Exploring the economics of suffering in This War of Mine

Scavengers assemble.

There are circumstances in which a bandage is worth more than a diamond. For example: any circumstance in which you happen to find yourself bleeding heavily. This War of Mine pretty much buries you in these kinds of circumstances. It's a survival game, and, for all its panic and blind grasping, it's also a game about economics. Wartime economics. Prison economics. Diamonds are down, and bandages are up - way up.

I was introduced to this collapse in the value of diamonds because I'd been asking 11 Bit Studios' senior writer Pawel Miechowski about the grotesque nature of war - or rather, about how it's the innate grotesqueness of war that comes through most vividly these days now that the stoical, stagey distance of newsreel men has been replaced with something a little more immediate.

"We found some very grotesque facts," Miechowski says. "We found the grotesque wherever we looked in our research. In Sarajevo, which is a very well-documented siege, vodka was the best tradeable item. That's the grotesque, right? They were using the vodka to clean wounds, to drink when they needed cheering up, and to trade for the supplies they needed to get by. Vodka and cigarettes. When the Second World War was over, the official currency of Germany was cigarettes. You trade items for items in war. There's no money any more."

This War of Mine is not so much a game about war as it is a game about war's shadow, in other words. There's a conflict going on, but it's been carefully decontextualised so that the focus is shifted from the political to the human, from victory to just getting by. You're not a soldier. As you play, you divide your time between a shelter, where you hole up when things are too deadly to go outside, and an expanding map that covers the remains of the city you're trapped in for as long as conflict rages. Movement between the two spaces is dictated by a day/night cycle, but the twist here - it's the grotesque, rearing its head again - is that you venture out at night when the snipers can't draw a bead on you. War is a place where everyday logic is turned on its head.

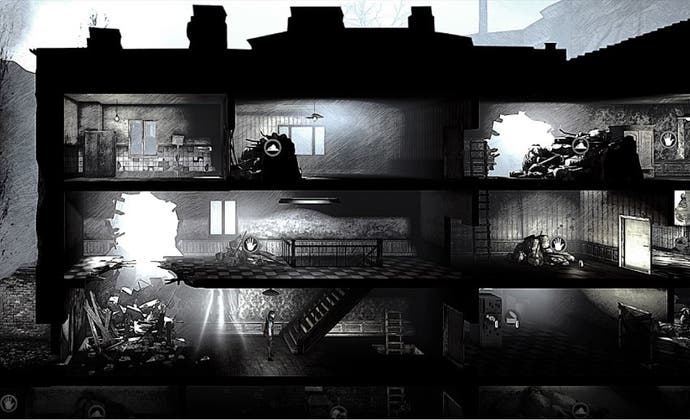

We found diamonds early on, Miechowski and I. At first glance, the game's shelter screen looks a little like an XCOM base - a doll's house cross-section of rooms and action figures, the latter of which are your handful of survivors. A closer look, though, is a little disorientating. Walls and ceilings are caved in, allowing sketchy beams of light through, while the rooms themselves are studded with interaction icons encouraging you to dig, to craft, to move your survivors around and get them doing something, anything. There's no tutorial here. "There's no tutorial in war," says Miechowski, and I take his word for it. It's surprisingly easy to fall into the game's rhythms anyway.

Those rhythms are initially pretty familiar, in fact: hunt through the rubble for resources, and craft the resource into things that you might need. Store medicine, bandages, weapons and food, and then start to think about second-tier items - a bed, which will stop people getting sick from sleeping on the floor, a heater "for when winter strikes", a radio for morale and for garbled news from the frontline.

Your shelter only offers finite resources, though: once you've scoured every inch of it, you will need to go out to get additional supplies. When night falls, Miechowski packs a bag and we set off for a nearby encampment. We've got a crowbar for protection, and we've got food to trade for medicine, as one of our three survivors is sick. Failing that, we can maybe win someone over and encourage them to join us: another pair of hands to help around the shelter, even if that means another mouth to feed.

As it happens, our first night out leaves us with one mouth less to worry about. The neighbouring shelter doesn't need food; at the doorway, we're told they're after medicine too. Miechowski decides that we'll have a look around anyway. If we can't trade, maybe we can steal something.

Our neighbours aren't keen on that, though, and in a few short, messy seconds, we've been shot dead. No restart, no revert to a save, just another dawn greeting the two men left in our shelter.

Morale's lower than ever, and morale matters here, since This War of Mine models the mental health of your survivors as well as their physical health. "This is not a simulator of atrocities," says Miechowski. "It's a game to show you how people struggle to survive." And sometimes, they really struggle. Low spirits will mean that tasks take longer, that medicine is less effective, and that your survivors may even refuse to do what you tell them to do as you direct them around with your pointing and clicking.

It's this aspect which is most fascinating, I think: the mood in the doll's house may get so poisonous that even the dolls start to find it oppressive. Even the dolls will start to revolt. Can you ever win? I ask Miechowski, and immediately feel stupid. He shrugs as we head out for another night-time excursion. This time the neighbour greets us holding a familiar-looking crowbar. Miechowski says something that I can't quite hear.

The really weird thing about my entire interview session regarding This War of Mine is that, listening back, I could barely hear any of it. There's nothing wrong with the recording, we just weren't speaking very loudly. I collected 42 minutes of hesitant muttering, in fact. As soon as Miechowski loaded up the current build, we both retreated to a tentative whisper. Miechowski was excited to show off his game, and I was excited to see it. We don't sound like that, however. We sound like wildlife journalists watching the camera feed from a fragile nest.

There are a number of reasons for this, and one of them is that This War of Mine is a game that has a kind of animal documentary wildness to it, even if the animals in question are humans. And, speaking of humans, the main reason for our murmuring is possibly what Martin Amis refers to as species shame. This War of Mine offers a simplified glimpse at what life looks like in some of the worst circumstances available - and as you pick through these circumstances, it's hard not to avoid the feeling that the whole thing doesn't seem very necessary. Why did it have to be like this? Why does it have to continue to be like this?

What do I do with all these diamonds?