Eugene Peyton Jarvis - Pioneer

The creator of Defender and Robotron has been honoured by the AIAS - and it's about time.

When our sun explodes, I hope Robotron: 2084 survives. I'd lose Moby Dick, Angkor Wat, and The Well-Tempered Clavier to the flames if I absolutely had to, but I'd like to see Robotron, its cabinet sleek and its dark screen inscrutable, flung deep into the cosmos on a lonely spar of rock, so that alien life can one day plug it in and play it and know what terrible people we were.

The Mona Lisa, Hamlet, the Epic of Gilgamesh? These would only tell the rest of the universe what we were like. They are pale fire, ghosts of what we want to be or what we fear we may have somehow become. Robotron, though? Robotron shows its audience the truth. Its cruelty and its elegance reveal a furious species in love with beauty and with violence. We are babbling with toxic madness and clearly best avoided, and yet! And yet we are so much fun. Outer space will be safer without us, but it will be chillier, too. It will need Robotron to keep it warm. Robotron and a handful of quarters, obviously, because, man, that thing is a greedy pig when it comes to money.

All of which is worth reflecting on this week because Eugene Jarvis, one half of the two-man team that designed Robotron (his collaborator was Larry DeMar), has been honoured with a Pioneer Award from the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences. I stood up from my chair when I read that. My heart was lifted by the news and I whooped and the postman heard me and then hurried off looking a little frightened. So be it. Jarvis counts the likes of Ed "Asteroids" Logg and David "Pitfall" Crane amongst his fellow pioneers. They're gaming greats by any yardstick, but I think Jarvis outshines them. He's my favourite game designer of all time. He's the best.

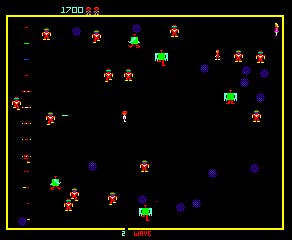

And, inevitably, his games speak for themselves: Robotron, the purest action title imaginable, which finds such glorious order buried within chaos, offering screens filled with enemies who move like bacteria as their conflicting agendas create near-endless replayability. Defender before it, which traded the cold clockwork of Space Invaders for the glorious feints and sleights of unpredictable AI - and simultaneously managed to break free of the confines of a single screen.

Blaster is, to my mind, a fascinating example of what happens when imagination outpaces technology - a Doctor Who time tunnel that threw 2D wave design into an approximation of three dimensions - while, beyond the dazzle of their graphics, Narc and Smash TV blended John Carpenter splatter with a kind of garish Verhoeven-like satire, cementing Jarvis' reputation as a man whose games actually had something to say about the era that created them. Look! We're one step away from killing people for free toasters, they whispered over the gunfire and the poisonous wretching of Mutoid-Man. An inch to the right and the streets will be filled with wild dogs as the cops wield bazookas in the name of freedom.

With early titles like these, Jarvis changed video games forever. The first arcade releases were often relentless, but he made them wild too. With Larry DeMar, he unshackled their enemies from their patterns, their unthinking ranks and their phalanxes, and scattered them across the battlefield. He allowed you to feel like a hero when you played because he forced you to improvise. Each game became a dialogue - a shouting match - between the player and the hardware. Each quarter you put in the slot provided you with a memory.

I got into writing about games because of Jarvis - Robotron wasn't the first game I loved as a child, but it was definitely the first game I loved as an adult, and I haven't been able to look away since. I first interviewed him for a magazine article on the making of Narc. I asked for 10 minutes and we spoke for three hours - and for all that time my heart was racing. Jarvis was everything I wanted him to be: thoughtful, generous, quick-witted, hilarious and clearly very brilliant. At one point he said to me, "Oh, you know I think about doing a Robotron sequel all the time," and I had to put the phone down for a second because I thought I was going to throw up with excitement. I've concocted various, inevitably rather tenuous, reasons to interview him in the years since then and, with great patience, he continues to deliver, whether he's reminiscing about the World War 2 factory building he worked in when he built Defender, or the weird cigar shop (and neighborhood criminal hangout) where he saw his first pinball game as a kid.

Beyond the games - and it's notable enough that Jarvis is known for not one but a handful of genuinely classic titles - and beyond the humour and cruelty he managed to bring to games when they needed it the most in their formative years, Jarvis is a rare example of an engineer who was also at home with mechanics. Emerging from the wires and buzzers of the pinball scene, he was a prototype for the modern idea of the professional video game designer, in fact - a role that hadn't really existed until the golden years of the arcades because of flukery and one-hit wonders and a quiet lack of seriousness regarding games' prospects as an art form. He's also stayed with arcades through the whole sweep of the medium's history: via Raw Thrills, the company he co-founded in 2001, he's still involved in the world of attract screens and penny victories today.

So congratulations on the Pioneer Award, Eugene Peyton Jarvis, and thank you for some incredible video games. Thank you for making video games incredible, in fact - and thanks for showing the rest of the universe what terrible people us humans are.