Eurogamer Q&A: Gaming's Greatest Monsters

Top Trumps.

'Monster' is a flexible term. It can of course be used literally, to mean some sort of hideous otherworldly creature - the kind which appears often in video games.

Every so often though, the term can be stretched out and draped over another human being, someone so decidedly evil that no other word will fit.

We see a lot of those types of monsters in games too - Bioshock's Andrew Ryan is a great example; driven by greed and corruption, he built walls between himself and the people he saw as "parasites" profiting from the work of the elite.

Games and villains, then, go together hand in hand. It makes sense - the conceit of beating the bad guy and saving the world is video games' most attractive proposition. But which games do it best? I asked my colleagues here at EG:

Wesley Yin-Poole, Deputy Editor

M Bison

M. Bison - or Dictator if you're big into your fighting games and want to sound all clever and stuff - is my favourite video game villain. My first experience of the overpowered leader of Shadaloo was running up against him in the SNES version of Street Fighter 2. The game's final boss was, well, he was just unfair. I didn't realise it at the time, but M. Bison in Street Fighter 2 cheated all over the shop. He could throw you seemingly from halfway across the screen, react to your moves before you even performed them, and did so much damage you'd dizzy from a kick or two to the head. I spent hours trying to beat M. Bison in that game. Hours and hours and hours. What a prick.

But I love and hate M. Bison in equal measure. He's always been a fun, unique character to use in the Street Fighter games, and, well, he's just got a lot going for him. His Psycho power gives his moves a maniacal edge, he looks down at his opponents and even laughs at their pathetic martial arts moves. And I love that he spends most of his time arms folded, even in a match, so unconcerned is he by his hapless foe.

Best of all, though, M. Bison has inspired some truly fantastic pop culture moments. Who can forget Raúl Juliá's wonderfully over-the-top portrayal of the mad dictator in the 1994 Street Fighter movie? (“For you, the day Bison graced your village was the most important day of your life. But for me, it was Tuesday.”)

Bison's star turn in the terrible Street Fighter cartoon sparked the "This is DELICIOUS!" meme.

And, improbably, M. Bison is a fashion icon. Don't believe me? Just ask Cheryl Cole.

Alex Battaglia, Digital Foundry

Gaunter O'Dimm

To be "careful what you wish for…" is a platitude often played out with a happy ending - It's a Wonderful Life comes to mind - but its inverted usage and personification through the villain of Gaunter O'Dimm in The Witcher 3's Hearts of Stone is one that has stuck with me long after playing. Gaunter O'Dimm, Master Mirror or the Man of Glass as he is also known, is a character who first harmlessly interacts with Geralt in the game's opening, giving you a tip for a quest line and then disappearing. I had already long forgotten him when he showed up later after the start of the Hearts of Stone quest. Here he offers Geralt a magical way out of a tight situation in return for a series of services to be rendered. As Geralt, you then follow the thread of consequences that Gaunter O'Dimm's genie-like wishes have brought upon the character of Olgierd to fulfil your end of the bargain.

There are many surface-level characteristics that highlight Gaunter O'Dimm's creepy and malevolent nature: how he stalks Geralt, hovering at the edge of many of the game's cinematic sequences; how he is capable of a casual and vindictive violence which comes to a head in a moment of squirm-inducing body horror. But I think the character's status as a great villain is cemented in the slower-burning elements in Hearts of Stone's narrative.

Without revealing too much, the fallout from Olgierd's wishes as granted by Gaunter O'Dimm slowly change his relationship with his much-loved wife, Iris. You are granted a partial view into day-to-day interactions that made up Olgierd's and Iris' marriage. You watch their love and relationship tested to the point of unravelling. This is all communicated in the grounded way you can expect of The Witcher 3's writing while being rendered in a visually arresting way. Take away the pretty pixels and the trappings of medieval dark fantasy, and you are looking at how many real world relationships probably come to an end - through misunderstandings and miscommunication. To know that such long-term, relatable, yet mundane misery is the design of Gaunter O'Dimm? Now that is evil.

Jamie Wallace, Commerce Editor

Tom Nook

At the start of every Animal Crossing game, you're introduced to the one townsperson who will go on to have the biggest and most negative impact on your character through the entire game. Stepping into your brand new hometown, you'll almost immediately run into Tom Nook, a seemingly-friendly racoon who seems to know his way around town and even offers to set you up with a house.

Your character, without a roof over their head or any possessions to their name, accepts the offer and from that point on, you're hopelessly indebted to his ever-increasing real estate empire. Simply put, Nook is the loan shark of Animal Crossing and you will spend the rest of the game paying him back, doing part-time jobs in lieu of payment or simply trying to avoid eye contact with him.

Nook's villainy is insidious. Animal Crossing is a series that is designed to be a safe haven - you can tend to a garden, you can decorate your home, you can fish. The world is, for the most part, peaceful, but for the ever-present Sword of Damocles that is the money you owe Nook. You will likely never escape from Nook, despite your best efforts - even if you do manage to pay his initial investment back, he forces you into a home upgrade, complete with a brand new set of debt to go with it.

Look past Tom Nook's argyle sweater and take a good look into his cold, dead eyes. Tom Nook is a crook that will gladly shake your hand, smile and affect on a warm exterior, all the while gouging you for money. This quite possibly makes him the most realistic video game villain to date.

Christian Donlan, Associate Editor

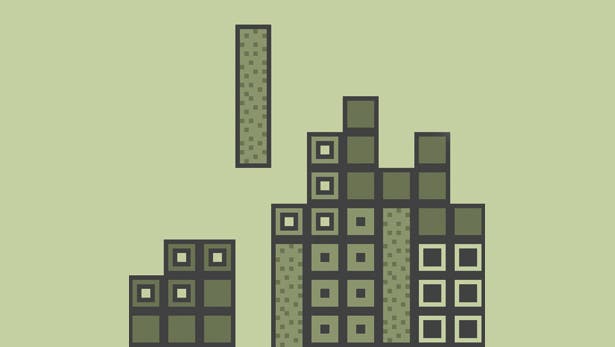

The Long Block in Tetris

The long block in Tetris is the greatest villain in video games, but I'm not surprised that nobody ever really talks about this. The long block is a villain in the Ben Linus style: you can never tell whether it truly means you good or ill, and the reason you can't is because you're being manipulated and toyed with from the very start.

The long block wants you to play a simple game in a complicated manner. It wants you to take unnecessary risks that often have devastating consequences. Sure, it says, you could play Tetris by clearing one line at a time, but is that really playing? Is that really living? What you might want to do is clear four blocks at a time - and to do that, guess what you're going to need?

The long block therefore makes itself indispensable, and it leads you awry with dreams and hopes of your own greatness. There is no greater kind of villainy, I think, that the villainy of someone who uses your own weaknesses against you

Emma Kent, Reporter Intern

GlaDOS

There's an old adage that you should keep your friends close and your enemies closer, which is just as well, because in Portal the only person (or thing) you had to guide you through the labs was GLaDOS.

In the first few levels of Portal, GLaDos seemed like a fairly normal AI system. A little on the sassy side perhaps, but her humour was amusing and made for great commentary as you bounced and bumbled your way through the tests. Soon, however, some sinister comments began to sneak out.

"Did you know you can donate one or all of your vital organs to the Aperture Science Self-Esteem Fund for Girls? It's true!"

Simultaneously hilarious and malicious, the remarks became increasingly malevolent until the realisation dawned that GLaDOS was really, truly, out to get you. The game then became a matter of seeking her out; an adrenaline-fuelled race into the depths of Aperture Science. The boss battle, when it came, felt incredibly epic due to the strange relationship between the player and GLaDOS built over the course of the game. Having been on such an intense journey with GLaDOS, I almost didn't want to kill her. I guess she could be described as a frenemy?

In any case, GLaDOS's incredible personality brought excitement to the game, and really formed the heart of Portal. Her savagery provided motivation for players to do better in the tasks, and look to progress in what was otherwise a (deliberately) sanitised world. Even once I'd finished Portal, I found that the memory of GLaDOS's sarcastic voice lingered in my head. I still aspire to reach her level of sassiness.

Oli Welsh, Editor

Majora's Mask

Forget Ganondorf, or Calamity Ganon or whatever form the Legend of Zelda's traditional villain has decided to take. I like his red sideburns and I enjoyed the fencing battle with him at the end of The Wind Waker, but at the end of the day he is just another Video Game Bad Guy, out for power, who seldom supplies the series with its most memorable moments. In Ocarina of Time, it is the confrontations with illusory doppelgängers that linger in the mind instead: Phantom Ganon, riding his spectral horse out of the paintings on the wall, or Dark Link, the player's malevolent mirror.

In Zelda, it's usually not the huge monsters or the scheming villains that really chill you. It's the ghosts, the voids, the forces of nothingness that smother life. It's the inky fingers of Wallmaster reaching out and sucking you into the stonework. It's the petrifying cry and the cold, crushing embrace of the ReDead. Fitting, then, that in the series' most troubling episode, Majora's Mask, the ultimate antagonist should be a haunted mask that feeds on the bitter loneliness of its wearer - an impish outcast called the Skull Kid - and seeks only oblivion for everyone and everything by crashing the moon into the world.

Majora's Mask isn't a horrible creature or a flamboyant evildoer, it's just a thing: a thing that channels the nihilism and rage within its wearer, within us all. That's why it's so scary. (Well, that and those staring eyes.)