Games of 2012: The Walking Dead

It's all gravy.

Every year or so a game comes along that makes me recalibrate my notion of how the medium can tell stories. Uncharted 2 proved to me that the traditional model of cut-scene-gameplay-cut-scene actually can work if both parts are expertly crafted and don't outstay their welcome; Demon's and Dark Souls proved to me that a cohesive, yet mystifying world can work as well as any conventional plot' and The Walking Dead proves to me that the choose-your-own-adventure-movie format can actually work for a full-length game.

Of course this template has been attempted before. David Cage's Heavy Rain comes to mind, but I've always chalked that one up as a failed experiment. I found it had more plot holes than plot, most of its interactions felt like unnecessary gimmicks (brushing one's teeth, for example), and the chapter-select feature encouraged players to go back and make different decisions with the ultimate goal of getting the 'good' ending, just as we kept our finger on the choosy pages in those choose-your-own-adventure books all those years ago.

Telltale's Walking Dead does away with the finger. We can't bookmark our progress, copy our save data, or rewind our story via a chapter select (although you can quit the game and resume at the last checkpoint, which I would argue is missing the point entirely). We must live with our consequences. If you want to see what else might have happened you'll have to start a new game - which you're not going to do as it's pretty long - or you're going to accept the hand you've been dealt and move on. You can trade war stories with your buds later.

Perhaps more revelatory, The Walking Dead challenged my perception of a game by proving less interaction can often make you more engaged. People may call The Walking Dead a point-and-click adventure, but that's an erroneous claim based on our limited vocabulary for game genres. There's very little in the way of puzzles, and what tiny bits there are could - and probably should - have been omitted. A vast majority of its interactions are saved for key moments like picking dialogue or actions. You decide the important stuff: who gets to eat, who to save, and whether to lie to various people. Otherwise, the game largely plays itself out. There's no teeth-brushing, in other words.

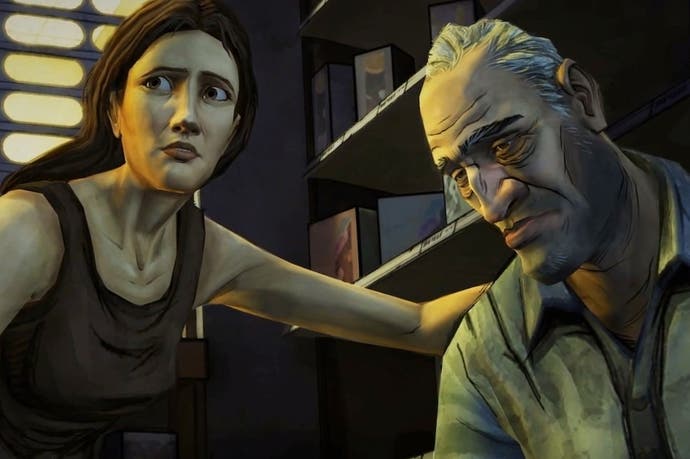

The lack of agency is crucial to The Walking Dead's success because it has to walk the very fine line between, on the one hand, making protagonist Lee Everett an established character with his own personality and history, and on the other hand making him a cipher malleable to the whim of the player. Usually when games allow us to create our own character we end up playing as some boring dolt who only has whatever traces of a personality we instill in him or her, making them about as interesting as talking to yourself in the mirror. Either that or they have defined identities that quickly break character because the person controlling them makes them do silly things like run around in their boxer shorts or hop on people's heads.

Lee is different. Lee is his own man most of the time. He's a kind, loving soul tormented by feelings of guilt after his anger issues and brute strength got the better of him, resulting in the murder of his wife's lover. Comparatively, my Commander Shepard was nearly perfect. He lived his life mostly picking blue "Paragon" options and everyone loved him. "I guess you're right," people would often say to him, followed by an overt exchange of smiles, just in case there was any doubt that you weren't totally awesome at everything you did. Lee was human, though. Like most people, he wanted to do good, but was capable of evil. He's sympathetic, relatable, and, most importantly, fallible.

So how does Lee peacefully co-exist with the player controlling him? Simple; we only influence him when he's making very difficult decisions. The way people act under pressure often bears little resemblance to who they are ordinarily. I discussed core decisions with several friends after each episode and was surprised to learn my devoted family man pal made a grieving father shoot an undead child, while my disaster relief worker friend let a mopey teenager die because he was a liability, and others questioned my mental state when I killed a man who hadn't yet turned, but was totally going to... Probably. The point is we all had valid reasons for why we did the things we did, unpopular though they may have been. Reasons Lee would have considered.

The sharp script masterfully wraps its choices around a single, only moderately branching narrative, yet it never feels like your decisions don't matter. The outcomes may be similar, but your relationships with the cast alter, which in turn changes your perspective. I knew people who hated Kenny and considered him a psychopath, yet in my game I was sympathetic to his plight and he reciprocated my kindness in turn. It doesn't matter that his ultimate fate is largely prescribed. What I felt for him changed based on our budding bromance and this lent itself to some exceptionally powerful moments later on.

Earlier this year the industry was up in arms over the ending of Mass Effect 3. Players cried foul at its conclusion, commonly stating that it dropped the ball because "your choices didn't matter". The Walking Dead proved that your choices not affecting the final outcome wasn't the problem with Mass Effect 3's denouement. It was just bloody stupid. The Walking Dead doesn't give you any more control over the outcome, but this is to its credit.

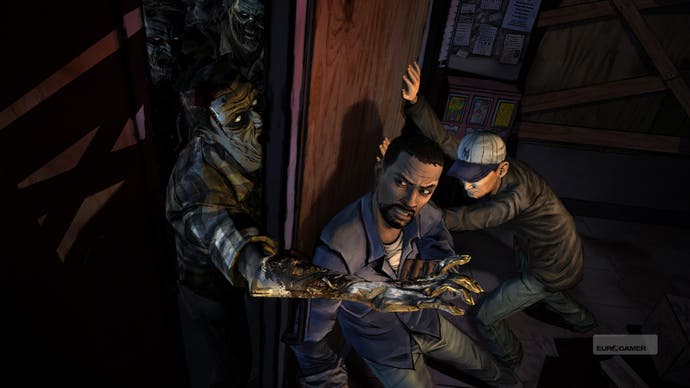

Generally games are little more than a set of challenges and win conditions; slay the boss, attain the high score, or pick the right choices until you can live happily ever after. The Walking Dead doesn't let you win. Sure, you can get to the end credits so long as you pass a few quick-time events (or reload them until you succeed), but there is no 'good' ending. There's no conventionally 'bad' ending either. Everyone's fate ranges from bitter to bittersweet and you're powerless to stop it, just as Lee is but a tiny spec of matter in this corrupted universe. There's no saving the world here. The best you can do is put a band-aid on it and hope it doesn't slide off, no matter how gross and slippery it may get.

The Walking Dead's brutal, unflinching look at the zombie apocalypse was also a strict wake-up call at just how mollycoddling most games have become. Earlier this year I played through I Am Alive, a dark gritty post-apocalyptic game in which unfortunate women are kidnapped and ostensibly raped in a hotel run by bandits. It was very grim subject matter, but the game skirted around the issue by refusing to show nudity or even say the word rape. You might argue that a survival game can't deal with such touchy subjects in a mature way (and Square Enix would agree with you), but bringing up such ugly issues only to portray them in a manner suitable for network television is too nebbish to make an impactful statement.

Upon starting The Walking Dead shortly after, I found the first episode appropriately melancholy, but had doubts that it would go so far as to contain say, child zombies. Not only did it have undead minors, but, depending on your choices, you may have to be the one to put them out of their misery.

Beyond its innovative design, The Walking Dead might be the first episodic series to really justify the format. As much as I admired Telltale's work on Tales of Monkey Island, I found its constant starting and stopping hurt the flow of the adventure and limited its scope, while Valve's attempt at serialising Half-Life has long been a joke. The Walking Dead worked much better, probably because the choices were so difficult that people felt compelled to compare their results. Since the game was released over the course of seven months we all had a chance to catch up with each other and excitedly discuss not only what happened in the last episode, but what we were looking forward to as well, since it was usually right around the corner. Generally when a game comes out we all gorge on it until the zeitgeist passes and we're on to something else in a fortnight, but The Walking Dead permeated my social circle all year as late adopters would catch up, eager to share stories and speculate.

Most of The Walking Dead's accolades have stemmed from its writing, and for good reason; its sophisticated script is laden with realistically understated characters, morally complex situations, and an unflinchingly sombre tone. But that alone wouldn't have been enough to justify its existence as a game. Telltale already made that mistake last year with Jurassic Park. That project also had a smart script that would have made a pretty good movie, but it was ill-fit for a game. It mistook wasting the player's time with exhausting dialogue trees and clumsy puzzles as agency and ultimately ended up marginalising - and boring - the person holding the controller.

The Walking Dead is a vast improvement over the failures of the past thanks to the discovery that fewer, more meaningful interactions trump lots of filler. For once the player and author can spin their tale harmoniously together in a way many have tried, but few have succeeded.