Exploring Falmouth and the naval history behind Return of the Obra Dinn

Sail on.

This piece contains spoilers for Return of the Obra Dinn.

Waves lap gently against the struts of the pier as seagulls wheel, dive, and caw overhead. Halyards on anchored sailboats gently clink in time with the movements of the water. A gentle rumble emanates from the engines of the docked Merchant Navy vessels, underscoring the whole scene.

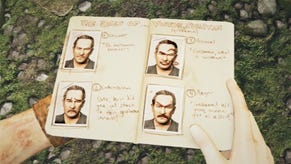

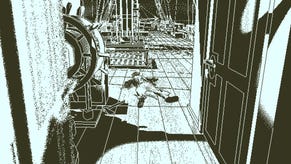

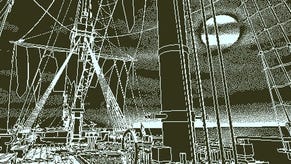

This is the harbour of Falmouth as it exists today. Situated at the mouth of the River Fal it remains a busy and important shipping hub for England's South West corner. Looking out from the pier towards the docks on a drizzly Saturday morning it's not hard to imagine the haunted corpse of a single ghost ship slowly drifting in to port. This is how Return of the Obra Dinn begins, the titular ship borne into the bay with damaged sails and a slaughtered crew. The player is hired by the East India Company to investigate the grizzly fate of the ship's crew and find out just how this came to pass.

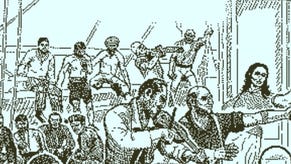

Set as it is during the early 1800's, Return of the Obra Dinn presents with us a period of naval history rife with intrigue and spectacle. Cornwall and Falmouth in particular fast became a hub for the activities of the British navy and the East India Company. Falmouth was an integral part of the Post Office's Packet Service from around 1690 onward. From it, packet ships were dispatched to all over the British Empire delivering important messages. This often involved running from privateer ships or those of Britain's enemies, who were numerous in this period given the British's love for going to war with just about anyone.

Philip Marsden's book The Levelling Sea gives a vivid account of Falmouth's rise as a port town and the lives of its inhabitants. In one chapter he recounts the lives of some of those who sailed on packet ships. One sailor, a Michael Kelly, has his ship captured by American Privateers. Rather than surrender with the rest of the crew Michael hides away, only to emerge to then help the privateers man the ship. In an almost farcical turn of events he and his original captors are in turn captured by a different English crew. The perils of sailors such as Michael Kelly cast the setting of Return of the Obra Dinn in a fresh light. The cargo the Obra Dinn carried was just as valuable as any confidential orders, even more so given its mystical properties.

It's little wonder then that real life ships carrying treasures not even close to the value of that carried by the Obra Dinn were a common target for 'wrecking'. This would involve luring a ship into rocky waters where it would 'wreck', its innards spilling out onto beaches around the Cornish coast to be picked clean by the residents. Whilst the crew of the Obra Dinn do not fall prey to this particular practice, its regular occurrence along the Cornish coast gives context to other real world ships that would have disappeared at this time.

Cathryn Pearce's book Cornish Wrecking: Reality and Popular Myth delves into the subject at length and details how everyone from fishermen to local clergy took part in the practice. 'Wrecking' as Pearce details it covered a range of activities from hauling bags of washed-ashore coffee up sheer cliff faces, to deliberately cutting a ship's cables to drive them towards more hazardous waters. Whilst violence towards the crew of the ships was actually quite rare, this didn't stop the wreckers from perpetuating that image. Members of the East Indian Company took letters to the Houses of Parliament in 1708 that described how Cornwall's "savage inhabitants are ready to plunder what they have gott & cutt their throats too".

It is however not the acts of humans alone that cause ships to disappear and crew to be brutally murdered. There are beasts beyond the comprehension of man, unseen forces that lurk in the deep. Such creatures inspired superstitions and rituals practiced by sailors of all nations, and the Cornish people were no exception. Some believed that whistling summoned the spirit of a vindictive wind, a crime which many women were hanged as witches for, whilst others maintained that cats running wild through a house brought storms on their tails. For anyone who has ever owned a cat the latter sounds quite plausible.

Return of the Obra Dinn gives further insight into Cornish mythology through its inclusion of one creature in particular: mermaids. In the game mermaids are seen as both an aggressive and friendly force that at first attack the ship and eventually help it to return to port. In Cornish mythology the creatures are more often portrayed as the latter, a fact that provides an insight into the Cornish's tempestuous and romantic relationship with the sea itself.

On the side of romance we have the tale of the Mermaid of Zennor in which one of the creatures emerges from the ocean to seduce the local church's star singer. A wooden portrait of the mermaid hewn into the side of one of the church's pews stands as testament to this. The Mermaid of Padstow on the other hand has a somewhat more violent ending. This mermaid is noted as being responsible for the sandbar that now lies across the town's bay after having been shot by a local man whose marriage proposal she refused. The 'Doombar' as it is now known is where the popular ale gets its name from.

Another mythical creature that makes an appearance in Return of the Obra Dinn is the Kraken. Whilst this mythical cephalopod has been depicted in all manner of works from a sonnet by Alfred Tennyson (The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee) to Marvel's Wolverine comics, it never seems to have made the journey to the the south coast of Cornwall. We are instead graced with sightings of Morgwar, an illusive sea serpent claimed to be of a similar size and nature to the Loch Ness Monster.

Tales of the Kraken are often used to account for the disappearance and destruction of many a ship lost at sea. Here it would seem that there are some similarities between the behaviour of the Kraken and the Mogwar. One of the most notable reported sightings of the Mogwar is from 1910 when it was spotted chasing away a German U-Boat after it attacked a British merchant vessel. Why the Mogwar was never called up as part of the ongoing war effort will forever remain a mystery.

In 1863 the first steam train pulled into Falmouth station, its whistle the death knell for the maritime packet service that had been fast declining since 1851. Set as it is in the very early 1800's, Return of the Obra Dinn represents the last century in which ships like it would regularly grace the waters around Falmouth. Steam power was king now. The demise of sail ships at this time gives Return of the Obra Dinn a note of futility, its crew having died for a trade that within 100 years would cease to exist.

Photographs courtesy of the author.