Supreme Commander

Still not a Diana Ross-based RTS.

Normally when developers invite journalists for a hands-on preview of their latest game, they're exceedingly careful not to offend those journalists for fear of getting a bad write up. So when Chris Taylor compares your humble correspondent to Hitler, it betrays an unusual degree of confidence in the game that's had RTS fans super-excited since it was announced last year: Supreme Commander. (It's okay - he was only joking. At least I think he was only joking when he compared my lack of strategic foresight to that of the leader of the Nazis...) In any case, it turns out that he's got good reason to be confident: the aforementioned hands-on session, which took place in the Seattle offices of Gas Powered Games recently, provided a good opportunity to scope out the game's strategic depths and to check out the features that everyone already knew about.

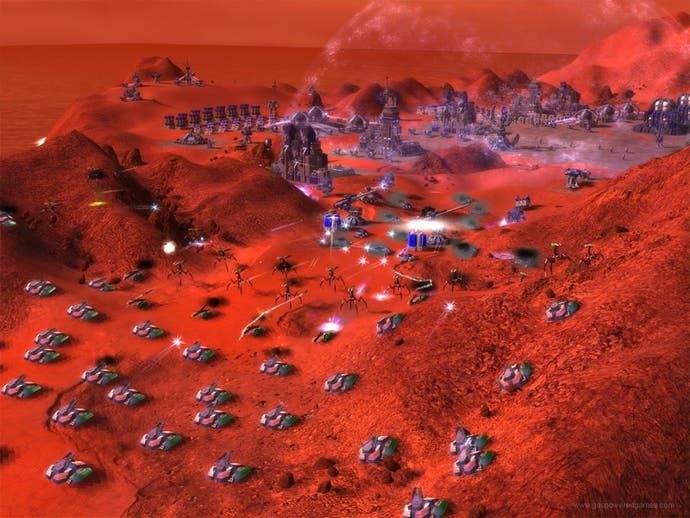

So here, in case you don't know what everyone already knew, is what everyone already knew about: Supreme Commander is the spiritual successor to Taylor's 1997 RTS title, Total Annihilation (or "my previous RTS game" as he describes it). The game features three different armies (the United Earth Federation, the Aeon Illuminate, and the Cybran Nation) and two resources (mass and power). Each army's commander is made manifest on the battlefield in the shape of an Armored Command Unit - a mobile general who is both powerful and vulnerable (since his death results in game over). The game allows players to zoom right out to see a strategic overview of the battlefield, and features support for a dual-monitor display to allow players to simultaneously zoom in on one screen and out on the other. It features a full range of land, air, and sea-based units, which can all be given waypoints that can be dragged around after they've been laid down. And it's got big maps.

Indeed, after a brief tour of the company's offices, settling down to watch the E3 demo of Supreme Commander is a convincing reminder of the game's main distinguishing feature: scale. Huge scale, which leads to increased strategic scope thanks to massive maps, a bona fide naval strategy, and offensive options that only become possible during prolonged battle as resource-hungry long-range and experimental units finally come into play (along with actual, honest-to-goodness devastatingly powerful nukes).

Taylor explains later that it's this that will distinguish the game from other similar titles - an expanded range of strategic options that unfold during later stages in the game. "I started off with the goal of making something more strategic," he says after giving us a chance to check out the game for ourselves. "I felt like we talk about strategy in RTS, but we really were playing something highly tactical. Yes you can have a strategy that unfolds inside of a small context, but strategy is something that I like to say happens before the battle; tactics happen during. So if you're playing an RTS and you don't have any time to create a strategy because you're immediately thrust into battle, are you really playing something that allows your strategic mind to do its thing?"

It's at this point that Taylor decides to throw in a characteristically unexpected counter-attack: "I felt that there was more we could do, so the bigger maps, the more exciting units, the level of zoom - when you put all those things together... well actually now you've played the game, do you think you're playing something new?"

Well that's an interesting question. Which I'll get round to answering in a little while. Because actually, the first thing you notice when playing the game is an uncanny sense of familiarity. When it comes to the hands-on part of the tour, what's immediately apparent is that this is a game that is squarely aimed at dedicated fans of the genre. It does everything you'd expect an RTS to do, but slick and polished, with a little bit more thrown in for good measure. It's an impression that Taylor confirms when he says: "You have to really know who your audience is and you have to go after that audience in a serious way, so we've really, truly gone after a hardcore market here with Supreme Commander. I took every single thing I thought worked in my previous RTS game, and I went forward with it, and everything I thought did not work and I left it behind."

So the game starts off with the same build-units-and-extract-resources pattern that will be instinctual to any seasoned RTS nut: lay down your build queue, harvest resources, and quickly create as many units as possible with which to overwhelm your opponent. Certainly that's what I did in my first game, and, without really knowing what I was doing, I managed to tank-rush my opponent into submission. From this perspective, the only thing new about the game seemed to be its superbly streamlined interface and the zoomed-out strategic view, which replaces units with icons.

But this is something that Taylor readily acknowledges: "The interesting thing about Supreme Commander is that the smaller maps make it play more traditional - land-based, early rush, race for resources." Here's the clincher, however: "As the maps progressively get larger and larger, those strategies stop working - you can't build a tank rush because you're not even on the same island. If you build a bunch of aircraft, by the time they fly across the map they're halfway out of fuel and they'll have to deal with air defences. Now you've got things like spyplanes, your big strategic nukes, your naval component. If you don't have a fuel model set up, naval elements are useless because you're moving everything you need using the air. With a fuel model that gives your aircraft a limited range, you need a forward airbase. Naval gives you the ability to clear land and it creates another angle of exposure that can be very devastating."

This degree of enhanced strategic scope is something that only becomes apparent after a few games. Like my second game in which I tried to tank-rush again, but after failing to take out the enemy ACU with my initial waves of attackers, my opponent was able to regroup and shut down my resources due to his better control of the map. Or my third game, in which I was able to sneakily observe my two opponents taking each other out before going in for the kill. Or my fourth game, in which I dominated for about an hour before realising that I hadn't invested in any long-term strategy, and was quickly taken out experimental technology belonging to various opponents (even a suicide-bid for revenge failed, as I tried but failed to march my ACU - which goes up like an atom bomb when it's destroyed - into my nearest enemy's base).

So yes, to (finally) answer Taylor, it does feel like playing something new, especially in the later stages of a battle. The strategic complexities of the game only reveal themselves gradually, as longer games allow experimental units to be built (like lumbering giant mechanised spiders and beetles, or flying saucers that take up the whole screen when you zoom in), or the transformation of your ACU into an extremely potent offensive weapon, or the hatching of strategies and counter-strategies. In fact, wandering round watching other games in progress demonstrated that the ebb and flow of battle, over games that lasted several hours, was actually just as much fun to observe as it was to initiate.

"It would be a failure if we couldn't create a game that made people believe that there's a new way to win," says Taylor. On that count, it looks like the game will be a success.