Ghost Trick and the joy of the ridiculous

This trick's a treat.

I recently wrote about coming to the 3DS ten years late, and how much I love it now, but the decision to pick it up in the first place was motivated by my desire to play a single game. I'm a known Ace Attorney fan since I played the trilogy collection in 2019. I wasted no time getting my hands on the other games, and it has become my favourite gaming series very quickly.

This prompted people to tell me about Ghost Trick, designed and written by Ace Attorney creator Shu Takumi. Ghost Trick, my friends would say, isn't just a good game or a great game, it's one of the best. Near flawless. By nature that's bound to make me suspicious, but when I finally got around to playing Ghost Trick on a borrowed 3DS, I was entranced.

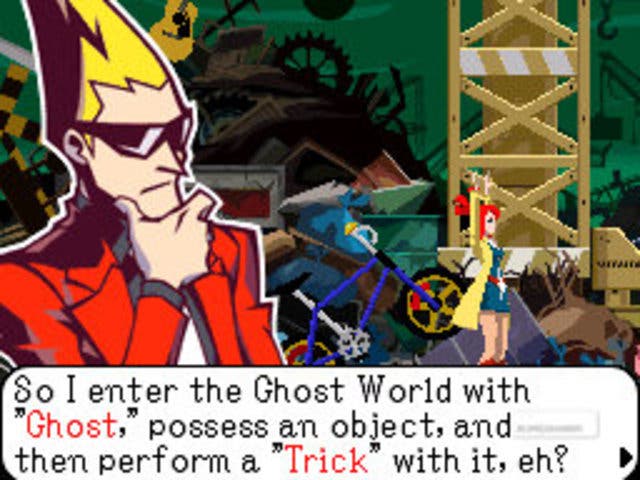

Ghost Trick: Phantom Detective tells the story of Sissel, who wakes up in a junkyard only to find he's dead, made evident by his body lying in the dirt before him, arse up (a scene which made for the game's fantastic cover art). Just seconds after this shocking discovery, he meets a desk lamp who tells him to save a young woman from certain death at the hands of an assassin, after she's already died. In order to do so you can possess different items: early on I'm possessing a bicycle to guide it along a powerline by its handles. It's too risky to say anything else about Ghost Trick without spoiling it for you, but if you're not intrigued at the prospect of, and I have to repeat myself, turning back time to undo a death as a bicycle, I don't know what to tell you. This isn't even the most ridiculous thing that happens in this game by far.

Ghost Trick got me thinking about the commonalities between Shu Takumi's games. After all, people were absolutely confident I, an Ace Attorney fan, would like Ghost Trick, and this idea had to go beyond the fact they were both made by the same person. Something coming from the same developer doesn't guarantee you'll like it. I think it's fair to call both games comedy games, in the way that they're intentionally funny.

But to me, comedy games aren't equal. Point and click comedy games, or any game inspired by LucasArts' legacy, create comedy by pointing their ridiculousness out to the player. Characters will acknowledge that their actions, other characters around them, even the whole setup, is inherently weird. Then there are games like Saints Row or Borderlands, where the character acknowledges comedy, but is also a part of it, resulting in a sort of supercharged mood. Most games are inherently ridiculous. That's in part where the discussion about games' narrative responsibilities comes from - if I acknowledge that nothing in a game is real and everything is comically overwrought, should the references to real life people and events really matter? (The answer is yes by the way, but that's a different article.) Games drop you in fantastical worlds and hope to immerse you by taking even the most unlikely circumstance very seriously.

Ghost Trick and Ace Attorney fall into a category of their own - they acknowledge the ridiculousness of their setup in the deadpan, LucasArts way, but they also take it very, very seriously. They're incredibly earnest and full of high-tension moments where you have to decide matters of life and death, and you defuse those situations by possessing a pair of headphones or calling a parrot to the stand.

This approach creates a fun paradox - by all accounts, you should be prepared for something ridiculous and unpredictable to happen, but you're still shocked. In Ghost Trick, Takumi doesn't solve mysteries by a deus ex machina, a sudden device hitherto unknown to you, he has placed in the scene, ready to reveal its meaning when the time comes. The whole story is a bunch of threads that will eventually connect, even by highly unbelievable means, and that made me feel that making up something so unlikely you could never guess it is just as much of a feat, if not more so, than coming up with a plausible explanation for a surprising revelation.

Even more so than Ace Attorney, Ghost Trick anchors certain mechanical constraints in its narrative, making it oddly believable - ghosts can traverse phone lines for example, but only if those phones have electricity, a constraint that naturally limits your area of play. A lot of things are too heavy for ghosts to move because...they're heavy and would already be difficult to move for people with corporeal bodies. Little rules like that make the experience of playing the game more interesting. This essentially comes down to finding a way around a room by way of possessing items, but it also makes sense. And that's even without thinking about the effort that must have gone into designing rooms and the items within them from a ghost's perspective - what items don't feel out of place in an interior, and if I were a ghost, constrained by the pop-culturally well-established fact that I can only move things a few inches, how would I use them? The thought processes behind Ghost Trick's design decisions are just so thorough.

Speaking of ridiculousness, one has to mention Ghost Trick's animations. Characters were made in 3D, then rendered into 2D sprites, and I haven't seen anything as smooth as this before. Shu Takumi has said the clearly cartoony way in which characters move is of course intentional, such as the little Michael Jackson dance Inspector Cabanela does when he enters a scene, or the way the justice minister anxiously tries to retrieve the telephone handset after he's been startled. According to Takumi, animating in this fashion can elevate games above real performances, since these are actions that feel more natural in an essentially made-up space.

Many games are going a different route - Watchdogs: legion gives you a hyper-realistic London for you to inhabit as a grandmothers who beat up people with their handbags, in Yakuza I beat up gangsters near the chicken skewer stand in Osaka I used to visit on weekends. These games embody the odd thrill of doing something forbidden in what seems like a real place. Yakuza is actually similar to Ghost Trick in how it employs comedy: Kiryu, more so than Yakuza: Like A Dragon's protagonist Ichiban, will acknowledge he's being asked to do odd things - then do them anyway, and with gusto.

There's a certain magic to that approach - Ghost Trick made me want to believe in ghosts, simply because it made believing look so easy. It didn't give me a hero who exists in a time period I know or in fact anything else that existed, but it made something unbelievable seem believable. Maybe I am surrounded by forces I can't see that are trying to help in small ways, just like the people I can see. It's a nice fantasy, born from me playing a game that doesn't shy away from simply asking "what if?"

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)