George Fan, creator of Plants vs Zombies, on design and his new game about the greatest fact in the world

And whether three months is enough time to ruin a friendship.

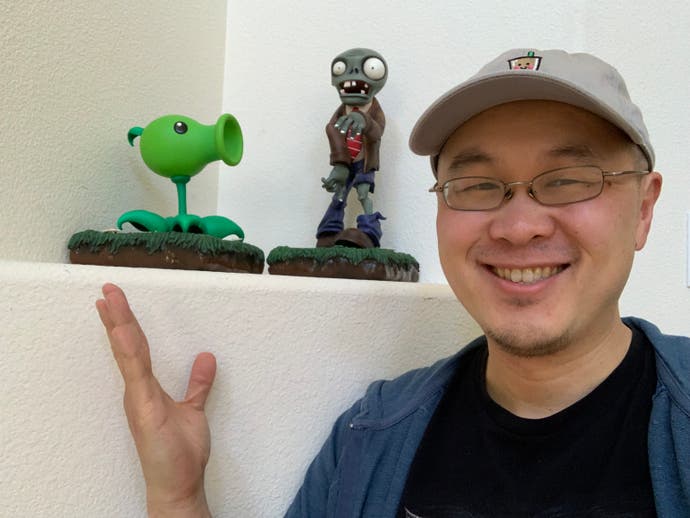

George Fan is the creator of Plants vs Zombies, alongside fascinating, playful, elegant games like Octogeddon. He's also seen as having created the best ever GDC talk, "How I got my mom to play through Plants vs Zombies." It's a beautiful bit of applied thinking about game audiences and tutorials.

More recently, he's been working on a game called Hardhat Wombat. I've been playing a build for the last few weeks and it's as elegant and interesting as ever. You play a wombat construction worker who must build various structures from - well, I'll let George explain that.

With Hardhat Wombat launching soon, I got to chat with Fan about his work in games, his early doubts, and why he likes to build projects around game jams.

I came to visit PopCap in Seattle once when Bejewelled Twist was launching. They did a huge press thing at the EMP centre by the Space Needle. It was a really interesting time to visit because at the same time as Bejeweled was getting this fascinating sequel, they said to me, "Oh, we've got this other game, which we're really excited about. Do you want to see that?" And it was your game, Plants vs Zombies, which I think at the time was still called Lawn of the Dead.

George Fan: For that event, I think I suggested to them that they should have Bejewelled Twist [in real life]. They should have people sit in tables of four with lazy Susans on them. And they bring your order, you know, fish or chicken for dinner. They bring that out and then midway through dinner, someone would say "Twist!" and then you get someone else's meal. No one took my idea.

See, that's particularly interesting because I read once that at the start of your career you were uncertain whether you could be a game designer. With the lazy Susan thing it feels like maybe you should never have been uncertain at all? But I am interested as to why you once felt like that?

George Fan: In my very early days of game design? Yeah. Before I figured things out. So before getting into game design, I was an artist. And being an artist is like: you see the image, you see the canvas in your mind, and all you have to do is just translate that image to paper or whatever medium you're using, right? Yeah, I noticed that game game design was not like that. You just couldn't keep the thing in your head. I had this idea for a game that seemed really fun. We'll call it Cat-Mouse-Foosball. It's kind of like reverse-Donkey Kong. The cats and mice are like the barrels in the original Donkey Kong, they're both funnelling down in a zigzag, and then you have these foosball sticks that you would use to block off cats and mice. If cats and mice touch each other, the mice would get eaten. So you're trying to get as many mice down to the bottom as possible by blocking things off.

So I thought that sounded kind of fun. In my head that was like, yeah, this is a great game idea? I prototyped it and I tested it out. And it sucked. It was no fun at all. That that was my early days, and that's when I was questioning, you know: should I be a game designer? I think it's that you have these ideas, and you can't know if they're fun or not until you test them out. And moreover, games are a bunch of different moving parts. You just can't keep the whole thing in your head.

And I think the secret I've learned since then is, you can you start off with a core game concept. You test it, that's fun. And then for the rest of it? Just forget trying to design everything out in the beginning. You just have to iterate on things over and over again. And the more iterations you do, the better the game is. So I since figured that out. And I now I now feel like I can be a game designer.

Two questions from that. Firstly, is that just not true of the way you approached art when you were doing more traditional art? It wasn't iterative? You'd be like, I'm going to do it, and then it's done? Now, we hang it up, and that's it? And secondly, when? When do you think you learned this lesson? When it did it start to settle in: Oh, this is how this works, now.

George Fan: Art is: typically you spend a day on a piece. I think I was doing ten hours and I could have something done. So yeah, it was less iterative, I think. I mean, a lot of art, the mediums that you think of - I was working a lot on coloured pencil. But even with oil paintings, it's kind of hard to make huge adjustments. You have to plan it out in the beginning, do a sketch. And then when you're applying stuff, it's really hard to do much upheaval or changing things across the board. There's a time to experiment, and that's in the beginning. That's when you would iterate, maybe. Here's the picture I have in my mind, and I'm putting it on paper. It's all much shorter. It's a much shorter kind of event.

Whereas making a game can take much, much longer than that. A day for a game! Even game jams are two days.

And then when did I figure it out? I don't know if I figured it out for my first game. My first commercial game was was around that time actually, it was a little bit after. I started prototyping in Shockwave. It wasn't Flash, it was Macromedia Shockwave, which was what people were making games in that at the time. Perhaps I learnt it a little bit during making Insaniquarium. It was near the end-game of making that game that I started trying lots of other things out inside the game.

But I think I would say that for Insaniquarium, I think you can iterate and find that most of the things work, so you don't feel like you're iterating as much. I think it was with Plants vs Zombies where we really started trying things, and a lot of things just went to the cutting room floor. And I think it was around then when I heard someone, another developer, saying, "Yeah, games are all about iteration." And I think I always knew that deep down. When I started making games, it was all: "Oh, you write up a huge game design doc." And I don't think I've ever done that. So it was around then that I kind of figured out that's definitely not my style.

One last thing that leaps out. So you were used to making paintings or artwork in a day. And one of the things I often wonder about game design is that it takes such a long time and it is so iterative. With all that time and iteration, how do you retain that freshness that a sketch has? I don't know if, in your artists career, you've ever done a sketch and you're really pleased with it, and then when you try and turn into a full work of art, the immediacy of the thing and the dynamism doesn't survive that transition? I wonder how you keep the sketch-like energy with games?

George Fan: I have a pretty good answer for that. And it's that you should start your game off of a game jam idea. I think the other way to go about it is: Okay, kind of think of the beginning as a sketch. But I feel like if if you have all the pressure of, you know, this game has to be fun, this game is gonna turn into something big? I don't know if that's the best thought for fostering creativity that you could have.

I think there's something about game jams, where there's the right amount of pressure, that leads to a lot of creativity. I go into game jams thinking, I could just make the dumbest game and be fine. Like, sometimes I actually go into game jams trying to purposely make the stupidest thing I can think of. I think that's the equivalent of: you have 30 minutes to paint something or draw something. Go!

And so you have that end of it, but I don't think that end is enough. Then you have the other part. There's a little bit of a competition. There's no prizes or anything, but in the case of Ludum Dare there's ratings, and there is a ranking at the end. And even with Popcap game jams, even then there was no official competition, but you were showing your game to your peers. And so they would give you their reviews of it, their feedback on it.

So I think it's between those two things, and then a third thing, which is that game jams often give you a theme to work with. I think that trying to think of a game that adheres to that theme can lead to some really... it's like a pathway. Whereas if you just had a completely blank canvas, blue sky, I think you're actually a little bit less likely to come up with a completely new or creative take on something. And so yeah, I think I love game jams for starting things off. You have that weekend to nail the core gameplay.

Octogeddon started in a game jam, I gather. Did your new game Hardhat Wombat start that way as well?

George Fan: Yes, Hardhat started in a game jam. So both of these I think are 2013. Now that was a long time ago. Octogeddon was my first Ludum Dare game jam, and the theme was "evolution". So I instantly thought that I wanted something like an octopus that you could upgrade and things would evolve from that.

So Hardhat Wombat? This is kind of funny, this is the only time that the theme, I feel, hindered me. I love Ludum Dare themes. But this theme was the worst thing I've ever done. And they recently revisited this theme, and I had my weekend all set aside to participate. And then I was like: no.

It's usually that people suggest themes and they vote on it. And this time, the theme was "10 seconds". So I sat down and I was just brainstorming what what kind of game I could make. I landed on: you are a construction worker. So it's your sidescroller platform game, building these square girders and things. Except you had to take a lunch break and eat a sandwich every 10 seconds, or else you'd just starve, and game over, right?

That's the premise I was going with. I called the game I Need a Lunch Break! With an exclamation point. You jump from platform to platform, and then you'd have these blueprints that you had to fill, they'll be shaped like a pyramid or something. It'd be a template of things you'd have to fill in.

So the game was kind of shaping up, and then I added the 10 second thing. And it was just the worst. I was like, oh my God, what am I going to do? So I cheated a little bit, and I made it that at 10 seconds, you start panicking, and the sweat starts coming off your face. And then you have six more seconds to run to get to a sandwich station before you keel over.

But I think a lot of that game jam was spent wrestling with like: oh, my God, this game is not fun anymore. How do I make it fun again? So I actually didn't have time to do some basic things I would have. I didn't have time to iterate at all, at the end. So imagine that template, say it's like a pyramid. You had to put blocks in and line the blocks up in that pyramid. However, in the game jam version, you could leave blocks outside of that pyramid just fine. And so you can make basically a giant cube. Yes, that will cover the pyramid. Definitely. So that kind of that part always bugged me.

And I think I think I did okay in the game jam, but with Octogeddon I scored much higher. The other thing is I wrestled with, I think I'm a better game designer than a programmer, but I was wrestling with physics. Okay, I can make a bridge of blocks, and when I when I cut the two ends, the middle has to fall. I remember struggling with that a lot.

Those two things combined led to it not quite being the game jam I wanted It to be. And so I just let it stay like that for years.

What happened?

George Fan: One summer, maybe it was the beginning of the pandemic, I was just noodling around with, you know, what am I doing with this all this time? Okay, I'll revisit I Need a Lunch Break! And first I'll take out the nonsensical "I need I need to eat every 10 seconds" thing. Once I took that out, the game got so much better. And I did the other thing too. I made it so you couldn't leave anything outside of the template, right? So you have to match the template exactly. And then in addition to that, I made a random level generator so I generated these random templates for you to solve.

That was my second pass on the game, and I think I had something pretty fun. And then I got a call from my friend Andy Hull. Andy Hull is the is the programmer on the original Spelunky. We just caught up, and then he told me that he was feeling really, really burnt out. You know, from working on his last project. And I've always wanted to work with Andy. So I suggested, hey, would you still feel burnt out if you were working on a project with someone else? Because a lot of what he was doing on his previous game was a solo effort.

So here's what he said. He's like, "That sounds good, George, but I don't want to ruin our friendship." I think we'd both seen projects where people were friends going into it, and then due to the turmoil of the whole project, they don't talk anymore. So I can totally relate to that. So I suggested, "Andy, three months, let's work on this game for three months, three months is not enough time to ruin a friendship."

I picked maybe five of my Ludum Dare game jams that I felt could translate into a three-month game. And then I was like, Andy, I want you to enjoy working on this project, so I'll suggest these five, you play them all? This is your homework. Come back to me with the one that you think you're most inspired to work on. And he picked I Need a Lunch Break!

We already had our core gameplay. But at this time, the lead was still a human construction worker. And then, maybe a couple of weeks into working on this project. I was like: wait, I have this idea. I know this fact. It's the best fact in the animal kingdom. This animal from Australia, called a wombat? They have square poops. Their poops are shaped by little dice. Okay.

Garth, George Fan's PR person: You're right. It doesn't take three months.

George Fan: Yeah, what was Andy thinking at this time? I think I learned this fact maybe just a year before. I listened to this podcast all about it. And then, wait, can can we make a wombat our main character? And then because the poops are cubes, you could stack up poops and make your buildings that way. I had no idea if that would work. It was this outlandish thing to try. But we tried it. And it did work! Yeah, it was glorious. It totally fit. It gave the game a more unique spin. And then there's my goal, my goal with this game, which is to just make the world more aware of this awesome fact.

One of the things that's striking about your games is that they always have a theme like this, a theme that's arresting but also ties deeply into the game design?

George Fan: Yeah, I think themes are pretty important. If you can come up with something that resonates with people and it kind of stands out, I think that's the best. I think themes are pretty important when it comes to coming up with something that's doesn't just feel, you know, either too esoteric that people can't really latch onto, or maybe too generic that people have just seen a million times before.

I'm not really happy with the game until I feel like the theme is at least a little bit unique and maybe interesting, right? Octogeddon was another one I feel like I had a pretty unique theme. People could see a picture of like a giant octopus holding a submarine in a tentacle claw and you get what it is right away! But you're also kind of intrigued.

I think it comes from my personality, which is that it also has to apply to the gameplay too. I think I'm not really happy to work on something that's a rehash of something else. I always want to, on both sides of things - and probably more importantly for the gameplay - bring something new to the table. I'm more happy to work on something if it's something that maybe other people haven't encountered before. I think Hardhat Wombat has some has some cool elements to it that I don't feel like I've seen in other games, which I'm pretty happy with. And that also translates to themes because I definitely make a conscious effort to come up with themes that maybe people haven't seen before.

And sometimes they actually, you know, enhance the gameplay, like in the case of Plants vs Zombies. You know plants don't move, you know zombies move slow. And so that's why it's Plants vs Zombies. And it just so happens that those two forces have never fought each other before, so I had the uniqueness aspect there. But the the main reason why there were those two things was to support the gameplay. Okay, everything has to work. But yeah, at the same time, I want to do something a little bit fresh.