Finding the first ROM: original Xbox lead Ed Fries' double life as an arcade archaeologist

Chips with Fries.

At the Portland Retro Gaming Expo, Ed Fries has just finished an on-stage presentation with Atari veteran Ron Milner. The talk - sometimes technical, often playful - focused on Fries' effort to uncover the first ever video game Easter egg, which turned out to be hidden deep in the circuitry of Milner's 1977 release Starship 1.

It is late in 2017, and it is apparent that the former vice president of game publishing at Microsoft is enjoying an experience very different from his visits to GDC and E3 during the first Xbox's heyday. In Portland there are no PRs nervously flanking his movements through the crowds. Fries, Milner and a handful of the audience chat casually about early Atari hardware, and nobody even mentions what it was like to lead the team that created the original Xbox.

Yet despite the relaxed atmosphere, Fries can't quite settle. He is animated, and while he's enthusiastically chatting, eventually he can't hold out anymore. "I've got something exciting to get back to in my hotel room," he explains, before dashing off.

It turned out that a friend had dropped off a selection of prototype arcade boards secured from an early Atari engineer. And Fries had been waiting a long time to see them up close. What was on those boards? Fries and some fellow enthusiasts might have uncovered the very first known video game ROM.

ROMs - or more accurately 'Read Only Memory' chips containing data and code - were hugely significant in making the mass production and distribution of games more efficient, affordable and practical. Before that, when engines like Unity and Unreal were a far-future fantasy, making a game was effectively a work of electronic engineering. Titles were spun from primitive components and 'logic gates'. With the arrival of the video game ROM, the likes of cartridges and multigame arcade systems became a reality. To find the very first ROM, then, would be to confirm a significant moment in games' evolution from fad to bona fide industry.

The thing is, Fries hasn't retired so as to reinvent himself as an archaeologist of arcade hardware. He is still on the board for numerous technology and gaming companies, and remains famed as a 'co-founder of Xbox'. He just seems have found a quiet double life. Far from the light and noise of the games industry, he toils away working as a volunteer historian in the quest to preserve video gaming's forgotten past.

"I've always been a tinkerer and always liked to make things," explains Fries, whose father was an electronic engineer with a workshop he gladly opened to his children. "That's why I made video games as a kid. I was always making things on the side, even when I was at Microsoft. So I like this stuff. I have stayed involved in business stuff, but I love what I call - as do my kids - my 'procrastination projects'."

It's clear from Fries' enthusiasm that he sincerely adores creativity via gaming's past; indeed, this is the man who remade Halo for the Atari 2600 in 2010 as Halo 2600. But there is something more serious to Fries' undertakings with a soldering iron, as evident in his technically detailed blog documenting his practical history of gaming hardware.

And Fries isn't content with the console-like convenience of arcade systems such as the Neo Geo MVS. He favours older forms, having restored a broken Computer Space cabinet from 1971, and revived a 1974 Gran Trak 10, the final release version of which was previously assumed to contain the earliest game ROM. "I wanted to learn something about how you make a video game without even having any code," he says of the Computer Space project, which he in part worked on with his father. "How do you make a video game just built out of logic gates? That's where my first story came from, so I wrote 'Fixing Computer Space' for my own blog."

But what of that ROM? It was common knowledge that Gran Trak 10 included the 'first' ROM, but Fries and others believed an earlier version of the game existed, perhaps in a pre-release cabinet sporting an earlier ROM. For one, on the final cabinet a track was missing. Fries and his collaborators had found an unpublished black-and-white race circuit on the back of an Atari flyer promoting the game to arcade operators. The same circuit had even been spotted in a photo an early Atari engineer took of his kids playing the game. Just where was this version of the pioneering game hiding? Could it be on an undiscovered ROM? Perhaps. Now all Fries had to do was find the 1974 chip, and get it working.

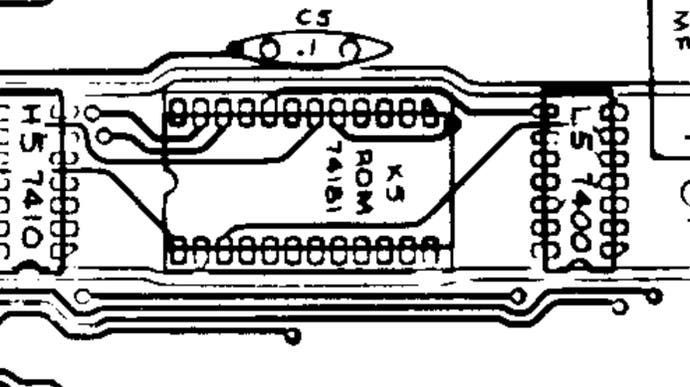

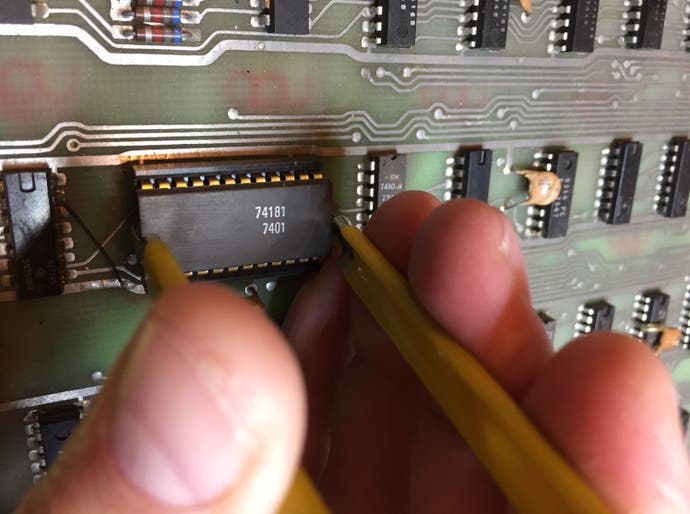

"We had a lot of copies of this ROM marked with the number 74186 [from Gran Trak 10 boards], but we had some schematics and things that said there might be an earlier ROM; number 74181," Fries explains, pondering if the numbering could allude to a version of the game with the mystery track. "I couldn't find anyone or any way to verify it. I looked for months, and finally I just decided that maybe if I put the story out, that would help."

Six month after Fries' plea for information, he received a Facebook message. It was from John Hardy, one of the co-founders of America's National Videogame Museum.

"He said they had just bought a bunch of boards from an early Atari employee, and that the employee thought they were Tank boards, and would I like to take a look. Well, I said 'sure', and told him that if there were any big chips, to take pictures of those and send those to me."

One of those boards turned out to in fact be a Gran Trak 10 board, and Hardy sent over some photos. One showed a ROM marked 74181, dated January 1974. After meeting Hardy in a hotel during the Portland Retro Gaming Expo, Fries took possession of several arcade boards, including one sporting the mysterious ROM.

After the expo, he rushed home. "I carefully pulled the chip out, put it in my Gran Trak 10 machine, fired it up and there it was. It was clearly the thing we were looking for. It was exactly what we thought. The first video game ROM." Ed could see the unreleased racing track in front of him. But the story didn't end there.

In June 2018 a reader commented on Ed's own blog post about the Gran Trak 10 ROM, asserting that there was an earlier example of a ROM in 1973's Volly, a Pong clone by computer manufacturer Ramtek.

"He's a guy who knows what he's talking about," says Fries, who researched the commenter and found them to be a reputable contributor to the MAME community.

"They found a very small ROM in the Volly game," explains Fries. "It's a 32-byte ROM as opposed to the 2000-byte in Gran Trak 10. I haven't been able to find out what's in the Volly ROM, but it's so small - even with it being a Pong game - it can't hold any graphics. My guess is that what this ROM has is information on angles [the ball bounces] off the paddle."

So That Gran Trak 10 ROM might still be the first true game ROM, but it isn't the first ROM in a game. Simply put, there's more detective work to be done. "I just haven't been able to find any schematics or other evidence for this Volly ROM," admits Fries. "But I have found enough to convince myself that this guy is right."

And that is the point of the effort of Fries and his contemporaries' work. Documenting the technical foundation of games - rather than stories of studios and game release dates - is an arcane process where any claim to uncovering a 'first' might soon be usurped.

Fries is far from done, too. While the precise details of the first video game ROM are still to be confirmed, he has plenty of other investigations underway. He's spent much of his recent spare time on a new arcade project due to be detailed in talks he'll give at coming games conferences. And he has just finished restoring a 1975 Gun Fight cabinet; notable as the first game - as far as Fries knows for now - to use a microprocessor. But now he must turn his attention back to his latest endeavour; a 1982 Star Trek cabinet that houses the Electrohome G08; a monitor infamous for its habit of bursting into flames.

"I'll try not to have anything catch fire as I work on it," he promises, with a mischievous smile.