Left 4 Dead

The best thing since sliced dead.

Playing as Infected is typically this way. It's part Alien vs. Predator, part Spy vs. Spy. You can usually see the survivors as red ghostly figures through the walls, helping you to stalk them, and the game also paints red arrows on the floor to show you their likely route, and highlights pipes you can climb and bits of destructible scenery. Your job is to cause as many hitpoints of damage as possible - that's your score. As the Smoker, you can lie in wait, and then use that prehensile tongue to actually hang someone from above. "It's terrifying as a player to have that happen," says Johnson. "There's nothing more fun in the game - I know Chet and I would say so anyway - than choking somebody to death as a Smoker." "And then choking the person that comes to help them," Faliszek points out. With up to four players on both sides, the AI director makes sure the survivors aren't too severely overwhelmed, managing your Infected spawns. Inevitably it's a bit street-smart about this, too, recognising that if you're a Boomer, for instance, and you die within two seconds of spawning, you probably deserve another go immediately.

There's tremendous potential to be sneaky and foster panic in the survivor ranks. A favourite tactic as a Hunter is to lay low as they approach the final section of the scenario, where the game gives them a breather. Wait for them to let their guard down, and then pounce. As a counterpoint though, cunning players like Valve's John Morello can hang back, go quiet and ambush predatory Infected. The hunted becoming the hunter. Staying off the Infected radar requires patience, as you need to slow to walking pace and switch off your flashlight to avoid showing up as a red man through the wall, but the pay-off for the industrious survivor is quite something. And of course this is a team-based first-person shooter, so you can see who you kill, and then yell something across the office.

Turning off the flashlight wasn't for me though, which is a clue to how much vision plays a role. All four scenarios are set at night, and even interior sections and the sunrise on a cornfield endgame don't lessen the need to keep yourself lit up. Fortunately the batteries in this light are a bit better than whatever Gordon's using in Episode One. It's still for nothing when a Smoker uses his ability to fog up a room, though, sewing panic. And while the flashlight can identify Hunters as they lurk, it also lights you up through the walls, and it certainly gets up the nose of the one Infected boss you can't play as, the Witch, who arrives on Normal difficulty and above. She's a bit like the Berserker from Gears of War's evil twin. Combating her is "not about being a super marksman," says Johnson; "it's about everyone agreeing what the plan is; if you're going to attack her or try to sneak by her, and hopefully everybody's sticking to it. It's one of those things where the price of failure's incredibly high."

The Witch is an enemy that demonstrates how Left 4 Dead's not about level-dominance in the way Counter-Strike was, but escape. Bolting to checkpoints, getting everyone inside and closing the door - probably using the right-click melee to barge Infected back from the narrowing gap. The checkpoint rooms are a welcome respite, providing ammo and sometimes health, and you can't rely on seclusion anywhere else: when the banging starts to ring out on a slim metal door I've sought refuge behind to reload, I notice it's starting to pepper with dents, and then a hole's ripped through. As I fire through it in alarm and then start jamming shells back into my auto-shotgun, the whole door gives way and the surge overwhelms me.

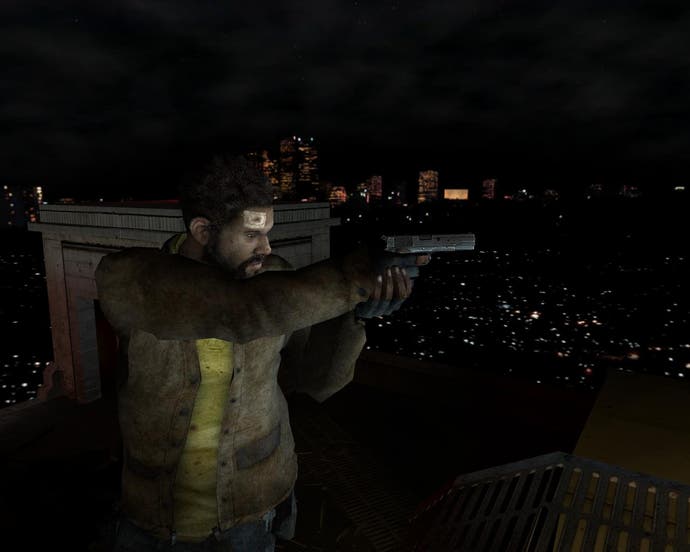

When I respawn, it's on the roof of Mercy hospital, where a helicopter is supposed to come and extract us. Before it does that though, there's the final fight. You're given time to prepare, scattering petrol canisters into key areas so that if things get hairy, you can loose a round into one and hopefully stem the flow of Infected. When you activate the radio signalling for help, the AI director cracks his knuckles behind the curtain and unleashes hell. Each scenario's endgame is slightly different. "They play out similarly but the terrain itself is such that they play out pretty differently," says Johnson. "The one where you're on a rooftop's tough because you can get yanked off by a Smoker, so instead of looking up you need to look down." He says the one set in the cornfields is probably the spookiest in terms of feel, as you arrive in the dawn-lit lanes of corn and quiet sweeps over the group.

The endgame is your last stand, after which the scenario ends, and it's brilliantly frantic, like the iconic scenes of a zombie film. But the Z-film genre's influence appears to be subtler at Valve than it has been in other survival-horrors like Resident Evil and Dead Rising. They don't rip off Bruce Campbell's one-liners (although characters do chime in, and some of it is pretty comic - especially the orgasmic healing sounds, which I hope they keep), but don't imagine it all had no influence. "The cornfield's a pretty good example. You use imagery in-game to evoke emotion in players one way or another, because it's a language that people who consume that kind of media understand," says Johnson. "We do it in Half-Life all the time to give people a feeling of oppression."

Oppressed is the right word for how you feel after a few minutes trying to survive, and the natural bond that always develops between survivors in Z-films is carefully assembled here. Into this, tactics flood naturally. It's not like Counter-Strike, where you're going to get shouted at for not grasping inobvious things like the need to run with the knife to maintain speed. Bottle-necking enemies, crouching if you're in front, keeping eyes outward, and cover-and-move all slip into your play, helped by some of the better elements of its cousin-game, like having sniper rounds go through thin wood, and a range of easy keyboard-comms accessed through Z, X and C. You can also vote for things, which is handy if you want to ban Doug Lombardi from using grenades - something that proves popular in Bellevue.

But, as we said last time, this isn't Counter-Strike, and it's not Half-Life either. It's something else. It's hard to pigeonhole. What it definitely is, is fun, whether it's the thrill of blowing a leg off an Infected and watching him hobble towards you for a couple of steps, the thrill of the hunt, or the realisation that experience is nothing: hop in an elevator and you might make it the whole way up the shaft without incident, only for a sodding Boomer to land on top of you the next time you board. It hits a lot of buttons, and game's composure is clearly far from accidental. Perhaps that's why they're allowing everyone to play with me in spite of looming deadlines: positively reinforcing good co-op development. Or perhaps, like me, they're just a bit in love with Left 4 Dead, and make time for it even when they shouldn't. If Valve can match the game to a system that makes it work well over the Internet, it could be very big.