Video games in China: beyond the great firewall

On the ground in the vast world of Chinese gaming.

Video games are a small window into Chinese life, but they're a window nonetheless, and video games themselves, in China, are huge. China accounts for more than half of the entire planet's PC gaming revenue. In fact, despite it being smaller than mobile gaming there, China's PC gaming market alone made over $15bn in 2018; more than half the entire amount of revenue made in the US gaming industry overall, including consoles, mobile, the lot. Going by the numbers of analyst firm Niko Partners, as of 2018 there were a total of about 630 million gamers in China - a little over 8 percent of humans on the planet.

Huge. But we know there are lots of people in China, and we know lots of them play games. What's really interesting is that these people are playing games in what is, on paper, the most aggressively censored system around. I suspect this sort of thing is why economists love visiting China, even if doing so is a risk: everything is a case study.

Games are no different. Under Chinese law, video games can't contain anything that "threatens China's national unity, sovereignty, or territorial integrity". They can't harm "the nation's reputation, security or interests". They can't promote cults, or "superstitions". They can't "incite obscenity, drug use, violence or gambling" - although loot boxes are, of course, fine (in fact Niko Partners analyst Daniel Ahmad reckons a Chinese game may have invented them as far back as 2003) - and they can't include anything that "harms public ethics" or China's "culture and traditions". They also can't include any "other content" that might violate China's constitution or law, whatever that may be, and they have to be published in China by a Chinese company.

There are no definitions or examples of case law provided for any of those remarkably loose terms, of course - no precise legalese in paragraph 13b. How those rules are interpreted is purely at the discretion of the committee, which, by now, we've seen in action time and again. Shenmue 3, for instance, is set in China, but as a recent trailer showed, developers Neilo and Ys Net changed the names of locations in the Chinese version from real Chinese cities to fictional, non-Chinese ones, likely so they steer clear of that part about Chinese "culture and traditions". More dramatically, Monster Hunter: World was due to launch on Tencent-run WeGame in 2018, until it failed to get a license and was ultimately pulled from sale altogether.

"Let me tell you, it's a fucking fortress."

Mike Rose, No More Robots

There's no ESRB or PEGI to act as industry self-regulators (although very recently it's looked like there might be an equivalent in the works) meaning some government-linked mega companies, like Tencent, are wise enough to "self regulate" in their own ways instead: policies like forced age registration when you sign up to play their games, for instance, enable them to place two-hour time limits on children's gaming sessions. As things stand though, there are no age brackets or classifications: just that catch-all set of rules that show a government at peak paranoia.

Censorship is bleak - and far bleaker, of course, when it moves beyond video games to the day-to-day - but there's a certain Scunthorpe-problem irony to how it really works in practise. To take the most pertinent example, the government in China has tried to block anything on the internet pertaining to its massacre of citizens at Tiananmen Square. Its date, June 4th, is obviously blocked online, but so is May 35th, a made up date used by those determined to preserve its memory. And so, according to a fascinating podcast from The Economist, is every instance of the word "today", as the anniversary nears each year. When it comes to video games things are just as absurd, only they're absurd for a different reason. Where bravely pro-democracy activists are dreaming up new dates and words to dodge the censors, Chinese gamers are just downloading Steam.

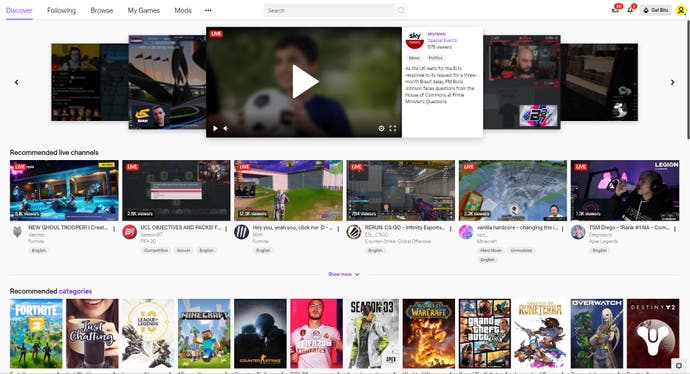

Vanilla, international Steam, or "Steam global", is openly downloadable in China, with all of the games available here in the west (apart from especially pornographic ones, curiously) unblocked and ready to go. The only other thing on Steam that's blocked in China is the community section, which just comes up with a blank, Steam-grey page if you try to access it, like your internet's cut out or a server's gone down. Aside from that you can buy, download, and play games on Steam global, in China, exactly as you do anywhere else. I even tested it out for myself, with Hong Kong-set Sleeping Dogs, on standard hotel wifi without a VPN or anything like that, and it worked as it always does. You can download games you've already bought, load up saves you've already made elsewhere, and browse the store's array of games at will. The works. The result is Steam, as it currently stands, is now widely known as a great, big, gaping hole in the otherwise impenetrable Chinese firewall.

The reason it's really taken off, though, is 2018's game approval bottleneck. Games get released in China by being submitted to a committee called the SAPP, which is the body that checks it against those rules mentioned above. The committee can take months or even years, in some cases, to decide exactly whether or not a red smudge looks like a pool of blood. (This is an actual issue that was flagged to the developers of Risk of Rain 2, by the way, who are changing an icon's background from a red smudge to something else in order to pass approval. "Some of the backgrounds of the tier 3 items are red, which kind of looks like blood?" Paul Morse, co-founder of Hopoo Games explained to me. "It's not, but, we'll change the colour a little bit and that's super easy for us." That, or "maybe so it looks like lightning or something," added fellow co-founder Duncan Drummond).

The bottleneck came when the approval process itself ground to a halt altogether, for more or less the length of 2018, for the rather fitting reason that two different regulatory bodies had argued themselves into deadlock over how best to monitor the nation's playtime - until the government got fed up and merged them into the current one. With nowhere else to go for new games of any kind, more and more Chinese players sought out Steam, and the platform's Chinese playerbase spiked to around 30 million, doubling in the space of that year.

"There's a certain amount of fly-by-your-pants to this whole industry..."

Matthew Davis, Subset Games

Now the SAPP is up-and-running and approving games again, but still serving the same purpose of funneling gamers towards playing via more illicit means - and still making it incredibly difficult for foreign game makers to navigate through. I spoke to a lot of developers and publishers about it but Mike Rose, of No More Robots, the publisher behind games like Hypnospace Outlaw and the upcoming Yes, Your Grace, said it best: "Let me tell you: it's a fucking fortress. In the last year I've got nowhere." Even if you were to get approved, he said, the share of revenue Chinese platforms ask for nears 50 percent.

So players head to Steam, and the government, so far, just doesn't seem to care. The huge blind spot is surprising, to say the least - but more surprising still is that the government isn't just turning a blind eye to Steam; it's turning a blind eye to gaming in China as a whole. For all the talk of harsh censorship in games, and president Xi Jinping's desire to "care for the children's eyes" and protect their "bright future", the lack of meaningful enforcement of those rules is striking. Tell that to Monster Hunter: World, you might be thinking - but that's just one incident, on the surface. Dig just a little deeper and there's a world of gaming in China where it can feel like the regulators just don't exist.

"The place to look for console gaming," says Kotaku, way back in the late last-gen era of 2013, "is the grey market".

Back then, in the days before online retail crushed the physical shop and prior to Steam's real explosion of global popularity, the Chinese grey market meant cybermarts. These brick-and-mortar department stores were blatant even then, where console gaming was banned outright, but then in those days there was still the excuse of China being vast, and regulating physical places en masse would have likely seemed just about impossible. What's astonishing is that even in 2019, where everything from the internet's deep-mind, AI-driven firewall to towers of facial recognition cameras in the streets means China's sheer size is no longer an obstacle, the authorities have no interest in closing these grey markets down.

The cybermart on Huaihai Road, a busy, relatively up-market hub in Shanghai, is a perfect example. It was mentioned by Kotaku as a great spot to buy games in 2013, and even further back, in 2008, as a black market "eagerly awaiting" the new iPhone. It's an open secret - even my translator knew the spot - and it functions more or less as any other department store would in the light of day, with a disinterested police car parked not two doors down.

As Niko's Ahmad, put it to me: actually buying and selling games that directly contradict government regulations is "a grey area... it's not illegal in that you won't go to prison for it, or get fined for it, but it's something that the government wouldn't want to happen." Inside the Huaihai cybermart you'll find a wall of Xbox consoles and games, that looks just as any featured wall would in your local GAME or GameStop, while tablets and laptops are laid out on white, underlit tables, like you'd find them in PC World.

Move a little further inside and the "grey market" trappings that you might expect become a little more obvious. At the back of the ground floor is a pair of gaming shops, occupying small alcoves in the back wall, obscured from view from the entrance. At the time of my visit, one of them was in the middle of a shipment, so to speak, unloading several large cardboard boxes filled with special editions of Fire Emblem: Three Houses directly into the front of the shop. Standard copies, marked as Middle East and Southeast Asia versions, sold for roughy the same price as they would in the UK (400 RMB, which translated to around £43 at the time), and despite advice to the contrary and my own attempts (or maybe because of them), there was no room for bartering.

It was maybe a little quiet, during my visit - the floor was almost entirely empty of customers, although it was in the middle of a working day - but it's hard to say the rush to Steam has had an impact. There's far from an air of brick-and-mortar-decline, and if the Huaihai Road cybermart is anything to go by, the sense is that the physical, grey market shop in China is doing just fine. Although, Steam isn't the only rival jostling for position in the grey market. There's also Taobao.

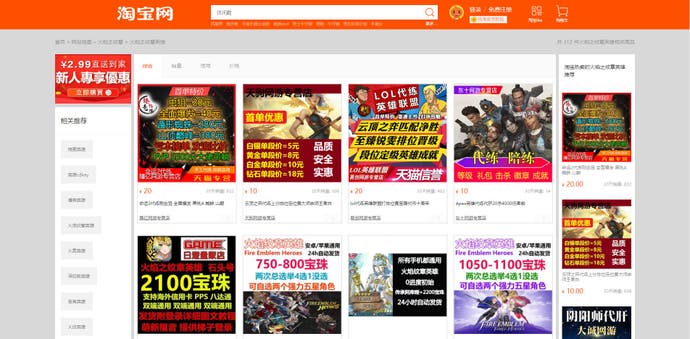

Taobao is a vast online retailer that operates as something of a hybrid between eBay and Amazon. It actually outranks Amazon by some way, in terms of sheer website traffic, and for many gamers in China it's now the physical grey market of choice. Most local gamers that I spoke to would use Taobao to buy their physical games, rather than a high street store, albeit for different reasons.

"I'm not from Shanghai and so the ways of getting gaming is too limited," Yao, a Chinese gamer in town for the International, told me, "so maybe in Shanghai you can get the games offline from shops, but I'm not from there, so I would just get the games from Taobao."

Others use it because, being a kind of peer-to-peer platform, you can buy and sell games second hand for close to the original price. Jingling Lou, a Shanghai local who mostly plays on Nintendo Switch and, full disclosure, acted as my translator for some of the week, told me she'd only lose "maybe 15 RMB" between buying and selling a game - buying for £35 and selling for about £32.50 - and that when it comes to buying physical game cards it's "always from Taobao".

What makes Taobao interesting, though, is that it's also attracted a little more attention from the government. Regulators have actually issued edicts to Taobao in the past, asking them to refrain from selling unapproved games. In 2017, Taobao was even banned from selling imported games altogether, but, again, it seems to have had little effect. As China-based technology website TechNode reported at the time, "some Taobao sellers have said they don't know how to follow the new rule because they haven't been given specific details." Whatever the reason, imported games are still available there now.

All in all, video games' story in China has been one of awkward, undeniably market-altering regulation, but also one of questionable actual effect. The stated intention behind it all is that, from damaged eyes to weakened morals, games may harm citizens of China in a variety of ways, and so they must be strictly regulated to bring that hazardous slide to a halt. But the end result is almost the opposite: a distorted, unregulated market, where anyone of any age with a credit card can buy just about any game on Steam, or Taobao, or at a department store down the road, with little trouble. It's astonishing that the government still allows it - which brings us to Steam China.

Steam China was announced in 2018 and immediately followed by more than an entire year of silence. We know Valve, based in Seattle, Washington, USA, is partnering with Perfect World, based in Shanghai, China, to make a dedicated, officially sanctioned version of Steam for the Chinese market. We know the two have partnered before, with Perfect World publishing the hugely popular Dota 2 and Counter Strike: Global Offensive for Valve in order to get around the foreign game restrictions - with modifications made to pass approval, of course.

"If you ask any analyst, we'll always tell you we're surprised this hasn't happened years ago."

Daniel Ahmad, Niko Partners

(This is why rival company Tencent publishes League of Legends for Riot Games, by the way, and Playerunknown's Battlegrounds - or Peacekeeper Elite, to give it one of its Chinese names - for PUBG Corp. It's also partly why publishers are probably less concerned about that chunky stake they sold to Chinese shareholders than you'd think; it's a way to help sell their game to a huge part of the world).

Other than that, though, we weren't given a lot. A press release, back when it was announced, told us Steam China "will provide Chinese gamers and developers with a new way to access Steam's expansive selection of games and entertainment," and that Perfect World will "introduce more games to China through Steam China, providing quality content and improving the experience for both gamers and developers." Another fourteen months go by without a peep.

Then, all of a sudden, Valve invites the press to a Steam China event in Shanghai, under the guise of covering The International. The expectation at the time, given the fact Valve was flying journalists around the world to be there, was that this was going to be a significant announcement. The reality is a near pitch black basement with a stage, somewhere deep in the bowels of the colossal Mercedes Benz Arena, where Perfect World CEO Dr. Robert H. Xiao told a handful of Chinese tech journalists that the two companies are "one more step closer" to launching Steam China. "The Steam China project is undergoing solidly and smoothly," he says. There's a sizzle reel of a couple dozen games that are coming some time or other, and that's that. Still no release date, or release window, or release year. Still no look at the UI, or talk of any real features (barring official local servers, which is a given).

What's more, despite plenty of reports to the contrary, there's also still no actual, official list of launch games either. The number doing the rounds is 40 - not exactly the 30,000 or so that are available on Steam global, at the time of writing - and that 40-odd is made up of mostly Chinese-developed games with a handful of foreign ones (FTL, Into the Breach, Risk of Rain 2, Euro Truck Simulator, Two Point Hospital, Descenders, Overcooked 2, Abzu, Saubnautica, Stronghold: Warlords, and Absolver, to be precise). Matthew Davis, of FTL and Into the Breach developer Subset Games, told me Into the Breach hasn't even been localised into Chinese yet, meaning there's no way it'll be ready for Steam China's launch as things stand. No More Robots' mountain bike racer Descenders has to remove "a bit of comedy violence," according to Rose, "when you have a crash, and the guy goes "oeurgh!" ...some crunching bones" before it can even go to the approvals stage. Hopoo Games has "five points" that need tweaking in Risk of Rain 2 before it can be submitted, "which is really really good" - a list of just five small tweaks is apparently pretty small.

In fact, not a single foreign developer or publisher that I spoke to - in the room where snazzy, Chinese-audience-appropriate versions of their games had just been flaunted as a key selling point of the platform - said their game had even made it through the approval process yet. It's not clear that any of the Chinese-developed ones had either. None of them, foreign or domestic, openly committed to being there on launch.

Such an air of obfuscation there was at the event, Valve wouldn't even tell me whose idea Steam China was, or when the company decided it needed to do it, or even really why it's happening: "I don't know the genesis ... It's just gonna be a much better experience for Chinese customers ... We want Chinese customers to have really high-quality access to steam games", DJ Powers told me. It's not a slight on him - I honestly think he was being as candid as he could, all things considered - but in terms of the actual purpose, or progress, of Steam China there was effectively nothing to be learned from the event.

Being frank, it's hard to know exactly what's going on. To go back to Daniel Ahmad, he reckons "it's just so that Valve can have an official presence," so they can avoid "any push back from regulators or from the government, essentially." It's hard to disagree, but either way Ahmad reckons there's "definitely" been at least indirect pressure from the government to make things official. Valve, perhaps understandably, wouldn't say.

Steam China's purpose, though, is largely secondary. The real question, when Steam China does eventually go live, is what will happen to Steam global. In the last six to twelve months or so Steam's Chinese audience has risen from 30 million to 40 million, meaning with Steam's total audience somewhere between 90 and 100 million, China alone is getting close to counting for an entire half. It's growing, and rapidly, and that's the thing that makes it stand out from Taobao or your local cybermart: if recent examples like the rapid rise and ban of Twitch in China are anything to go buy, the government is much more likely to intervene when large, potentially culture-shifting western platforms gain a sudden popularity - especially amongst the young and impressionable. The probability depends on who you talk to - the gamers I spoke to were largely optimistic, quoting local news to me, which had apparently reported Steam global will be fine - but as things stand there is every chance that, when Steam China goes live, Steam global gets blocked, and those 40 million Chinese gamers aren't the only ones who stand to lose out.

For a while, it's just been the big, obvious games that would be affected if someone in China were to suddenly pull the plug. Giants like League of Legends and Dota 2, of course, rely on Chinese players for huge chunks of their audiences, but it's fair to say that for most, those kinds of games are often ignorable: often they're either all you play, or you don't play them at all. If they're not your thing - and if you're not one of the people making them - then there's been no real reason to worry about what goes on in China.

Now, even if you've never touched a mobile game or a MOBA, that's no longer the case. Chinese players make up "20 to 30 percent" of No More Robots games' audiences, for instance. Gearbox publishes Risk of Rain 2, which is in early access, and their representatives out at the Steam China event told me the Chinese audience is "just destroying everything else... after two weeks it was our number two seller", behind only the USA - and this was before they'd published a Chinese localisation. Pawel Sebor, CEO of SCS Software, which develops the Truck Simulator games, again said the same thing: "Even though we have a niche game in weird genre, China is a top 5 market for us" - and it's not like there's a China Truck Simulator, or at least not yet. As Sebor put it, if Steam global was blocked and the Euro and American Truck Simulator games weren't able to get onto Steam China, the simple outcome is they would lose "quite some percentage of sales".

It's worth noting these are all games that are planned for Steam China, and so are naturally going to be a group that's especially popular there. But there are others that aren't, like Total War: Three Kingdoms and Football Manager, that still rely on huge Chinese audiences - and there's still that userbase of 40 million to think about. More than enough to worry about if the lights suddenly went off.

Subset Games' Davis, for whom Chinese sales again make up about 20 percent, is pretty philosophical about it. "There's a certain amount of fly-by-your-pants to the whole industry, that I regularly find surprising," he told me, "and so you just learn to roll with it and see what happens." Ultimately, even if publishers and developers of all shapes and sizes rely on China for a good chunk of their profit, there's a chance they'll have to find a way to cope without.

The actual chances aren't clear. Speaking to Ahmad here in the UK, he was hardly effusive when I asked him about Steam's chances of staying live after the launch of Steam China: "It's hard to say... if you ask anyone like myself, or any analyst, we'll always tell you that we're surprised that this [shift to the official Steam China] hasn't happened years ago. Because the signs have always been there that it would - so this actually happening isn't a surprise, the surprise is just that it's taken this long."

"Whether Steam is shut down or not, what I will say is Chinese players will still find a way around it, whether through VPNs or whatever method, just because people invested a lot of time and money into that platform, and so they want to retain their existing library but also play these new games."

China's fascinatingly tangled economy has even adapted to that very problem. There are companies - big, official ones, like Netease, which sits on the board at Bungie and owns a stake in Quantic Dream - that provide tools to circumvent blocks or bans, and even speed up your connection to online games with foreign servers. It reminded me of what my translator Jingling said to me, in my final conversation in China: "If they close Steam they must have a very good excuse - otherwise all the gamers are going to do something about it."

As hopeful as that sounds, there's every chance she might be right. Chinese gamers have learned to adapt, just as developers everywhere have learned to roll with the punches, and there's a sense of rising ingenuity, too, to a market warped by uneven regulation. The only real certainty, though, is that the global industry at large and the fate of video games as a Chinese pastime are now inextricably linked.