Dungeon Keeper, War for the Overworld and a helpful developer from EA

"No, sorry. He has a non-compete clause in his contract."

When EA got in touch with rambunctious actor Richard Ridings about reprising his role as Horny, the devilish mentor of Dungeon Keeper - that most treasured of cult classic video games - his agent dug up a surprising response:

"No, sorry. He has a non-compete clause in his contract."

What non-compete clause? What contract? It had to do with War for the Overworld, another video game Ridings had worked on, his agent said.

War for the Overworld is described as the spiritual successor to Dungeon Keeper. It's the game fans of Bullfrog's original dungeon management series have craved for 15 long years as EA left the franchise dead and buried. Its developers, collectively known as Subterranean Games, are a disparate but enthusiastic bunch, all the most passionate fans of Dungeon Keeper you're ever likely to meet. In fact it was out of this passion that War for the Overworld was born.

I remember covering the Kickstarter for the game back in 2012. Then the project was a team of around 15 professionals, modders and enthusiasts with big ideas and a Unity game engine license. They were led by lead designer Josh Bishop, a 20-year-old computer science student from Brighton, who spoke well about his favourite game and what he hoped to achieve with War for the Overworld. Peter Molyneux, creator of Dungeon Keeper, had endorsed the project.

In January 2013 the War for the Overworld Kickstarter ended with £211,371 pledged - over £60,000 more than the £150,000 target. While the Kickstarter drive fell short of the £225,000 required to secure narration by Richard Ridings, who lent his booming vocal talents to War for the Overworld's promotional video free of charge, Subterranean Games still accepted donations through PayPal. This extra money secured Ridings' work on the game, and, as a result, he signed a contract.

Of course there was no non-compete clause in the contract, no stipulation that Ridings could not work on some other video game. And back then, EA's ill-fated bid to relaunch Dungeon Keeper on mobile devices hadn't even been announced. What foresight Bishop and co would have had to display to have seen that one coming.

So, what was Risings' agent playing at?

"I don't know," Bishop tells me in a booth upstairs at a noisy EGX 2014. "He has a new agent now. We sorted that out. But it was a bit weird."

During the War for the Overworld Kickstarter someone from EA Mythic got in touch with Bishop requesting a Skype call. It was a call Bishop had expected, at some point, but he was nervous all the same.

"I had heard on the grapevine that EA might be doing something Dungeon Keeper," he recalls, "after we'd started our Kickstarter, anyway." Bishop handed over his Skype details, and the mysterious EA Mythic person video called. "I was like, er... I didn't really know what to think."

The person on the other end of the video call was Paul Barnett, an English designer who was then an executive at Mythic. Barnett, you'll remember, played a key role in EA's now closed massively multiplayer online role-playing game Warhammer Online.

According to Bishop, Barnett lifted an iPad up to the screen to reveal a new Dungeon Keeper game. "I was like, okay, interesting. I was relieved in a way, because I was like, that's not competition for us. That's a different market. That's a mobile game. And they were coming to us and showing us. It was this guy. It was a developer. It wasn't a suit with a briefcase. It was nice and incredibly unexpected from someone like EA to do that.

"He wanted to make sure we were a team of people who were passionate about the game and that we weren't backed by some big, other publisher. He also wanted to tell us what we should and shouldn't do as far as taking elements from Dungeon Keeper, which we were following already: don't use Horny, for example, because that was a character they had invented.

"That was all fine. He was very friendly. We continued to have chats after that. It was all surprisingly nice."

Following that initial conversation, Bishop knew EA was working on a brand new Dungeon Keeper game. He didn't know, however, that the new mobile game would end up riddled with in-app purchases shoehorned into the established and much-loved Dungeon Keeper gameplay in such a way as to render it almost soul destroying for any veteran fan of the series. As far as he was concerned, Dungeon Keeper was the competition. Potentially stiff competition.

"At that point all I saw was Dungeon Keeper mechanics running on an iPad," Bishop says. "I didn't actually see much gameplay. It was a mobile version of Dungeon Keeper."

Then, of course, the truth of EA's reinvention of Dungeon Keeper began to emerge. In August 2013 EA and Mythic announced a "twisted take" on Dungeon Keeper for Android and iOS devices. In October it soft-launched before releasing proper in December.

"It wasn't until a month or two before the mobile release, after it had been announced and there were screenshots and people had already been upset about it, that I had an early build to play with," Bishop says. "At that point I was like, it's an okay game but it's not what our audience is after.

"Look how many people play and enjoy Clash of Clans. There is an audience for that. It's just not us."

As far as Subterranean Games was concerned, at no point had it done anything that might get it into trouble. War for the Overworld was, clearly, inspired by Dungeon Keeper, but hadn't used characters from the franchise, lifted environments or copied art. It is of the same genre but avoids trespassing on EA's turf. And, if it wasn't obvious before, after the new Dungeon Keeper launched the two games were evidently worlds apart.

But I can't help wonder whether the young, inexperienced developers behind War for the Overworld were worried about a gargantuan publisher effectively slamming the banhammer down on the game they had worked so hard to get funded. You'd forgive them for being scared that War for the Overworld might catch the eye of the expensive lawyers at EA. I mean, all those "spiritual successor to Dungeon Keeper" headlines can't have helped.

Bishop comes across as a remarkably level-headed character, self-assured and quietly confident in his game and his ability to realise its ambition. If he was worried about EA obliterating War for the Overworld, I can't imagine he showed it.

"Not after the first phone call we had," he says, plainly. "Before then it was a big question mark. When the project was a hobbyist thing, we had sent them letters and whatever, and it had always just hit a corporate wall. It was like, yes, if you give us a million dollars you can have the IP or whatever. Silly stuff. Just generic responses. Nothing helpful in any way.

"But after that we were pretty happy."

Bishop, through Barnett, had a human being he could talk to about the situation. No threatening emails packed with legalese to deal with, no cease and desists to stress about. An actual human being on the end of the phone, who, I get the impression, was genuine in his attempt to help War for the Overworld succeed.

That's no guarantee, of course. "What else could we ask for, beyond a letter that says, yes, we won't do it?" Bishop wonders, now. "Obviously they wouldn't be able to give that." But it was a lot better than nothing.

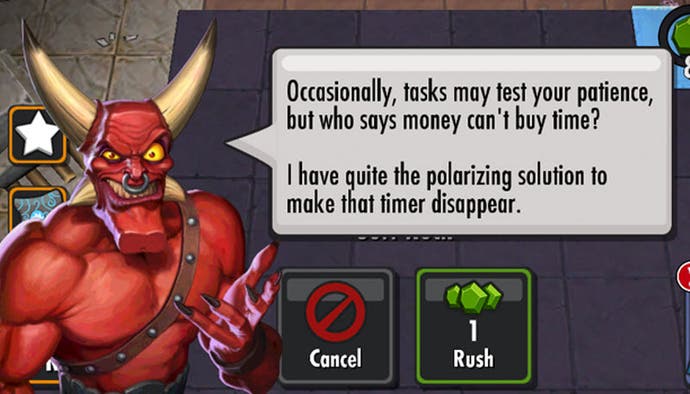

And at the end of the day, the outcry over EA's re-imagined Dungeon Keeper - which EA boss Andrew Wilson has admitted to me was "misjudged" - helped War for the Overworld. It shone a light on a once dormant genre, exposing Dungeon Keeper once again to a mainstream audience. Those core fans who played it in the hope that their childhood memories, perhaps, would be rekindled, left with a bad taste in their mouths. And maybe, just maybe, they found themselves hungry for a palate-cleansing alternative free from the corrupting influence of a "freemium" business model and "micro-transactions".

Enter War for the Overworld, which had emerged unscathed from its brush with EA over that most treasured genre: the dungeon management sim.

"It didn't help in terms of telling us what not to do, but it did help in raising the awareness of the genre as a whole," Bishop says, "definitely it helped in that regard."

"We'd like to think we already knew what not to do," Australian lead programmer Scott Richmond says. "We didn't need an example. But it did help bring the dungeon management genre to the fore."

Subterranean even promoted Dungeon Keeper when it released, mentioning it on their website. "We try to be unbiased as possible," Richmond says. "We let our fans know that was there and they could make their own decision about how they felt about that game."

Funnily enough, following the launch of War for the Overworld on Steam and Dungeon Keeper on mobiles, their developers followed two very different paths through the dense and dangerous jungle of video game development. Subterranean Games is holding fast off the back of War for the Overworld's success as an Early Access title. 15 people are working on completing the release version of the game, planned for February 2015. By then its modest but loyal community will have grown ever larger. There will even be a physical version sold in shops.

Mythic, on the other hand, is dead. EA shut it down half a year after the release of Dungeon Keeper. "That was a bit of a shock," Bishop remembers. "I spoke to this guy about four or five days before that and then... I don't know."

Fate, it seems, is a fan of irony. A developer of the new Dungeon Keeper helped the developer of the series' spiritual successor avoid getting into the kind of trouble that usually results in a cease and desist popping through the letterbox. Then the new Dungeon Keeper sparked outrage because it wasn't the kind of game its spiritual successor promises to be. One developer is still here, sitting on a successful game. The other is no more.

"I would characterise it as a massive learning experience," Richmond says, thinking back on the ups and downs of the past year.

"It's been amazing. This is our first big game or first game in general. We've had bumps along the way. We've had a couple of scratches here and there that left a couple of scars, but we're still standing, so that's really good.

"I've always dreamt about making games, and we've been doing it for two years, which has been great, but having that thought of walking into the local game store and seeing your box on the shelf, that's awesome. I cannot wait for that to happen."

And amid development, a moment's drama with Richard Ridings' agent. Barnett phoned Bishop and asked, did you make him sign a non-compete?

"It was funny that we were blocking them on something for a little while," Richmond says.

Bishop adds with a smirk: "I think that would have got us in trouble."