Exploring the afterlife of historical sites in video games

Model behaviour.

I've spent hours walking the halls of Volterra Asylum, and yet I've never actually visited it. The Town of Light contains a meticulous reconstruction of the Ospedale Psichiatrico di Volterra in Italy, inviting you to explore the asylum as well as interacting with documents and objects based on actual archive materials from the institution in order to relive the memories of fictional patient Renée. The Town of Light allows you to experience a heritage site with a difficult social history, an ostensibly pastoral centre which mistreated and even abused its patients. It's a kind of dark digital tourism experience.

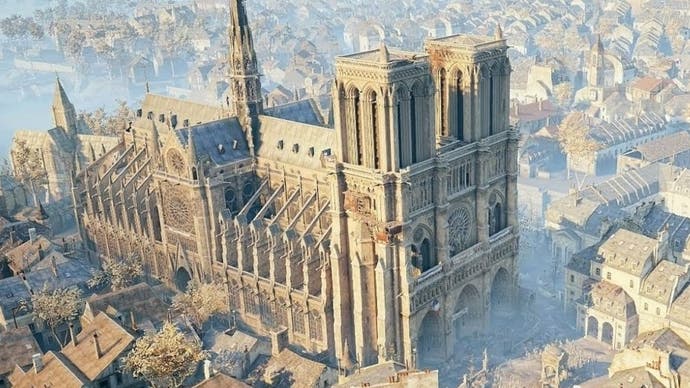

There has long been an interplay between video games and architecture, so when I heard them described as "cathedrals of the modern age" by Small Island Games' James Morgan at a recent event I was intrigued. I'm an archaeologist who loves video games, so any overlap between the two always excites, and Assassin's Creed Unity has received a lot of attention for its digital reconstruction of the recently damaged Notre Dame Cathedral. It raises the question of how and why we value certain pieces of human craft. Should a cathedral, or indeed a AAA game, be the benchmark of historical and contemporary craftsmanship?

Much has been said about Assassin's Creed Unity, but I'd like to focus on two other games, The Town of Light and Their Memory, that also constitute historical and archaeological sources in their own right. Luca Dalcò, Town's lead developer, confirmed that creating an historical record wasn't his main motivation in reconstructing the asylum. His initial focus was to "recreate the feel of the place." Luckily for Dalcò and his team, their office in Florence is close enough to Volterra (about 52km north-east of the town) that they could make frequent field trips to the asylum. Photogrammetry was not used to clone the buildings; instead they employed a patchwork of photographs as a reference when creating the building textures. The architecture you experience is made up of records taken over several visits in different conditions - an exact replica is of course impossible.

Whilst it's easy to fall into the trap of just focusing on making a game environment as photorealistic as possible, the use of music and audio effects is just as important. Given that The Town of Light could be described as a walking simulator, it's apt that Dalcò referred to sound and visuals as being "the left and the right leg for a walker." Games may try to put their best foot forward with lush, aesthetically pleasing landscapes, but a carefully composed soundtrack can evoke atmosphere that would be impossible to capture visually.

On this note, it seems fitting to mention that oral records were the starting point for VR game Their Memory. "The initial concept was to take existing oral histories that can be languishing in museums, archives and library collections and put a modern spin on them," producer Iain Donald, Senior Lecturer in Game Production at Abertay University, explained to me in our email interview. He and developer Emma Houghton, who recently graduated from Abertay and is now a game designer at Rivet Games, digitally recreated the Lady Haig Poppy Factory in Edinburgh.

The VR experience allows you to explore the space, with the key mechanic being that when you pick up an object belonging to a veteran you hear a recording of them telling a personal anecdote. Houghton explained that the idea to base the game in the factory only came after they visited the building, "[b]ecause the factory was potentially being refurbished or demolished entirely I thought it would be interesting to take a snapshot of how it was since it would never look the same."

As was the case with The Town of Light, development involved numerous trips to the building to make photographic records, which was facilitated by a partnership with Poppyscotland. Houghton used Argos catalogues as a kind of contemporary archival reference for the interior furnishings. Creating a 1:1 model of the building was not possible for two reasons; firstly because the space actually felt wrong when Houghton blocked it out in virtual reality so she had to make it smaller, and secondly because there was just too much stuff! "There were challenges,' Donald tells me, "one veteran has collected lots of Minions paraphernalia and as much as that was part of his desk we couldn't create characters or content that potentially required licensing."

Pesky yellow gremlins aside, the personalities and experiences of Their Memory add an extra layer to the audio-visual record of the Lady Haig Poppy Factory. Though there were some concerns about data protection, each audio clip is spoken by a veteran. Focusing on civilian experience and aftercare is a powerful aspect of the game. "It wasn't just a place of work for them," says Houghton. "For some of the veterans the factory saved their life, for some it allowed them an environment in which they could talk about their experiences and their trauma with people who would understand." Donald and Houghton conducted some co-design sessions with local groups, and veterans tried a prototype of the game. Given there have been some concerns about the accessibility of VR, I was keen to find out how they had reacted to it. Houghton confirmed that none of the veterans had ever worn a VR headset before, "but they took to the experience surprisingly well."

Unlike the Lady Haig Poppy factory, Volterra asylum is derelict. It's possible that if the complex were to decay further or be demolished, The Town of Light would be the only way that a person could visit the buildings as they once were. Dalcò describes an incident in which a charity worker taking care of the area had made the same point to him and that he feels responsibility for the site as a result. It seems to me there is huge potential for video game developers to collaborate with historians and archaeologists, and Dalcò agrees. "The game industry could dramatically accelerate the process of digitalisation of historical and archaeological sites," he says. "But it's crucial to have as much support as possible." Whilst Ubisoft may have been able to donate €500,000 to the restoration of Notre Dame, indie studios might struggle to fund their own digital reconstructions in the first place.

Dalcò explained to me that the Legge Cinema law was passed in Italy in 2016 which establishes video games as potential cultural products that can be funded by the government, however in practise there are still no clear guidelines for how developers should apply for this money. The value of the digital doppelgangers in both The Town of Light and Their Memory, though, is priceless. This is not because they represent perfect architectural models, but because they capture the interpretations of their creators. As Donald himself puts it, "The photos that we took as reference material have now become their own archive of how the factory looked before refurbishment. That's really interesting from a historical perspective in that the project has been about using existing archive material - and in doing so has created a lot more archive material."

Let's circle back to the proposition made at the beginning of this piece, that large open-world games can be likened to cathedrals. If that's the case, will we mourn the loss of access to video games in the future the same way the world mourned Notre Dame? What sources and memories will we use to reconstruct a video game experience? Maybe one day there will be oral histories of The Legend of Zelda, Assassin's Creed and other vaulted titles of this video game generation. However, it's the smaller games and the local stories that they hold like rock pools on the coastline of history, that'll be the most difficult for me to forget.