From Daredevil Dennis to Die Hard Trilogy: Simon Pick has a hell of a tale to tell

"Let's make three games! It'll be fine."

Imagine being the only person in the building allowed to go into a room because there's a top secret console inside. It's bizarre and yet it happens - console manufacturers are famously secretive about their new hardware. And this is how a man called Simon Pick found himself shut away in a room with a new machine Sony was working on, called, at the time, the PSX - better known to us today as the PlayStation 1.

Pick worked at a studio called Probe Software, which had been commissioned to make a PlayStation game for the Crystal Maze, a TV game show - except it wasn't on the TV at the time and there were problems with it, so the game tie-in was abruptly canned. Pick had signed an NDA to work on it, and Probe had PlayStation hardware because of it, so both now needed something else to do.

Cue a piece of history in the making: Fergus McGovern, the boss of Probe Software, pokes his head around the corner to make a suggestion to Simon that he cannot resist. "Sorry, it's cancelled," McGovern says, according to Pick, who I'm talking to now. "But I can offer you this other thing which is a film tie-in." Simon Pick's ears prick up. "We want to make a Die Hard Trilogy video game. Are you interested?"

"Oh my god yes that sounds awesome!" Pick coolly replies. And he leads the project from there.

The original idea for the game wasn't the same as the Die Hard Trilogy we know now, though. We know it as being three games in one: a third-person action game, a light gun shooting game, and a frantic arcade driving game. But originally, the idea was more muted. McGovern envisaged one game with three sections, rather than three separate games, which makes sense - no one knew how to make 3D games at the time and no one knew how to work with PlayStation hardware. But Pick was lit up. "I said, 'Let's make three games!'" he tells me. And yes you heard that right. "It was my idea to make the three separate games."

He quickly worked up an idea of what he wanted to do, which was somewhat indicative of the approach to game-making at the time. "I loved Virtua Cop so we ripped that off for Die Hard 2," he says. "I loved Crazy Taxi so we ripped that off for Die Hard 3. And I loved - and I still love - Robotron, so Die Hard 1 was a sort of 3D version of Robotron."

Simple. Or was it? Because it quickly became clear to Pick and team that they'd taken on more than they could comfortably do. There was only Pick and one other programmer on the game, plus some artists, plus some people making tools, and as I've said, none of them knew how to make 3D games, and none of them knew PlayStation. Sony didn't really even know PlayStation at that time. Development libraries weren't finished and the light guns were prototypes. The guns the studio was sent wouldn't even turn off.

"So for months," Pick says, "if you were playing Die Hard 2 with a light gun - and then you went back to the menu and played Die Hard 3 - the whole game would crash because the light gun was still connected and it was still trying to access Die Hard 2 code. So we couldn't actually test the game end-to-end for ages until they gave us a software update. QA was saying, 'You need to fix this!' And I was saying, "I can't!"

The deadline - the original deadline - was for the game to launch alongside the Die Hard 3 film, which released 19th May 1995. Oh my wrinkles. But there was no way Pick and Probe was going to hit that date. 20th Century Fox had to bend. "Fine, we'll release it at Christmas," it said. Even with the extra time, though, the project struggled. Pick remembers the game failing Sony's certification process at least once, and there's a suggestion it only eventually passed because of a bit of backroom pressure from 20th Century Fox.

"I hear on the grapevine," Pick tells me, "that basically 20th Century Fox [convinced] Sony to get it approved and released. 'Look, this game is big, it's going to be Christmas number one for you. You're going to make lots of money on it, Sony, and we do not have time to fix the bugs. So just get it into production.'

"These are the rumours," Pick says. "It may or may not be true. But that's what happened: it was released in time. And it did very well on some charts. It was Christmas number one."

"But," he adds, "it was a horrible, horrible time. Really hard work. And I felt like I didn't sleep for about 18 months. It was a nightmare."

Maybe surprisingly, Die Hard Trilogy is not the reason I tracked Simon Pick down. I didn't honestly realise he was involved with the game until I did some more detailed research before we spoke. Pick's career is a bit like that: full of surprises, as you'll see.

I tracked Pick down because of another game he made, a fair few years before. It's a game that's equally important to my gaming memories as Die Hard Trilogy - I spent a very enjoyable summer hunched over an ironing board in a baking hot conservatory shooting that light gun - and perhaps, in some ways, it's even more so. But it was a game I was beginning to lose all hope of anyone else knowing, because whenever I brought it up, I'd get blank stares from everyone - a not unfamiliar reaction, I must admit. It meant I'd even begun to question whether the hours I'd spent jumping my little motorbike man over trees and houses in this game, and ducking giant spiders and doding police, had ever really happened. Had I made it all up?

Now I've spoken to Pick, though, I'm feeling much more sure of myself, and partly because I know there's a great chance many of you will know the game I remember too. "So almost anyone I talked to who's in their fifties has played it," Pick says, casually lumping me in with an older crowd but that's OK, Simon Pick, I'll take it. If you're of a certain age and you went to school in England in the 80s, and your school had a BBC Micro, then there's every chance you'll remember the game I'm now going to name. Here goes. Daredevil Dennis - do you remember it?

It was Simon Pick's first published game - the game that started it all, really - and he was only 16 years old when he made it. His mother inherited a bit of money and split it with him, affording him the chance to buy a BBC Micro to make it. She, for her part, bought a dishwasher for the family. "In hindsight, I feel bad," Pick says. Don't be, Simon Pick, because without it, where would we be?

Pick's passion and speciality at the time - and actually, it would stay with him long after, even to this very day - was arcade conversions. With Daredevil Dennis, though, he decided to embark on something original and new. He knew that a company down in London called Visions Software Factory was doing a similar kind of thing so he just needed an idea to build on to pitch to them. It didn't take long for him, a teenager in the 80s, to come up with one, but you might want to cover your ears as he explains it. "Daredevil Dennis started out as a really bad-taste game," he says. "It was set in a hospital and the main character was in a wheelchair." He winces at this. I also wince at this. "It was called Escape the Hospital or something, and you had hospital-themed things in the way that you had to jump over and escape."

Nevertheless, he had a game, and he stuffed it excitedly in an envelope and posted it to Visions in London. The story then apparently goes that Visions, a tape duplication business primarily, received the envelope and loaded the game on the only BBC Micro it had, at reception. "They had this small reception attached to this big tape duplication factory, and whoever it was who looked at submissions, left my first version of Daredevil Dennis running on the computer there," Pick says. "And apparently people were coming in to talk about tape duplications and they were seeing the game and they were sitting and playing it. And I am told that when it was time for them to go and have a tour of the factory, or have a meeting, they were going, 'Oh wait a minute! Wait a minute! Let me just finish this level.'"

Pick had hit upon something, and interest would continue to grow at Visions until the company decided to make him an offer. "Write it in Basic," Visions said, "make it colour, add some sound effects, and..." Perhaps most importantly: "Make it not a wheelchair." Daredevil Dennis was born.

Pick built the game that summer, travelling up and down from his home in North Yorkshire to Visions Software in London, while learning Assembly language to program in. Eventually, he had all 8KB of memory (after system deductions) filled with the game he'd made, and Visions Software released it. Simon Pick was now a published game-maker. More to the point, Simon Pick was now loaded, comparatively speaking. Vision Software had paid him a then eye-watering, for a teenager in the 80s, advance of two thousand pounds. "I was like , 'Wow I'm rich!'" he says. He was even offered a royalty deal of 30 pence a sale thereafter, not that Daredevil Dennis would sell very well because of the rampant piracy of the time, and not that Visions Software would continue paying it for very long, because it went bankrupt. But none of that really mattered to Pick: he was a success.

There were newspaper articles about him and his name circulated around the school. He even apparently won a BBC Micro for the school in an unrelated game-making competition, at one point. "Everyone was going, 'Ooh, Simon," he says. Well, not quite everyone. There were some people from the computer club he frequented who were jealous of him and his success. "You couldn't write this game and you couldn't write that game," they would say. And even though it was true, Pick hastens to admit, it had the career-shaping effect of spurring him on. "Right, I'm going to keep at this and I'm going show them that I can do better," he told himself. And he did.

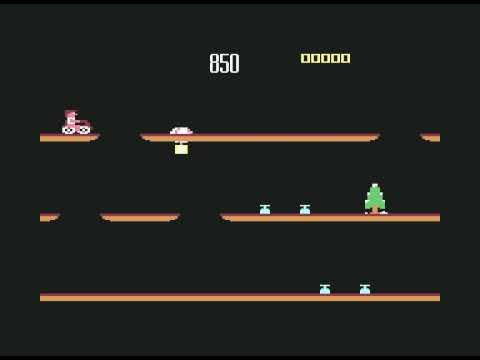

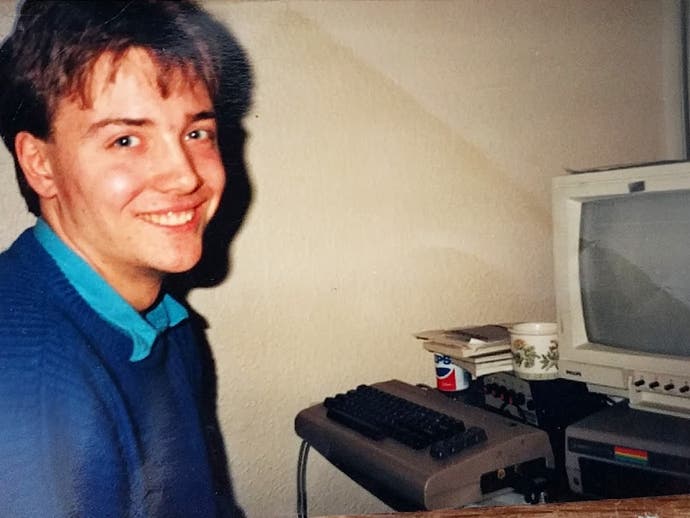

Daredevil Dennis on the BBC Micro was followed by Daredevil Dennis on the Commodore 64, which was actually a substantially different game. It wasn't about progressing through a level line by line any more, as if you weere reading a book, it was more of a platform game. This was Pick proving those computer club naysayers wrong, but more importantly, it meant he now had a Commodore 64, and this would be the key he would need to unlock the game development door ahead.

A string of C64 games would follow. Mad Nurse I'm sure he'd rather forget, but the drum-machine tool Microrhythm he managed to sell to British Telecom's software division, and in doing so, established an important connection to come. He also managed to land his first work-for-hire job for Konami, porting the legendary arcade game Gradius/Nemesis to C64. "It was an absolute nightmare," he says. It overran and interfered with his by-then university work, leaving him without much sleep.

Nevertheless, that seed he'd planted with British Telecom came to fruition when after finishing university, former BT exec Jane Cavanagh approached him with the offer of a job. She was launching a new games company called The Sales Curve (later called Storm, then SCi, then Eidos when SCi acquired it, then Square Enix when Square Enix acquired it) and she wanted to offer Pick a job. "Do you want to come and be a Commodore 64 coder?" she originally asked. But then, when he went to meet her about it, she upgraded the offer. "Actually," she said, "we're looking for a manager to build the team - are you interested in that role instead?"

So it was that Simon Pick built the first development team at The Sales Curve. While there, he'd bring arcade games like Silkworm, Shinobi, Star Control, Indy Heat and Narc to home computers, and I'm sure you played some of them. But did you play a game called Rodland, which he solo-converted for NES? I'd be surprised if you have. I'd be even more surprised if you have a good condition copy of it lying around somewhere, though if you do, you're in for a shock. Mint condition PAL copies of Rodland go for up to two grand on eBay - there's one there right now at that price. It might even be one of the rarest NES games around.

But it's not because Rodland is legendary, sadly. It's actually because it was released at a time when everyone was moving over to SNES, so only a very limited amount of copies were made. And it was only released in Spain in PAL territories. "So saying it's the rarest one is saying it's the one that sold the least, so I shouldn't be too proud of that!" Pick says, with a grin.

Pick's last game for The Sales Curve would be SNES game The Lawnmower Man in 1993, which he was the sole engineer on. It mixed side-scrolling with rudimentary first-person 3D, which I remember gawping at in magazines at the time, though it ultimately wouldn't be very good. After that, Pick moved to work with Fergus McGovern at Probe, where the Die Hard Trilogy story would unfold.

It was all forward momentum for Pick at the time. He was young and the trajectory for him had always been up. Sure, there were bumps, but everything generally was improving: his standing, his income, and his prospects. Die Hard Trilogy crowned that early era for him. Not only was it a huge success, he was on a royalty deal for it, meaning he made money from every copy sold. It was the last royalty deal he'd ever be offered, and he'd burn a few bridges cashing it in, but all that really mattered to him at the time was it set him up for the future, and set him up to do something big: make a studio of his own - PictureHouse Software. And this is when his luck begins to turn.

How could he have known, for instance, that Spyro would come along and completely eclipse the PlayStation game his team was working on called Terracon? More infuriatingly still, had he known it would, and had Sony known it would, perhaps Terracon wouldn't have been changed from being a game about a Scout and his Scoutmaster travelling the land with a magic glove, which could shape materials in the world, into a game about an alien running around shooting a laser gun. All because Sony had said, "We like the game mechanics and we like the team, but we don't like the fluffiness of the game. We want to make it more attractive to teenage boys and hardcore gamers. Can you make it sci-fi?"

Nevertheless, Terracon reviewed as well as Spyro, so Pick and team thought it might have the same kind of success. "But we didn't," he says. "And that was a bit upsetting to say the least."

Who could also have predicted that terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers in New York would prevent the studio's second game, Boom TV, from being released? It was a PlayStation 2 game inspired by Pick's love of Crazy Taxi. In it, you'd choose a building to demolish, jump in your car and drive to it, then place explosives and bring the whole thing down for a reward. Development got nearly all the way through - you'll see how finished it looks in the video in this article. But not only was the subject matter in question following the events of 11th September 2001, the specific New York level in the game - where you had to rig a series of skyscrapers to blow - was a no-go.

"I think a lot of us just felt sick to our stomach about that because of the reality of the situation," Pick says. "I emailed Sony on September 12th I guess, the next day, saying, 'We can't publish.' And they said, 'We were thinking the same thing.'"

Sony gave PictureHouse a Lemmings PS2 project to work on instead, which again, the studio got far through development on. There was even some fledgling PlayStation Network work in there, in how you could design levels and then send them to your friends. But for reasons still unknown to Pick, Sony pulled the plug, and three strikes was all Pick could take. "At that point, I shut the whole thing down," he says. He closed PictureHouse Software. "And I went into a sort of depression and a spiral. I thought, 'Oh my god, that's it. I've been chewed up and spat out by the games industry.'"

He retreated back to a safe place, which for him, was working alone on arcade conversions of games. It was how it had all begun. Through his old friend Fergus McGovern, he got a contract with Jakks Pacific to make plug-n-play handheld devices, and though this might sound like filler work, Pick remembers it with great fondness. "It was like a return to my youth," he says. He was back using Assembly code and finding specific solutions to specific problems. It wasn't like the ballooning problems modern games faced. Pick even had a say in how the hardware worked. The Classic Arcade pinball device he worked on in 2003 had flipper buttons on the back and a tilt function. He still really likes it. "You've asked me what I was most proud of..." he says. "That pinball game is really very good."

The work he is most proud of, though, is the work he did on Burnout Paradise. After his "two years in the wilderness" were over, he joined EA to work on it. He wasn't in charge of the project and he didn't originate it, but he was responsible for an incredibly important part of it - a part you'll know very well if you've played it. "I was the lead AI coder," he says, "so if you're playing in an offline race, then you're racing against me. All the other cars are me."

Achieving what he did with Burnout Paradise meant overcoming a number of really challenging design problems. Remember, until Paradise, Burnout games were much more linear, made up of specific courses with specific racing lines on them. "But this was open world," says Pick. "You didn't know where the players were going to be driving. There was other traffic. So it was incredibly complicated," he says. "I almost failed to do it. It was getting to a point where, I thought, 'Oh my god I have completely screwed the Burnout franchise. I'm not going to be able to make this work.' But then I had inspiration and thank goodness it worked, and the game is what it is."

It's a bitter-sweet moment for Pick. He's proud of what the team accomplished, but it doesn't sound like he enjoyed his time at EA. He was one of the team now, rather than the leader, and he'd butt heads with the leadership over decisions. He butt heads with leadership on Burnout, and he did the same with the Harry Potter Deathly Hallows games he'd work on next. His fallout with the technical director on Potter even led to him resigning. "I stayed within EA," he says, "but I said to my manager, 'I can't work with this guy. He's made a really terrible decision which I disagree with strongly.'"

The terrible decision was a decision to replace Pick's team's code with code that favoured visuals over gameplay. The game was a mess and Pick would be vindicated, to some degree, when it flopped. He would be vindicated further when EA asked him back for Deathly Hallows Part 2. "I told you so," he said.

"I do sometimes think, 'Should I have one last hurrah?'"

But though development improved on the second game, the same fundamental flaws in the code existed, so it too struggled because of it. The two games were a disappointment to EA, the studios that made them were closed, and Pick was shunted to another internal studio instead. A new studio EA had bought to embrace the zeitgeist of the time: Facebook games. Specifically, The Sims Social Facebook game. Pick didn't care for it at all. "I hated every minute of it," he says. All day long he'd stare at huge leaderboards showing which in-game pieces of furniture were making the most money. "I felt sick to my stomach working there," he says. So he left.

This, really, is where the trail on Simon Pick starts to go cold, because it's the point he turns away from the games industry. The stress and the pay weren't worth it any more, he tells me, and he felt increasingly out of place with all the young people around him. "This was 10 years ago, maybe it's all different now," he adds with a shrug. With a wry smile, I tell him it's probably not.

Pick took his coding talents to Google instead, where he's now an engineering manager, running a small team doing internal things I'll never understand. Google is where he's speaking to me from today - from inside a stripped-back looking wood and metal cubicle, wearing a shirt and trousers with a security lanyard dangling on top. But he hasn't quite been able to leave games behind. Half of the work he does at Google is in accessibility, and making products work for partially sighted people or cognitively impaired people, and as part of that, he tells me he's designed a game. "I've designed a platform game for blind users," he says.

It's just a design for a game, he's quick to add, but it's stirring something within him. "I'm probably going to retire in the next five-to-ten years," he tells me. "I do sometimes think, 'Should I have one last hurrah? Should I leave Google and go and join a start-up or some games company?'" But even as he says this, familiar doubts creep in. "I think a lot of young developers would probably look at me and think I'm just some old man, and 'what do you know about it?'" he says.

Well, I've got an answer for that, Simon Pick. It's this article. If people ask what you know, point them to Burnout Paradise, point them to Die Hard Trilogy, point them to Daredevil Dennis. How many times have they had their name in the local paper at 16 years old, I wonder? Point them to all the many ways in which you've helped shape the industry you feel a bit out of touch with now.

I'd also tell them that if you were to make another Daredevil Dennis game today - and not the ridiculous Flipping Sheep game you made for iPhones in 2013 - I bet I wouldn't be the only person excited to play it.