Archer Maclean's Mercury

Rising to the top of the PSP agenda.

Awesome Studios' multi levelled back entrance appears to be designed to conform to Archer Maclean's penchant for innovative puzzles. Accessible via either the basement or first floor iron staircase, it's not immediately clear which the main entrance is. "Are you the journalist?" pipes one of the dev team, evidently noting my quizzical expression; he duly beckons me to the basement. But just as I'm about to slink into the gloom, another member appears at the top of the other entrance. "Come up this way," he insists as I blunder my way haphazardly around Awesome/Ignition's curious entrance system.

We have...

The man himself bounds on through, apologising for his late arrival: "Mercury's just gone Gold," Maclean confirms with a firm handshake, a sparkle in his eye despite last night's 2am rush to the finish line. Steaming cuppa in hand he notes my shiny new PSP, but regretfully informs me I won't be taking home a copy of Mercury just yet. "Currently test UMDs are only currently available from Japan, no one outside of Japan can create them," he admits. Bang goes my hope of showing off my PSP in style over Christmas.

With that in mind the trip to Banbury was both well timed and well worth it, given that I got to sample 14 of the game's 72 levels with expert advice and a one to one demonstration from the game's legendary creative director - a man clearly buzzing with the knowledge that his company has managed to overcome innumerable hurdles in getting such a project off the ground in this play-safe era of licensed me-too fodder, and one that looks set to deliver one of the most pure gaming experiences for many years.

Asking what I know about the game, I freely admit that I'd avoided reading Edge's recent six pager to forestall any preconceptions. "Best way to be," he nods, before starting from the top. "You know those little toys you had as a kid where you have to guide ball bearings into the holes? Mercury was basically inspired by that," he says, handing me three of them by way of demonstration. Clearly, though, Maclean's interest in puzzle games goes way back, via the numerous mini-games that populated Jimmy White's Cueball World.

One in particular featured four balls in a maze with four goals, the idea being to guide them to the appropriate exit. Noting that some critics focused more attention on the sub-games than the main simulation itself, Maclean began to realise that perhaps the time was right to explore the idea more fully, and gradually the notion of adapting the concept to Mercury was born.

Imported

But what was originally conceived as a PS2 game and shown off to Sony in November 2002 (six months before the PSP was even announced) eventually morphed into a PSP title at almost exactly the right moment for both parties. But even when Sony made the call that it was interested in the game being made for the PSP, Ignition was forced to spend the first half of the games evolution on its own cross platform engine. "The head of R&D, Jeb Mayers, was absolutely determined to make it work and basically said sod it to Christmas last year; in fact he's just gone home now to do some more programming!," Maclean laughs. "We were a bit worried at first because it was running at quite a low frame rate, but it was case of just optimising it, and it all came together in the end." In fact, given that PSP hardware has only been available for the last few months, it illustrates just how well the team has coped with the project's compressed development cycle.

There is a downside, however, with some of the scope of the project likely to be somewhat scaled down for the time being (ah, the glory of sequels), with the game's mooted tilt sensor add-on still not confirmed at the time of writing, as Maclean explains: "We really want to get the tilt sensor out for launch, but logistically it's going to be a nightmare". The decision rests with Sony, though, so it hasn't been ruled out entirely, but even if it doesn't make it, though, the plan is to make the game backwardly compatible if and when the peripheral sees the light of day. Having played the game with it, Sony would be mad not to back it all the way.

But having spent a decent chunk of time playing 14 of the 72 levels (less than the reported 108 - a decision which Maclean says was down to the need to get the game gold mastered by Christmas) using the default analogue stick it's fair to say it works brilliantly either way, with the tilt sensor unbelievably smooth and precise. But even with the analogue stick it was arguably equally precise and responsive - a comment that came as a relief to R&D chief Mayers: "We didn't want to design a game that relied on the tilt input," and thankfully I found no preference between the two - except the immense novelty value of using the PSP as a tilt sensor. But as Maclean pointed out later, there's more to the tilt sensor than may immediately be apparent. "It's subtle, and everyone misses this, but when you're using the tilt sensor the maze becomes fixed and the game behaves as if the mercury really is trapped beneath the screen. That's exaclty how we concieved it in the first place."

Therapy?

The game itself is simply one of the most pure gameplay experiences I've enjoyed all year. Asked for first impressions I felt strangely at ease. It felt therapeutic, as if I was engaging in some kind of advanced anti-stress device. Even when I messed up I knew the only person to blame was myself and my lack of skill. Admittedly I only sampled some of the less advanced levels (the 12 level long Training Camp which unlocks the 'proper' levels beyond) and with greater difficulty comes a greater sense of frustration, but the fundamentals behind Mercury are so refined that even at its most vicious the errors are all yours - not the game designers'. Or at least that's what we want to believe at this point. We await the finished article to see if that kind of claim holds any, um, Mercury.

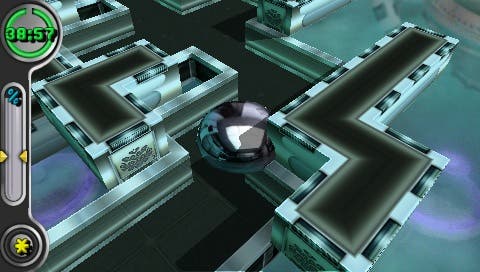

So what is this pure gaming experience we've gone all round the houses talking about? Essentially it's about guiding your blob of mercury to each level's goal. If you've played Marble Madness, Spindizzy, Bobby Bearing or more recently Super Monkey Ball you'll have a rough idea of what to expect. The key difference with Mercury is the thing you control - the blob, if you like. In all those other games you were controlling a solid unchanging spherical entity; this time you're guiding matter which can split into numerous smaller blobs (16 in total). Sometimes you need to guide all 100 per cent of the blob to the goal, sometimes you can get away with less, sometimes you need to divide up your blob deliberately, change the smaller blobs' colours, activate colour-coordinated switches and even rejoin your blobs to form another colour in order to then go on and activate that switch. It's the sort of brilliantly simple concept that's instantly playable and tests everything from your hand-eye co-ordination to your ability to think laterally. It's one of those rare beasts - a puzzle game that uses technology to inject something new into an otherwise incredibly simple concept. According to Maclean, the calculations required in rendering and calculating the blob's positioning take up to 90 per cent of the processing power of the PSP, giving some indication as to why this idea wouldn't have worked on older tech.

The game world itself is structured neatly around a hub-based system, with six areas each comprised of a tree of four lots of three game types; puzzle-based, a race against the clock, and those that require a minimum amount of your blob to reach the goal. Each world ends with its own 'boss' encounter and comes with its own flavour of baddies. During our brief encounters we were harassed by nasty 'Mercoids' which chase after you, forcing you into making hasty movments that could force you into other obstacles or off the course entirely. Let them catch up and they munch away your blob, so you're damned either way.

Steely

Being a puzzle game there's plenty of traps, door switches, spikes, zapping electrical fields, moving floorways and various other elements that help and hinder from sucking transportation pipes to sharp edges that allow you to subdivide your blob as appropriate. No doubt there's plenty more than that to talk about, but even in 45 minutes or so of actual hands-on we saw enough to fall in love with it immediately; the visuals are sharp, suitably metallic and stylishly in-keeping with the task at hand. It's often simple, regimented level design is never going to instantly wow, but there's enough to admire for it to be a redundant issue about five seconds into the game. Even the ambient tripped out soundtrack works well. It's the sort of game you'd imagine Maclean's old mate Jeff Minter would do a wonderfully acid drenched interpretation of. With Llamas. Having recently bought an old Tempest arcade cabinet off of Maclean, the two should get their heads together.

Being a 3D game, obvious concerns emerge over whether the camera misbehaves. Initially you might find your blob slipping out of view and wondering why the game doesn't shift the camera itself to give you the optimum view, but its semi-automatic approach actually works very well, for example zooming out so you can keep track of all of your blobs, but still allowing the user to perform 90-degree shifts on demand (via the symbol buttons), meaning any perspective issues are taken care of fairly swiftly and painlessly. It's hard to imagine a more graceful system, and in conjunction with the use of the superb analogue stick the whole game feels as slick as Mercury itself.

Wireless two-player multiplayer is also sure to be a big part of Mercury's appeal. From what we understand it's a case of being first past the post, with the other player appearing as a ghost. No actual mini-games a la Super Monkey Ball have been revealed, and it's likely that many of the numerous ideas Ignition has planned are being saved for the inevitable sequels. Theoretically the PSP can support up to 16 player multiplayer, and it's fair to say Maclean and co have a truckload of ideas of how to make a cracking multiplayer for inclusion in future incarnations of Mercury.

Mercurial

Mercury is undoubtedly the most interesting project from Maclean since IK+ emerged back in 1988. However brilliant his plethora of Snooker and Pool games were, long-term fans of his '80s work will rejoice at this sudden change of direction, and similarly applaud the emergence of a concept that is as exciting as it is innovative. Whoever said the PSP would be home to endless ports and tired shovelware should have Mercury pointed in their direction. It's a true return to originality just at the point we'd virtually given up on the prospect, and frankly we're itching to have another go already.