Gone Home console review

Unputdownable.

Gone Home has many ways of pulling on the player's heartstrings - especially if you're of a certain age, and given to welling up at the sight of button badges, or the lush click of cassette player buttons - but one of the game's most affecting tactics is simply that it lets you put objects back, exactly as you found them, with a context-sensitive input.

Houses in video games are seldom treated with this level of courtesy. They exist to be barged into and ransacked, their incidental furnishings trampled or smashed in the quest for loot. But in Gone Home every object is a belonging, and the game cultivates enough sympathy for its cast that meddling with their effects comes to feel indecent. Even the Greenbriar family's garbage has an aura of sanctity. I carefully replaced a scrunched-up manuscript page on the floor next to a bin after reading it, for example, wary of disturbing the scene in however trivial a fashion.

This is a troubled kind of reverence, however, because Gone Home is also a charming if familiar tale about how our belongings may come to define and limit us, a lesson about the periodic necessity of letting everything go - and, without wanting to sound too bookish, a clever excavation of the operations of sexuality and gender within a white, middle class American family in the 1990s.

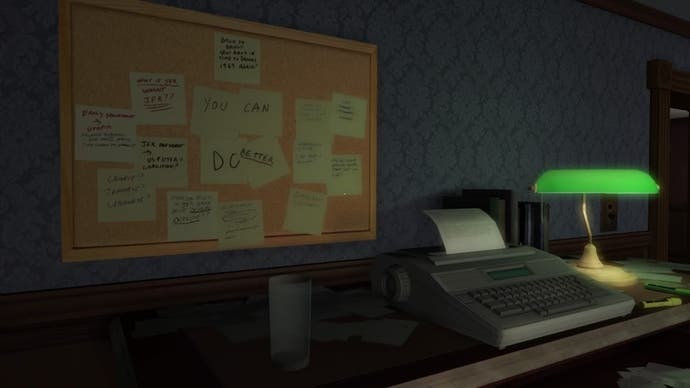

You play the eldest Greenbriar daughter, Kaitlin, who returns from a gap year in Europe one dark and stormy night to find the family's new house deserted and dotted with cryptic Post-It notes from her sister Samantha. Kaitlin must then scour the place for hints about events during her absence, poking through bookshelves, closets and under sofa cushions for pregnant snippets such as biro sketches or concert tickets, while polishing off a couple of find-the-key puzzles. An almost silent presence throughout, she's a smart choice of protagonist - sufficiently independent that, like the player, she can take more of a detached interest in the private lives of her relatives, where Sam is still struggling to escape their coils.

On picking up certain objects you're treated to a voiced extract from Sam's journal - the most prosaic of the game's narrative techniques, and the area in which the story sometimes veers from sweet to sickly, thanks in large part to a cloying guitar accompaniment. These are sparing interruptions, however: for most of the game you'll be sifting the detritus in silence, filling in the blanks at your own pace with only Kaitlin's winningly personalised context-sensitive command text (e.g. "Gosh, Dad") for company. You can also now disable Sam's voiceovers if you'd rather play blind.

Drawing on its collective experience with the BioShock series, The Fullbright Company has amassed a landscape of suggestive trinkets that don't merely echo or elaborate upon one another, their shared themes sinking in as you trot from room to room, but which are palpably the property of intelligent personalities who are well aware, amongst other things, that their possessions tell a story. As the centre of the mystery, Sam's debris is the most abundant and mischievous: her bedroom, which plays host to a combination lock puzzle, is a delightfully cheeky jumble of red herrings. This isn't just obfuscation for the sake of challenge. It evokes how children cobble together their own colourful languages of metaphors and motifs as camouflage against the probing of parents and siblings.

The mother and father are more reserved, their emotional lives ossified within letters to publishers, schedule planners and legal correspondence. In the father's case, this bureaucratic numbness adds pathos to the portrait of a novelist whose insecurities and inhibitions infest his work - among my favourite touches in the game is the doleful discovery of a porn mag underneath a pile of dusty press copies. In the mother's case, though, I'm minded to echo Oli's criticism in Eurogamer's original review that Gone Home is too slight to do its characters justice - there are twists in her tale, but she has much less of a textual presence. Mind you, the point is perhaps that the mother is too much the homemaker, too preoccupied with everybody else's needs to express herself as freely as her daughter in what she leaves behind. It is, as with much else, up to you make sense of her silence.

Oli's original review also called attention to the discrepancy between Gone Home's horror movie leanings - the Greenbriar residence once belonged to a mentally infirm uncle, and there's the odd explicit nod to the occult - and the quirky family drama at its core. I have mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, peals of thunder, flickering bulbs and the suggestion of a disembodied voice are well-worn cliches, and they do create expectations that the plot doesn't fulfil (though you can look forward to a few surprises). But I like how the game keeps you guessing about the kind of story it is, and the fact that Sam is herself a bit of a ghost-hunter becomes a source of humour - her scribbled accounts of spooky events around the house are another way of getting under her sister's skin.

The game's evocations of the fantastical also speak to how the characters role-play, whether it be the father trying his arm at a sort of everyman James Bond in his novels or Sam's raucous short stories, which you'll see evolve from childhood doodles to energetically pasted-together gig posters and fancy dress costumes. This is an elusiveness I wish more character-driven games were capable of. Video game NPCs are commonly open books, the better to serve as resources for the player, but if there's one thing human beings are famous for it's the capacity to pretend, rejecting the identities we're assigned by each other and by society. Gone Home is littered with artefacts, such as school exercises, family portraits or smelly old boardgames, that are insidious little instruments of social control; Sam's defiance or playful reworking of them is what makes her such an appealing personality.

Mind you, Sam's efforts to break free of her circumstances are perhaps too straightforwardly successful to be credible. If Gone Home's coming-of-age yarn has a critical flaw, it's that it's excessively optimistic to the point of feeling sanitised - a few steps beyond what players who have personal experience of similar events may be willing to let go. You can, of course, make the case that there's nothing wrong with a beautiful fable, but Gone Home is too accomplished a work of realism and naturalism for that justification to be entirely convincing. Its grounded yet sunny outlook is admirable, but doesn't quite add up.

Nonetheless, the game outshines these misgivings in the wit and texture of its environment, an environment that comes to seem much larger than its navigable expanse, thanks to the little histories of sadness and hope that cling to each and every prop. To boil it down, Gone Home stands apart from other narrative games in three respects. It understands that what we own both is and isn't who we are. It appreciates that characters are often most vivid, most solid in their absence. And it knows that the one thing you can't put back is time.