Final Fantasy VI Advance

Locke up your daughters.

Think of a videogame you still love today, five or ten years after you first fell for it. Tell me what makes it special and you'll probably speak of how, at the time, the graphics transported your younger mind to new, exotic, unimagined places; of how its music perfectly soundtracked your leisure time leaving an indelible melodic stain on your mind; of how its perfectly balanced gameplay broke the separation between man and machine as your character and your thoughts acted as one; of muscle memory that will only be lost at the grave.

But, you know, you'll be lying. What makes that game still special today isn't the graphics, or the soundtrack or the gameplay so much as the memories of your life at the time you first played it. Old, beloved videogames, like old, beloved songs or films, unlock the sights, smells and emotions of where you were and what you were doing when you first encountered them. Super Mario World is grazed knees, orange squash and long, hot school holidays; Gunstar Heroes is the two-player Christmas morning when you and your brother got along; Tetris is the underside of a duvet saturated in yellow Gameboy light with the sound turned down to avoid detection.

This subtle but unshakeable historical subjectivity often holds videogame critics' opinions ransom when looking at re-releases of classic titles first loved in younger days. Nostalgia makes it difficult to separate a game's inherent qualities from the quality of the memories of playing it in happier, simpler times. With that in mind this correspondent decided to play Final Fantasy 6 - a game revered by both the Final Fantasy series and RPG aficionados perhaps more than any other - to fresh completion in the hope of discovering if the experience was the epiphany his fifteen-year-old mind routinely assures him it was. The warm mist of wistfulness is quickly burned up once you're forced to spend thirty hours alone with an old flame and so any sceptics should rest assured that is as sober and contemporary an evaluation as Eurogamer could prepare.

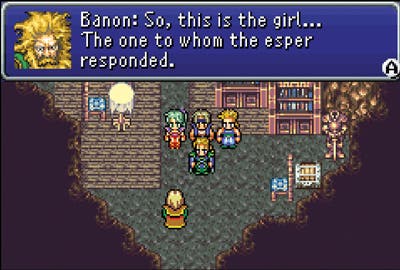

What is immediately apparent is just how surprising Final Fantasy 6 is - even today. Despite sharing many conceptual similarities - the towns, dungeons, exploration and menus - in many ways it is deeply atypical to the Final Fantasy series. The game features a large ensemble cast instead of a single protagonist and your control switches between these characters consistently throughout the game, giving the effect that you're taking part in an expansive play. You are given freedom to name many of the game's characters and, interestingly, all of these controllable personalities have completely distinct and unique ways of behaving in battles - all factors scarce seen in the following titles in either the series or the genre.

The story, the most solid bedrock upon which the game is founded, is remarkably consistent, engaging, understandable and funny to a western mind. It suffers none of the impenetrable anime excesses of many other games in the genre. Characters have believable motivations, flaws and quirks, and are all richly developed. The metaphysics are kept to a minimum as this is (at least initially) a more earthly tale of politics, empire building, greed and lust for power. Set on an unnamed world, the game presents a steam-powered society that mirrors mid-nineteenth century technology, class structure and arts. The emperor Gestahl - supported by his generals, the delightfully psychopathic and unforgettable jester Kefka Palazzo, the good and upright Leo Cristophe and later defector Celes Chere - is seeking to combine magic with machinery and so infuse his soldiers with magical powers. You assemble a ragbag assortment of princes and paupers as they form a resistance movement against the Empire and seek to undermine their plans.

The plot is communicated by an excellent translation - a fresh blend of Ted Woolsey's original Super Nintendo work and some more orthodox new translation from the Japanese allowed for by the larger GBA cart size compared to the SNES version. While fairly conventional in its pitting of good and evil against each other, the narrative is raised to unexpected heights by the brilliantly imaginative set-pieces that spur it along - most of which cleverly combine storytelling and gameplay. The result is a near Monkey Island-esque domino run of (often interactive) cut-scenes and witty dialogue exchanges which delight throughout in a way that few games have really managed since. When battling through dungeons seems to be dragging the game's pace down (and, in this respect the game is far easier on the ADD kids than most grinds) you're always pulled along by the promise of the next narrative set-piece.

For example, in the game's most famous scene, one member of your party is required to pose as an operatic diva in order to catch a kidnapper. As the rest of your squad watches from the theatre's upper circle, you control her in the dressing room, learning your lines and stage directions, before stepping out to attempt to follow what the directions the script demanded. The whole scene is set to a beautiful aria (Aria di Mezzo Carattere) composed by series stalwart Nobuo Uematsu and, once the kidnapper turns up and your team have rushed the stage to intervene the scene, you realise the game has successfully tight-rope walked a line between beauty and farce that few games ever manage.

The game holds the serious and the sweet in delicate tension throughout. At one point late in the game, the sole character under your control finds herself in the lone company of an elderly, ill gentleman stranded on a small desert island. You have to fish on a nearby beach in order to subsist and keep his health up but, depending on how you fare at nursing, your patient eventually passes away. With nobody to live for, your character becomes so depressed that she (under your control) scales the cliffs at the north end of the Island and throws herself, slow-motion, onto the rocks below in a lonely, hopeless suicide attempt.

Conversely, at another point a party members' granddaughter, forbidden from joining the team by her concerned relative, successfully follows your group into some dangerous caves. She's a ten-year-old wunderkind painter and, following an amusing exchange where she butts into the middle of a battle to try and paint the hapless monster you're attacking, she joins your party. One womanising character inquires as to her age before sighing and, in an aside to camera, bemoans the fact she probably won't be around in six years time to enjoy...Likewise, one of the more prudish characters in your team finds himself in a bar attracting the attention of one of the venue's dancers. She clearly delights in making him squirm with her inappropriate advances, culminating in her asking if he likes her assets, 'Humpty and Dumpty'. Many of these risqué jokes would never make it into a mainstream, teen-rated game these days (and indeed, many of them were cut from the original western SNES release at Square's behest) but they add a character and believability to the story that's so often missed.

Battles, while more orthodox than the plot, are still inventive. Monsters are encountered either randomly or during specific cut-scenes and defeating them reaps the usual experience points to level up characters and improve their abilities. Characters all behave differently according to their back-story - for example the Ninja has a 'throw' move while the Monk has various Street Fighter-esque special moves which must be inputted with quarter and half turns on the D-pad. This flexible system means there's a lot more diversity to characters than in the vast majority of other RPGs and it's surprising that so few subsequent games have picked up on the benefits of such a system. You can equip characters with their own bespoke weapons (for example the gambler uses darts and cards as his offensive weapons) and up to two relics each. These special items bestow unusual bonus effects on the character. Later in the game it's possible to equip characters with magicite magical shards which grant the character their own summon spell while simultaneously funnelling experience points towards gaining certain spells. This allows players to customise their team and balances the more defined and inflexible abilities that come with each character.

Aside from the aforementioned translation tweak to the game, this GBA conversion adds four new Espers to the game (Leviathan, Gilgamesh, Cactuar and Final Fantasy VIII's Diablos), three new spells as well as a new dungeon and the Soul Shrine area levelling area. There's a quick save option, multiple save slots, a cursor memory function and lots of those elements that were missing from the DS version of Final fantasy 3 which hurt that game so much. Some of the censorship that appeared in the western Super Nintendo release has been carried over to this port, for example Celes is no longer chained and beaten during her interrogation in South Figaro and various instances of sprite nudity have been reworked but, generally, this is a brilliant conversion of the original Japanese release.

For those who first fell for Final Fantasy VI many years ago, the experience will not disappoint in the way that many revisited interactive memories can do. In 1994 the fresh gameplay ideas Final Fantasy 6 brought to the RPG genre, coupled with the highly enjoyable story, brilliant ensemble cast and stirring score would have made the game an easy, trailblazing Eurogamer 10. It's either a remarkable testament to the original development team's vision and skill, or a damning indictment of a genre that this is so very nearly the case thirteen years on.

Final Fantasy VI is due for a summer release in Europe and will be published by Nintendo.