The impact of Paul's and his predecessors' terraforming programme on Fremen culture and way of life. The interdependency of ecosystems as Dune's giant sandworms, unable to survive outside the desert, were revealed to be the source of its most precious commodity - the Spice Melange, which enables the Spacing Guild's Navigators to chart safe passage between the stars by enhancing their prescience. The fragility of monopolies as the Guild, and by extension the entire Landsraad council of the galactic great houses, were brought to kneel by Paul's control of Dune. The exploitation of ideology and religion, cloak-and-dagger politicking, extreme mental and physical self-discipline, Bene Gesserit mind-reading premised on a kind of philosophical behaviourism, Ixian machinery that flirted with the ban on advanced technology, Tleilaxu cloning and gene splicing, and many other strange concepts and "big" themes. All set in a world where shareholder democracy and neo-feudalism have driven capitalism to its logical end point: a ritualistic obsession with buying shares in a single, all-encompassing corporation, the Combine Honnete Ober Advancer Mercantiles (CHOAM).

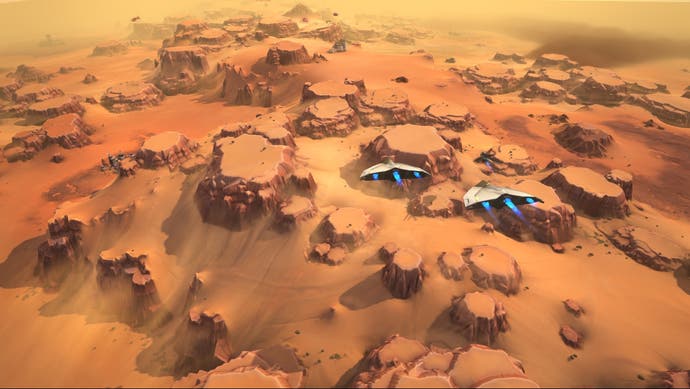

Heady stuff. To its credit, Spice Wars attempts to reflect many of these ideas. Each game starts with a base and an ornithopter, Dune's primary air unit. Send the ornithopter out to scour the fog of war - its dragonfly-like wings kicking up sand to the gentle synths of Spice Wars' excellent soundtrack - and find a richly detailed and surprisingly varied desert landscape, full of settlements, explorable points of interest, landmarks, and unusual topography. Build a couple of military units, annex a village, set up Spice production, and you are off.

Spice can be converted to Solari, the main currency alongside water, plascrete for construction, and fuel cells for advanced manufacture, but it must also be stockpiled to pay the Spacing Guild's taxes if you want to avoid penalties. Every time a tax is due, a new set of CHOAM shares is released, which can be bought to eventually secure an economic victory, but share prices fluctuate and the release of new shares erodes your stake.

The Landsraad meets regularly to vote on three motions and charters, from labour rights to who should hold the Dune governorship - another possible path to victory - and you can generate political influence to bolster your position. If you prefer a subtler approach, assassination missions can eventually be launched in an attempt to quietly remove your opponents, but they can also be identified and counteracted.

A combination of land and air units, all of which can be fitted with different weapons and abilities for an additional fee, can be trained or hired to lead you to domination. The illegal use of atomic weapons, Muad'Dib's greatest war crime in the first novel, is a tempting option to tip the scales on a close battle, but it will cost all your standing with the Landsraad and incur heavy sanctions.

Annexation, certain choices, and special buildings generate Hegemony - a reflection of your growing influence that can also lead to victory, but one that requires a carefully managed economy to sustain. Randomly occurring events, sandstorms, raids, and renegades provide additional threats and opportunities. Meanwhile, the relatively frugal research tree - divided into economic, military, political, and expansion research - gradually unlocks new structures, units, and tactics.

It's a fairly traditional set of 4X victory conditions, in other words, wrapped around a series of cost-benefit systems that speak to the fundamentals of Herbert's lore. Additional wrinkles come from the six available factions. The Atreides focus on Landsraad standing, the Harkonnens on military might, Corrino on CHOAM majority, Fremen on exploitation of the desert, Smugglers on black market tactics, and House Ecaz on culture and leisure. Each faction also picks two councillors, like the rogue Bene Gesserit Mother Ramallo or the mentat (humans trained to replace advanced computers) Thufir Hawat, that grant additional bonuses and ease certain paths to victory.

This dizzying array of variables ensures there is always something to keep track of, but rarely feels overwhelming. Spice Wars takes place in real time rather than across turns, but with speed and pause toggles to control the pace at any time (in multiplayer, these can be controlled by the match host, agreed prior to a match, or removed altogether). However, it maintains the "one more turn" compulsion of more traditional 4X titles like Civilization or the Endless series.

Unfortunately, morish as they are, these elements struggle to convey the depth and strangeness of Herbert's world. They brush up against it, occasionally finding some purchase, like the choice-consequence interaction between the use of atomics and Landsraad standing, but few of the big ideas noted above are given room to develop, often feeling like Dune dressing for traditional strategy mechanics.

All six factions are canonical, but it is odd to see House Ecaz given such a large role when more interesting actors that are also more prominent across the series, like the Ixians and Tleilaxu, are only occasionally referenced in easy-to-miss flavour text. All the more so given that Ecaz only gets a passing mention in Herbert's work (more in the expanded Dune universe authored by his son and Kevin J. Anderson). Diplomacy between these factions comes down to clicking on a leader, adding and subtracting resources or treaty types until their acceptance bar swings into green, then waiting for the deal. The courtroom negotiations, lies, and browbeating that dominate so much of Herbert's Dune and especially the later novels are absent here. Not to mention that most deals involve randomly generated numbers rather than something that could resemble a proposal by a real emissary.

Landsraad votes can seem similarly irrational, with Houses passing laws that harm them as well as everyone else or refusing to vote through beneficial motions. It's difficult to imagine why anyone would decline Research Investments, for instance, which gives a 50 percent speed bump to economic developments with no penalties.

Research benefits can be equally difficult to reconcile with the lore. Why is the option to establish a Trade Agreement with another faction locked behind a research milestone, for example? It makes sense in the evolution-charting likes of Civilization, but it becomes a little harder to believe that a civilization living thousands of years in the future would need to research how to negotiate a trade arrangement.

Sandworms are a fast travel option for the Fremen faction, but exist mainly to gobble up any troops and vehicles careless enough to stay too long on the sand rather than rocky terrain. Their religious and cultural significance to the Fremen is lost, as is their ecological importance to the desert and the implications of terraforming. Spice Wars notes that the Fremen want to turn Arrakis green, but does not incorporate this idea into gameplay. Likewise, Ecaz' ability to convert a settlement into a garden resort feels more like a caricature than an examination of ecological change.

CHOAM shareholding milestones grant bonuses to Landsraad influence and military units, but have no wider effects, and result in some baffling behaviour from the point of view of canon. While hardly news to 4X veterans - Civilization's Nuclear Gandhi might well rival Muad'dib for ruthlessness - it is nonetheless odd to watch the enemy AI force the frugal, austere Fremen to obsessively buy up shares in a corporation.

Councillors are disappointingly underutilised. How exciting it would have been to send a Bene Gesserit councillor to gain the upper hand in a particularly thorny Landsraad vote or diplomatic negotiation by reading the likely disposition of the opponents, or a mentat to calculate the probable size of the enemy force. Instead, once selected for their bonuses, councillors sit passively in the UI.

That isn't to say there is no interesting or meaningful asymmetry. For example, while the Smugglers and the Great Houses must annex regions and build refineries there before sending out harvesters to gather Spice, the Fremen use roving caravans that can be deployed in territory they do not control. Nonetheless, factional differences often reduce to what can feel like abstract spreadsheet balancing.

Indeed, abstraction is Spice Wars' overarching weakness. With one cutscene, no story, and minimal flavour text, a lot of what you do feels weightless and devoid of drama. This can be mitigated slightly by the type of game you play. Spice Wars offers three game modes. Battle for Arrakis accommodates up to four factions on different sized maps, while Kanly Duel pits two factions against each other in a tiny space for a quicker game. That intimacy lends itself to some genuinely thrilling action that can distract from the lack of authored drama - an intense back-and-forth over a Spice-rich region, a budget dwindling in the face of mounting military costs, and an assassination attempt foiled at 95 percent completion made for one especially tense and memorable evening.

But the distraction is fleeting. The third game mode, Conquest, attempts to tie individual games into a large overarching campaign, with significant gameplay modifiers and specific objectives for each mission, such as running an economy based on producing and selling fuel cells rather than Spice. However, without a fully-fledged narrative in the vein of something like Endless Legend, which found a way to balance 4X gameplay with faction-specific stories, this does little to alleviate the sense of distance from the action.

The fact that Conquest takes place on a tabletop map of Dune, carved into regions that the player can choose to invade, comes with an especially painful pang of nostalgia. This is, after all, precisely how Westwood Studios' seminal Dune 2, and its sequels Dune 2000 and Emperor: Battle for Dune, presented their missions. Unlike Spice Wars, however, Dune 2000 and Emperor came with those full-sized narratives and Westwood's trademark FMV cutscenes that, for all their cheesiness, did wonders to lend those games a strong sense of world-building and lean into elements of Herbert's lore that could not be adequately represented in gameplay.

It's a shame then that Dune: Spice Wars has opted for breadth of systems, rather than thematic depth. One can put labels like "Kwisatz Haderach" or "Fedaykin" on things, but without character arcs or mechanics that really demonstrate their significance in Herbert's universe, too often it feels like you're simply watching a +10 percent advantage in one area trade off against a -10 percent penalty elsewhere. Although there is no official mod support currently planned, the promise of further updates might alleviate some of these concerns. As it stands, however, Spice Was is an enjoyable enough way to spend the occasional evening, but it doesn't capture the longevity or unique appeal of its source material.