Final Fantasy 8 redefined the series' relationship with fantasy

Happy birthday!

Final Fantasy 8, my very first Final Fantasy, turns 20 this year. We all have that one memory of the first game we put into a brand-new console, and this is mine - the opening sequence on the beach, the waves lapping against the shore, the first strands of Liberi Fatali immediately giving me goosebumps. You always remember your first love, and yet I now know that this game had flaws, especially when you look at it in context of what came before it and what succeeded it.

How do you follow a hit as big as Final Fantasy 7, a game that gave your series a global audience and for many players serves as a blueprint for what Final Fantasy is? The slightly disappointing answer is that you try and give players more of the aesthetic that proved popular. FF7's design featured very modern technology and a theme exploring the ills of misusing technology that is still very topical. FF8 subsequently doubled down on the modern visuals with seemingly adult characters, a modern setting and a very militaristic theme.

Where FF7 stuck with the series' roots with an environmental message, using magic as a metaphor for our own natural resources, FF8 made magic less magical, more utilitarian, an approach signified by the draw mechanic that stands in stark contrast with the impressive, otherworldly summons. Magic in this game is no longer a life force but a poison, causing amnesia and feeding corrupt sorceresses hellbent on disrupting peace. The fantasy elements weren't removed, but gained an unusual negative connotation.

Technology in Final Fantasy, on the other hand, used to be a disturbance to the natural order of things. Think of how airships were used as instruments of war in FF4, or how most vehicles in FF7 are developed by evil megacorporation Shinra, their failed prototypes littering the slums. In FF8, the design of the Gardens and many of the settings such as military bases, prisons and research facilities normalise technology as part of the landscape. This game all but equated modernity with the settings and instruments of war. FF8 leaned further into the trope of the seemingly never-ending war against an oppressive empire, itself a pillar of Western fantasy as social commentary.

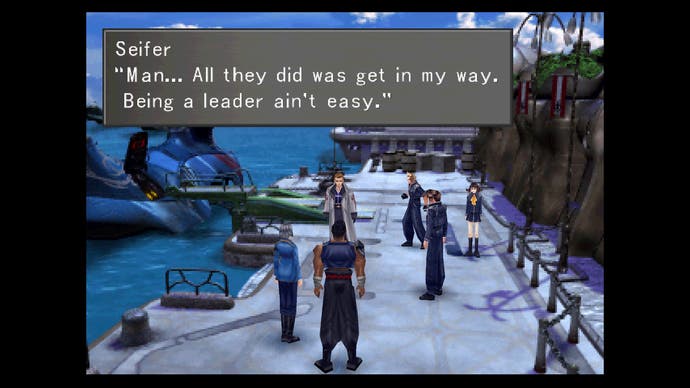

War and the occupation by a greater power may be a mainstay for Final Fantasy, but FF8 normalises this state instead of actively opposing it in the way other parts of the series do. Despite there being only three Gardens, specialised military schools, their part in worldwide peacekeeping operations between nations is portrayed as substantial. At a time when we actively question games' reliance on violence, the obvious pride with which a 17-year old wields a shotgun in this game feels weird. Final Fantasy has a dissonant relationship with violence at more than one point: if something looks like a monster or a masked soldier, you're free to kill, but if a character has relevance to the plot and more importantly your own heroes, this creates a moral dilemma. When Irvine is tasked will killing Edea, who turns out to be his foster mother, he is unable to. That in itself is understandable, but he subsequently frames his inability to pull the trigger "when it matters" as a shortcoming, a failure to do what is expected of him. In FF8, you're only ever on the offence or defence - Laguna protects a peaceful village by force, Squall cuts down intruders in Balamb Garden. As a mercenary, violence is very much an expected reaction of you, even at increasing personal cost.

Yet the element of camaraderie and the modern setting are two things I really enjoy about FF8. Both make it a game that as a teen you have no problem dreaming yourself into, when school as you know it is just the same old thing, criminally lacking in giant swords and tyrannosaurus. FF8 is closer to real life: you might not need magic to be someone special , and even your characters' unfairly good sense of style and proficiency with various weapons isn't what defines them. To a teen it's mildly reassuring that even the cool dude who's good at martial arts still has to worry about failing his classes.

All successive instalments of Final Fantasy went into a much more interesting direction regarding war. FF9 contextualised the effects of war further than before by not treating it as a past event, and showing its direct consequences on anyone who wasn't you, a powerful warrior with the ability to take on their foes. In FF10, increasing powerlessness in the face of an enemy behaving like a natural catastrophe gave an understandable motivation as to why different forces started turning against each other. FF12 was all about ending a war not by prevailing over your enemies, but by removing the source of the conflict, which in good Final Fantasy tradition once again turns out to be misused magic.

Yet FF8's narrative never advocated a peaceful solution, and left little room to doubt your own methods. A story becomes much more interesting when the hero realises their own hand in the proceedings, and FF8 left a lot on the table in this regard. Realising this, however, makes me appreciate FF13 a lot more, a game in which your group achieves their goals by purposefully challenging their destiny.

FF8 remains such a favourite of mine because it's a great showcase for character development. Squall isn't a likable character, and nothing that happens over the course of the story completely changes his taciturn attitude. It's genuine fun to see others poke and prod at him, and every instance of him expressing his emotions feels hard-earned and thus momentous. The stern Quistis is more than just an instructor, she's also a young woman, and one unused to going beyond what she's been taught. Even Selphie gets her moment to become more than the annoying sidekick once you find out she is the way she is in order to inspire happiness in others.

Over the course of the game, you get to see a different side of each of your companions, and their relationships with each other develop through conversations on the events in which each character gets to express their feelings. Whereas Noctis in FF15 or Tidus in FF10 do most of the emotional lifting for the entire group, here everyone gets to express themselves. In all this, war fills the traditional role of the fantastical as the force the characters thought they understood yet have a lot to learn about. This replacement makes FF8 unusually dark, it's fantasy elements - such as the moombas, this game's equivalent of moogles - now almost comically out of place.

In subsequent parts of the series, Square Enix restored the importance of fantasy and magic to the blend, gradually introducing a more balanced mix of historical and futuristic design elements. Final Fantasy 8 stands out as an attempt to favour one over the other. I'm glad that it introduced Final Fantasy to me as a series that trusts young audiences with serious themes. Now I acknowledge how some of its failures have made the series as a whole better, too.