Good games done slow

Easy does it.

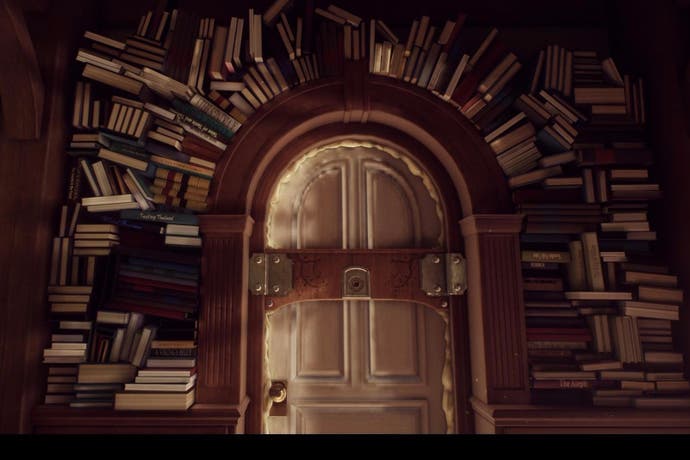

There are a lot of books in the Finch mansion. Books on the shelves. Books on the floors. Books on chairs. Books over doors. If you find your way into the kitchen - if you find it by fighting your way past stacks of books, naturally - you'll find that there are books all over the kitchen, too. I don't remember checking the sink, but there are books everywhere else, piled on work tops and spread over counters.

On my second visit to the Finch mansion I came with a camera. I was playing on Steam rather than my first runthrough on PS4, and I was screenshotting anything that leapt out at me - and in a game like What Remains of Edith Finch, almost everything leaps out. One thing I quickly noticed on this trip was that the Finches have a lot of copies of Gravity's Rainbow. No harm there. I have one or two in my own house, which is nowhere near as rambling or unpractical as the Finch place, where a book can be laid down only to go permanently missing, so I don't doubt that they might have picked up quite a few - particularly with all that coming and going.

But jeepers, they have a lot of copies of Gravity's Rainbow. And a lot of copies of some other books too: a lot of Infinite Jest, a lot of The King in Yellow. This was a pleasant revelation. I didn't feel I'd spoiled anything. I didn't feel, in some strange way, that I was diminishing the achievement of What Remains of Edith Finch. I just felt like I'd discovered one of the many tricks no doubt employed when filling out this miraculous game's miraculous world. Someone put all those books on all those shelves. Sometimes, they had to copy a few books to pad things out. They probably went back, over the course of development, to make sure the arrangement was aesthetically satisfying, and to make sure that you never got a cluster of Pynchon or a motherlode of DFW. I also just like to imagine the moment of creation: a 3D artist, sat before the monitor, making books, making books.

I did not spot any of this on my first playthrough, in part because my wife was driving and I was sat too far back from the screen, but mainly because we were entirely hooked on the game at this point, hooked on the sad mystery of the Finches, and we were taking the whole thing at speed. My second playthrough, though, has been a very different affair. The game holds up, but is transformed. It is transformed by the fact that I am looking to the edges rather than being drawn to the center of the narrative, certainly, but it is also transformed because I have slowed down.

Man, it is brilliant to slow down in a game. And only a certain kind of game can take it. Some games are built for speed, for velocity and sparks and the rattle of concrete seams beneath your tyres. This is fine and I love it, but I also love the game that allows you to dawdle, that not only wants you to look back over your shoulder in a way that you're not expected to, but which has put something there for you to see when you do.

It is a certain kind of relationship you strike up with a designer when you take things slow. It is almost like you are being drawn into their confidence, like you are being offered cheat codes. "Here is how we filled all those book cases," says the team behind Edith Finch when you slow down. "Here's how I made this short tower look like a tall tower," says Brendon Chung on the director's commentary for Thirty Flights of Loving, a hectic headlong pelt of a game if ever there was - but also one that, amazingly, you can pause in, mid-stream, and see all the beautiful detailing, from the double-pace planes flocking by the airport windows, to that destination, WEST EGG, popping up on the departures board. (He made the short tower look tall, BTW, by placing regular lights on the walls, and then sneakily narrowing the gaps between these lights the further up he went. Your misperceptions did the rest)

It strikes me that these two examples are from the genre we often call walking simulators. And why shouldn't they be rich with detail, why shouldn't they be built for an ambulatory pace, for a player who has brought a camera along? The thing of it is, though, if you're truly committed to slowing down, a surprising number of games can be walking simulators. There are so many things to spot and enjoy in Burnout Paradise, for example, a racing game that also lets you coast to a full-stop, and will do cool things to you if you do, in fact. There are so many things to enjoy in Grow Up, once the campaign is done and you've got all the crystals. This one isn't even about going slowly, since those crystals give you infinite jetpack fuel. Instead, it's about going aimlessly, about zoning out and letting that jetpack fuel rocket you, in beautiful white bursts, out across a landscape in which each place you visit offers a wonderful alluring hint of another place, and so you move on and on, joining the dots and accruing sweet details - details that feel like they have been left for you and you alone. There is a special halo around a game that allows you to coast through the shimmering blue facade of a waterfall and touch down on the cool earth of the cave that lies behind it.

Maybe we are more into slowing down at the moment. A colleague of mine a few months back nudged me and showed me the video he had been watching for some time - a freighter of some kind, hauling shipping crates between glowing points in the South China Sea. On my way to work today I finished S-Town, the latest podcast sensation. It tells the roundabout story of a man living in a small town in Alabama. It is a slow burn, lots of digressions, lots of details that have made themselves visible only through the time and the deliberation taken in the telling of the story.

It's not a huge leap from S-Town to Edith Finch, and I strongly recommend both. They will not take you long to work through - unless, of course, you choose to take it slow.