Full Steam Ahead: How Valve's Platform Just Gets Hotter

As Steam expands its services, EG looks at where it came from and where it's heading to.

If you want to know where Steam began you have to look at Team Fortress, and then you have to look at Microsoft. In early 1999 Valve released Team Fortress Classic, a Half-Life mod based on a Quake mod, and watched it sustain and steadily grow a player-base second only to Counter-Strike. It was a great game, sure, but what seemed to make the difference was its ongoing development in the form of regular updates. In those days, updating was a pain from a player's perspective. An inconvenience at best, at worst you wouldn't even notice any given release had happened.

At the same time as the developers of Team Fortress were looking at these problems, there was a growing awareness within Valve of how remote the company was from the people that bought and played its games. Speaking in Edge, Gabe Newell explained it thus: "We wanted a way to sell games, provide support, communicate with customers and get a better handle on what people were doing with our products in a way that would allow us to make better games. Nobody was building the system we needed, so we had to build it ourselves."

This article isn't about Microsoft, but it's worth saying that this is what Games for Windows Live should have been over a decade ago. Microsoft should own the PC games space - instead it's hopelessly behind. The idea of GFWL as a Steam competitor is laughable, and it's pinning all of its hopes on the closed system of Windows 8's app store. And thank god. In Steam, Newell's old employers inspired the kind of product it could never make.

Steam began as a way to get updates to players of Valve's games with the minimum of hassle. It launched in 2002 as this auto-updating system, and the first game offered for sale was Half-Life 2 in 2004 - a launch that had its fair share of problems. Rag Doll Kung Fu earns a place in history as the first third party game sold on Steam (2005), and successive years have seen a rollout of features like cloud saves and community tools. A beta of new community features is currently live, and will be accompanied in short order by Big Picture mode and Valve Greenlight.

The thing to bear in mind about Valve and why it makes things is its scientific approach to customers. So many companies pay lip service to the idea, but Valve directly builds things based on what the data is telling it about player behaviour. It is a reactive company, and this is Valve's most pioneering characteristic.

"In a nutshell, Windows 8 may be very bad indeed for some third parties. And Newell's not alone in thinking this, with folk from Blizzard, Mojang and Stardock among those with reservations."

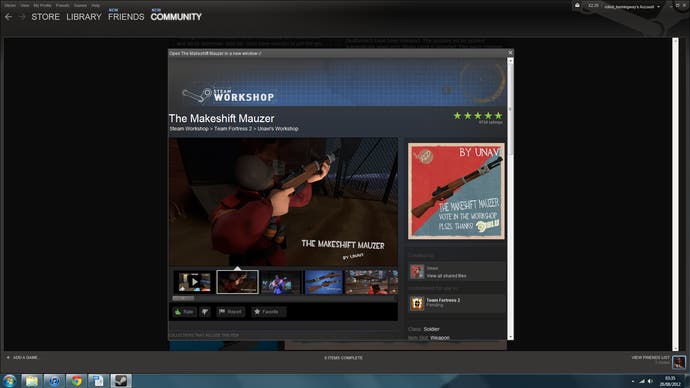

Everything comes from it. Valve Greenlight, to be launched at the end of August, hard-codes it into Steam's operation - this lets developers put up screens, trailers, and eventually demos to gauge interest from the community, and users to vote on whether they want to see it on the service. The Big Picture mode, shortly entering beta before a full release, is simple and deadly - essentially a redesigned UI to make navigating from the couch, perhaps with a wired Xbox pad, incredibly easy. It's not quite a direct competitor to what the console boys do just yet, but it undoubtedly brings Steam a step closer to the living room.

The new community hubs are in a sense the death of the fan-site. These gather everything you'd want around a particular title into one place: forums, news, community content, screens and videos. You can see this will be of spectacular benefit to community creators using the Steam Workshop to make new items (the very best of which stand a chance of being incorporated into the game 'proper'). And the whole thing is moderated by the community. Of course it is. The early days have seen the rather distasteful spectacle of front-page coarseness and nudity, but there's less every day as people figure out en masse how to get rid of inappropriate stuff and get deserving material up top.

The biggest new feature has nothing to do with games. From September 5th, Valve will begin selling non-gaming applications - so anything from Fraps to Scrivener. These will hook into both of Steam's great strengths as a gaming platform - more or less instant updates, cloud saves - and surely also the new community hubs, a marriage of practical software and support that seems so obvious you wonder why it hasn't been done before outside of gaming. This has the potential to make Steam's audience explode beyond players. Everyone knows folk who have bother installing simple applications on their PC, nevermind keeping everything updated. In the future, I'll just install Steam for them, set up an account, and expect fewer phone calls.

"The big question for Steam's future is a philosophical one. Steam is as open a content-delivery platform as you're ever going to get, and it will soon be competing in a PC space where the vast majority of customers are locked into closed systems from the moment they boot up."

Which brings us back to now, and where we started. Microsoft is pushing Windows 8 hard, because it is a company that lacks a strategy and is instead copying Apple's lead until it comes up with one. The Windows 8 app store is a worry for many developers, not least because it will have an instant monopoly over a huge proportion of PC users. This is one of the reasons Gabe Newell, speaking at Casual Connect in Seattle and reported on by AllThingsD, said "I think Windows 8 is a catastrophe for everyone in the PC space. I think we'll lose some of the top-tier PC OEMs [Original Equipment Manufacturers], who will exit the market. I think margins will be destroyed for a bunch of people."

In a nutshell, Windows 8 may be very bad indeed for some third parties. And Newell's not alone in thinking this, with folk from Blizzard, Mojang and Stardock among those with reservations. It's worth pointing out in this context, however, that Microsoft's intention to keep 30 per cent of an app's take and then 20 per cent after $25,000 revenue is slightly better and then much better than Valve's flat one-third (though this is an imprecise figure, it's the one always quoted by Valve and third-party devs).

The proof will clearly be in the pudding, but Windows 8 was one of the reasons cited for Steam now supporting Linux, described by Newell in terms of "a hedging strategy." Another niche covered. But the big question for Steam's future is a philosophical one. Steam is as open a content-delivery platform as you're ever going to get, and it will soon be competing in a PC space where the vast majority of customers are locked into closed systems from the moment they boot up. This is already the case with any Apple OS, and soon the same will be true for Microsoft. And all indications are that the wider public don't care about whether a system is open or closed, or which one's better in the long run, as long as the thing's convenient to use.

So maybe it'll take them head-on. John Walker put down his thoughts on a possible SteamOS at RockPaperShotgun, and it's a convincing possibility. As Walker points out there are plenty of issues (like Steam's 'offline mode'), but none are insurmountable.

"Steam began as a solution to a problem, and then Valve just kept on solving more problems with it."

A Steam operating system is a dream future. It would also be a defining moment for Linux itself in terms of reaching a wider audience. Would Valve do it? It is a company that is impossible to pigeonhole, but this would change it irrevocably: from something like a third-party developer, publisher and supply chain to something like a direct competitor to Apple and Microsoft. The consequences of this could be catastrophic, because it takes a massive gamble on both Steam's current position and its current installed base.

I personally don't think SteamOS is likely, and lean more towards the less exciting prospect of someone Kickstarting a Steambox. Well, it's still quite exciting. It's likely that the Steambox rumours from last year were based on Valve demoing Big Picture mode because, as with Steam itself, Valve wants others to take the opportunity first. A very recent G4TV episode has great access, and the whole thing's worth a watch. When asked if others making the 'Steambox' is the preferred option, Newell answers - "That's what we hope. We show hardware guys and say 'well if this is a useful tool for you to deliver your hardware in the living room, that's great.'"

One small step, perhaps. But that's how you get places. Everything about Steam has been small steps, from something as simple as selling Valve's own software to opening up the company's toolset for third parties. And then some kid in Kansas makes $150,000 a year selling hats and no-one outside of Seattle is quite sure how that happened. Steam began as a solution to a problem, and then Valve just kept on solving more problems with it - identifying what users say they want, responding to trends in player behaviour, making the things people are doing anyway that much easier. Steam's future isn't planned out. There's no secret roadmap at Valve HQ. Where Steam's going, and how it changes, depends on what players want it to do. Whether they know it or not.