How Godus aims to reinvent the genre Molyneux created

A single shared world and another social experiment.

Peter Molyneux's got a problem, and that problem is Molyneux himself. Discussing his games becomes impossible without discussing the man himself, a public figure who is, depending on your own view, a dreamer, an innovator, a liar or just a plain fraud. It's something of a pity that Molyneux the man, fantastic spinner of soundbites that he is, has often eclipsed the games he's played a part in making. It's even more of a shame when the game that he's now working on looks to be the most interesting thing Molyneux's put his name to in years.

So I headed into a meeting with Molyneux in Cologne determined not to write about the man himself, and instead to put the focus on Godus, the culmination of the dream that sent him away from the corporate world of Microsoft and towards the more independently minded environment he finds himself in at 22 Cans. That change is explicit in our surroundings - it doesn't seem that long ago when Molyneux was taking the stage at Microsoft's conferences, but now he's taking meetings in his own hotel room, where he answers the door himself and demonstrates the game on a shabby set-up on a glass table where his tobacco vaporiser lies next to his MacBook Pro.

So yeah, it's hard to write about Godus without writing about Molyneux himself, but there's probably a good reason for that. Molyneux's put so much of himself into Godus, for better or worse, and it feels like his most personal endeavour in some time. "The whole story of the game started about three years ago when I started to see things like FarmVille and CityVille and all the others come out and being described as god games," he explains. "It made me sort of childishly angry. I'm not saying that was the only reason to leave Microsoft, but the opportunity to say those aren't god games, for me god games are something different, and wouldn't it be amazing to reinvent that whole genre?"

And that's what Godus is, essentially: an attempt not only to return to the genre that Molyneux helped invent, but also to remold and reinvent it. Does it work out that way? I'm not able to say, but a brief demo reveals that it is at least worth some attention, bubbling along enthusiastically with ambition and grand ideas.

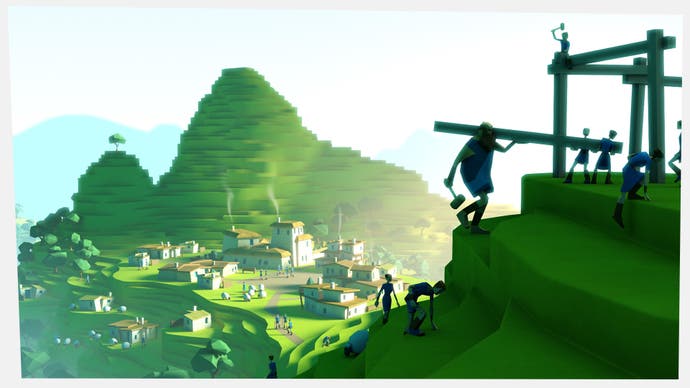

You start with just two characters clattering away at some stone in the middle of a vast landscape. From there, Godus provides little guidance or direction; those opening few minutes are spent in playful experimentation, clicking away at the environment and seeing how far your godly powers extend. At first, they're limited. You can click on the terrain to lightly terraform the world, and every action you take will have a consequence: bring down a tree and the ecology will change, while pulling back the coastline will impact the tide and flow of water. It's reminiscent of Eric Chahi's From Dust, a god game that, with its chaos and cruelty, dwelt more than most on what it would actually mean to be a deity. Godus takes that playful environmental manipulation and then runs with it, putting the concept into an open world with long-view objectives.

Those two characters can be placed in a hut where they'll proceed to breed, and from there it's possible to build a whole empire of followers who'll populate and help civilise the wilds. It's here where the grander vision of Godus begins to creep into view. "Many games, and I'm talking about things I've made before like Populous or Dungeon Keeper, you start to think why am I doing this?" asks Molyneux.

"Why am I continuing to play? And that's where you start to need a bigger motivation - if you like, the Curiosity motivation of what's inside the cube. And the long motivation here is what you're doing is slowly civilising your people. You'll take them from the primitive age through to the Bronze Age all the way up to the Space Age. And these little hamlets, these innocent little places are going to evolve themselves. They're going to be going around in cars with skyscrapers. The foundations of taking your people from an Adam and Eve to modern day is going to be an exciting one, and that journey's going to take many hours, certainly many days, many weeks and maybe many months."

But that's not the really interesting part. The shared experience of Curiosity, with people tapping away incessantly at the same cube, was more than a social experiment or, if you're more cynically minded, simple fraud. It was a testbed for the technology that distinguishes Godus, and it is, for better and worse, where you'll find the Molyneux touch: where ambition and design crash together, and where we won't know the real results until we've all had a chance to sit down and sample this new folly.

In Godus, you share the world with everyone else. The landscape's vast - in typical hyperbolic fashion, Molyneux says it's the size of Jupiter and will take thousands of years to scroll across, and he admits he felt a childish need to eclipse Minecraft's world which is currently as big as Neptune - and you'll have your own corner from which you're free to spread out.

If and when you stumble across another player you'll be able to either let them carry on in peace or challenge them to a multiplayer match, at which point you're summoned to an arena and Godus becomes a simple versus RTS. You can gamble what you take with you - if you're equipped with serious weaponry and come across a rival still stuck in the Stone Age then you may want to take only a handful of followers into battle - and here it's possible to win spoils to bring back into your world and help your quest for civilisation.

It's in the fuzziness of what will become of this world and how its inhabitants will interact that Godus' real fascination lies. Will the world become a warring hell coughing out pollution, or will it live in peace? Or will it simply peter out, another half-filled dream that ends in scrappy disappointment? Molyneux, of course, is optimistic.

"Well, that's what's so fascinating about technology today," he says. "What happens when you do connect everybody? When the two meet, that's when you decide whether you allow them to come on to your land or to make them an enemy. That's what's going to be fascinating. Are we all ultimately nice people? That's what my prediction is - there won't be any wars, we're just too nice. It's an illusion that we're nasty. Everyone will just come up to each other and give each other a big hug."