From Mediterranea Inferno to Baldur's Gate 3: the queer ecstasy of monster-loving

Ogre joyed.

Hello! Eurogamer is once again marking Pride with another week of features celebrating the intersection of LGBTQIA+ culture and gaming in all its guises. Today, Sharang Biswas explores the allure of the monstrous, from Mediterranea Inferno to Baldur's Gate 3.

One bright Thursday morning, I walked into class and asked my NYU graduate students what they'd thought of the movie I'd recently assigned, FW Murnau's classic 1920's German silent film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Within nary a heartbeat, one of my gay students looked me straight in the eyes and declared, "Count Orlok is hot!"

This wasn't a wholly unexpected response. The queer attraction to monstrosity has long been a recurring topic of academic discourse. In 2021, in this very series of Pride-themed articles, Dr Lloyd (Meadhbh) Houston discussed - paying particular attention to Resident Evil Village's beloved and gigantic Lady Dimitrescu - how queer folks reframe, recontextualize, and reconstruct monsters in media in order to find characters with whom to identify. The shadowy Babadook and murderous clown Pennywise, for example, both briefly enjoyed the status of queer icons.

I'd like to go further. Long labelled as "monsters" and "deviants" themselves, queer people have reclaimed these metaphors, cheekily lending our attraction to monsters a romantic or sexual twist in order to reflect the multitudinous facets of what it means to be queer. Thus the era of the fuckable monster.

But what do we mean by monsters? Often that starts with our feelings about ourselves. In Avery Alder's influential tabletop roleplaying game Monsterhearts 2, in which players take on the roles of drama-fuelled teenage monsters in high school, the rules tell us that "we don't get to decide what turns us on, or who" - which here could be a violent werewolf, a frigid vampire, or a voracious ghoul of any gender, regardless of your character's notions of their own sexuality. To Alder, the complications of living as a monster among people are synonymous to the confusion of desires we experience (or lack) as we grow up as queer people.

Even the most beautiful of us carry fissures and fractures - the monsters hiding within us all, if you will - something I was acutely reminded of while playing Lorenzo Redaelli's Mediterranea Inferno, which shows us via disturbing, surreal imagery verging on horror, that pretty, young, circuit-party gays can often suppress anxiety, fear, and darkness beneath a veneer of beauty. Loneliness, fear of rejection, and uncertainty about our place in society are common monsters within the queer experience, especially for gay men in the West, where "thin, white, and muscular" dominate our ideas of who is beautiful - and thus who is worthy.

To fuck monsters then, is perhaps to let out a bit of our own darkness. The point where a broken, monstrous body meets a broken, monstrous soul - loudly, messily, obscenely - is perhaps the point where queerness can find itself.

Some games have explored the implications of queerness and monster fucking in a more literal sense. In 2016, for instance, Aleksandra Sontowska and Kamil Węgrzynowicz's solo, journaling-based The Beast made waves as a tabletop RPG in which you vividly contemplate and document your sexual relationship with a monster hiding in your house. The game not only tells you that yes, you can be turned on by things that others might find disgusting, but also asks you to revel in the queer joy to be found in the unabashed flouting of societal norms. To fuck a monster, thus, is to resist.

Even early in our literary history, monsters have been used as stand-ins for sexual difference or repression. Literature scholar Chiho Nakagawa contends, for instance, that "Vampire stories in the 19th century offered glimpses into illicit desires, allowing the writers to talk about sexuality in a way that otherwise could not be done. Even in the absence of explicit descriptions of sexual acts, 19th century vampire stories offered their authors the opportunity to hint at, or even revel in, a variety of sexual transgressions". You thought I invoked Orlok and Dracula just for kicks?

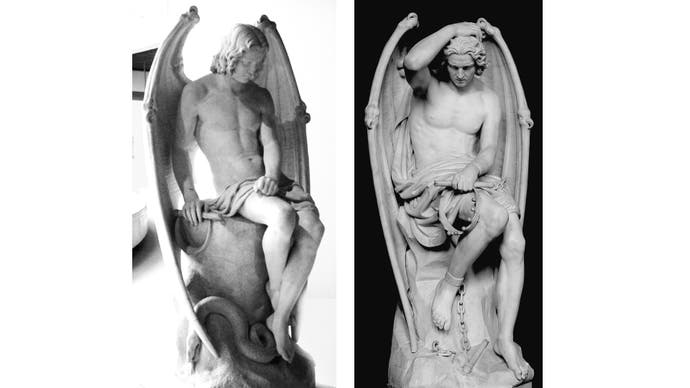

Vampires, particularly, are part of a long history of depicting monstrosity as beautiful and sexually appealing. Perhaps the most hilarious example of this is what's sometimes known as "Sexy Satan". In 1837, when sculptor Joseph Geefs was asked to create a statue of Lucifer for St. Paul's Cathedral in Lieges, Belgium, the twink he carved out of marble was considered far too hot: "The devil is too sublime", the cathedral authorities said, claiming impressionable, sensitive young women would be too distracted. But take a look below at what his brother Guillaume made as a replacement: have you seen a hornier devil? The second sculpture was approved by the Cathedral, perhaps because they realised making the devil homely was a losing battle. After all, if he's supposed to represent temptation, shouldn't he look, well, tempting?

Nearly 200 years later, games of all types continue to explore the beguilingly sexy nature of monstrosity. Glitch's Monster Prom, for instance, foregrounds its love interests as monster-hotties, their monstrous nature manifesting not in their looks but their psychology: they're nearly all psychopaths. The mermaid Miranda, for instance, is a wannabe genocidal dictator. Damien the demon is a sadistic pyromaniac. As Eric Cline wrote for Haywire magazine, "There is a willingness here on behalf of the game developers to let the romanceable characters be not just morally grey but outright mean and terrible, celebrating the fun that can come with being a monster". Could this be an outlet for queers, who are always forced to perform extra nice, lest the eyes of the heteropatriarchy judge us too uncouth to exist?

And then there's Dungeons & Dragons, the game in which the "can I seduce it?" nature of its players is notorious. The 2014 edition of the D&D Monster Manual is packed with monsters meant to titillate players/characters; the Cambion, Dryad, Erinyes, Harpy, Medusa, Rakshasa, Succubus/Incubus, Vampire, and Yuan-Ti Pureblood are all either depicted as sexy or have powers of enchantment that play on heroes' sexual attraction.

The D&D vampire, in particular, draws directly from Bela Lugosi's elegant, gentlemanly vampire - a portrayal fully embraced by 2023's Baldur's Gate 3. Everyone's favourite vampire twink Astarion is clearly a monster - a conflicted one to be sure, but a monster who feeds on people nevertheless - and his monstrosity can be further stoked by the player if they so choose. "Baldur's Gate 3 needed a guy who could convince you that murder is fine as long as you look hot doing it," writes PC Gamer's Tyler Colp about the blood-sucking minx. And of course, if you delve into Astarion's story, you'll find a terrified man who - well, let's just say queer people might resonate with parts of it.

As a German Expressionist film, Nosferatu was condemned by the Nazis as "degenerate" art. Yet my students basked in its supposed degeneracy, easily absorbing themes of sexual repression, desire, and homoeroticism. In a sense, they were all monster-fuckers, seeking to insert themselves into the moist, fertile, crevices of the queer, anti-authoritarian monster that seeks to disrupt the status quo and upend what is considered "right" and "moral". So I say yes, bring on the monster fucking! Bring on Venom's enormous, flexible tongue, King Shark's thicc himbo goodness, Pyramid Head's almost Grindr-like faceless abs, and Feyd Rautha's psycho, black-toothed, shiny-scalped violence. Let queers explore their anxieties, their transgressive desires, and their weird joie de vivre through unbounded sex. Let us love our monsters!