Has the Art World Finally Fallen for Video Games?

A new Smithsonian exhibit puts games in a major gallery for the first time. Eurogamer finds out whether they fit.

There's a whiff of triumph hanging in the air above the Smithsonian American Art Museum's central courtyard. It's the opening day of the venerable Washington DC institution's Art of Video Games exhibition and the everyday throng of tourists and art enthusiasts have temporarily been displaced by an incongruous hoard of excited gamers here to see their favourite titles share wall space with David Hockney and John Singer Sargent.

On the gallery's third floor, cosplayers snake past sculptures and installations by some of the great artistic minds of the 20th century on their way into the exhibit, while in the basement theatre below an array of big-name speakers including Hideo Kojima, Ken Levine and Pong creator Nolan Bushnell line up to deliver their commentaries to rapt audiences. Heck, even hot sauce magnate/Donkey Kong fiend Billy Mitchell is doing the rounds.

On paper it seems like a significant event; a sign that America's starchy cultural elite has finally accepted the humble video game as a valid and interesting form of artistic expression, rather than just frivolous brain-rot for bored teens and lonely man-children. Could it be that a line has finally been drawn under that tiresome old 'games are art' row?

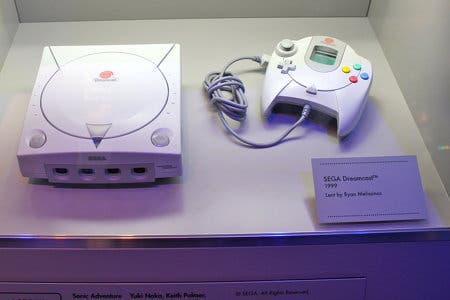

The exhibition, which runs for six months before touring a number of other US cities, is curated by one Chris Melissinos - a veteran games industry evangelist and former Sun Microsystems gaming chief. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he's keen to hold up the show as proof that a new age is indeed dawning for the medium.

"This is a validation that the Smithsonian believes video games are worthy of examination as an art form in our world today," he tells Eurogamer.

"I think we are crossing a threshold here. I hope the exhibition helps creators in how they view the games they create, and the struggles they have as a growing industry and as a growing form of media. I think it could be a turning point."

As evidence of its potential impact, he goes on to recount the almost-Damascene conversion of the museum's aged docents when he was first invited to pitch the idea a couple of years ago.

"I had several people come up to me - all women in their mid 50s to mid-to-late 60s - and say, 'I have never considered video games in the manner in which you have presented them, and I will never look at them in the same way again. We didn't realise these things existed, we didn't know what they were trying to convey. We didn't realise the breadth of this'."

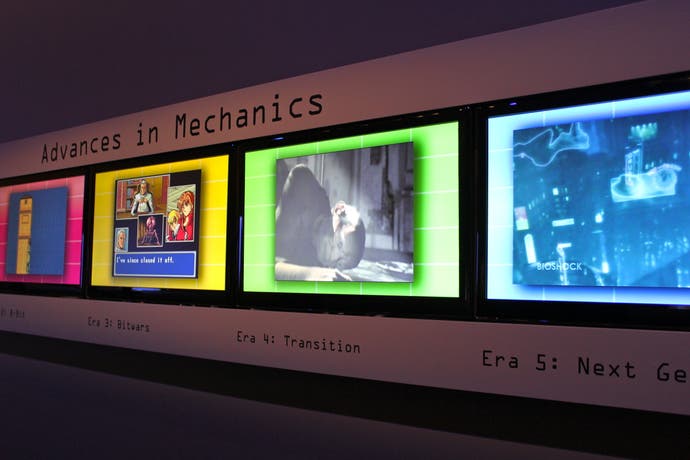

Alas, closer inspection of the exhibition itself highlights just why many critics have been so slow to acknowledge that games might boast hidden depths beneath the blinking pixels. While the show's chronological rundown of gaming's brief history certainly makes for a fun stroll down memory lane, it offers precious little impetus for contemplative chin-stroking.

The artistry of, say, BioShock or Dark Souls or Shadow of the Colossus unfurls gradually as you play through the game - not in a light-bulb moment while staring at a screenshot. As such, the walls of the Smithsonian are an unsatisfactory, unhelpful conduit to convey their complexities. If anything, the snatches of concept art and gameplay footage on display only serve to show off what an uncomfortable pairing games and art galleries really make.

Ken Levine - speaking to Eurogamer prior to his opening day panel with Melissinos, BioWare Mythic creative director Paul Barnett, former Nintendo US man Mark DeLoura and thatgamecompany co-founder Kellee Santiago - agrees that they make strange bedfellows.

"It didn't have a huge impact on me," he admitted, when asked how he felt seeing Bioshock showcased in his nation's cultural nerve-centre.

"It was sort of an artefact-y, low-res video of it running. And my experience is a huge screen right in front of me; me interacting with it in a huge room where it's the main draw. It was a little strange to have such a... it's a bit cursory, you know?

"It didn't say anything that hadn't already been said. But it said it to a different audience, which is why it's meaningful."

And that's the key. While the show might not add much to the discussion, it does offer the world of video games some proper, grown-up exposure. And let's be honest, as proven by the ill-informed debate over SOPA and the relentless stream of silly tabloid shock stories, that's something the industry still badly needs.

"Games are really under-served in terms of how they are recognised by the mainstream press," argues Levine.

"People worry about games being over-exposed. Games are not over-exposed. How many times did you see a Clash of the Titans image before that movie came out? You just can't avoid it. Whether it's a TV ad or The Daily Show or whatever, you're seeing that stuff over and over again.

"With games, unless you spend tonnes and tonnes of money on advertising, most people are just not going to encounter them because regular people aren't reading Kotaku or Eurogamer or whatever. So I think it's really good the more exposure games get."

But as proof that games are art? That's a debate Levine couldn't care less about.

"It's a meaningless discussion because games are what they are. People can't even agree on what the definition of art is. So to have a debate on whether something is something that isn't even defined is attenuated as a conversation.

"It's a bit 'looking over your shoulder'. Are we ok? Are we art? I don't care. The term 'art' constituting some kind of quality validation is not something I think is meaningful.

"There are all these media forms of expression, and I think it's a great form of expression as it's the only one that really has a dialogue with the audience."

Levine's point about the mainstream press is an important one. It's slowly improving, but game coverage in UK papers (not to mention here in the US) remains hopelessly threadbare. If this exhibition can help move the medium out of the tech pages and into the culture supplement - where any right-thinking gamer knows it belongs - it will have done its job.

"You know, dance gets in that [culture] column," points out Levine.

"I've nothing against dance but how relevant is dance in terms of a cultural element? Or even classical music, compared to games right now? In terms of people who are affected by it, people who follow it, the amount of money spent on it, by every measurable standard gaming is huge, right?"

In the same way that mainstream discussion of superhero movies took decades to reach the point where we can now enjoy intelligent think-pieces about, say, the morality of The Dark Knight, Levine argues that it's just "a matter of time" before gaming eventually breaks through too.

Back down in the gallery courtyard, a stiff-looking DC bureaucrat giddily babbles down his phone to his partner about how he's just seen some original World of Warcraft character sketches, while nearby a youngster patiently explains to his parents what Metal Gear Solid is. Later, in the metro station a few blocks away, a group of thirty-somethings can be seen talking freely about their experiences with Mass Effect 3.

There's no logical reason why this sort of public chit-chat about gaming should be jarring - after all, you overhear people raking over the previous evening's TV all the time - but it is.

Kellee Santiago, fresh from the release of thatgamecompany's thoughtful multiplayer experiment Journey, argues that, ideally, the Smithsonian's stamp of approval should encourage more of this sort of uninhibited public discourse.

"For so long video games have been marginalised as kids' stuff. That's how it was marketed, that's how it was talked about. And if it wasn't kids, it was that group of white dudes in a basement," she replies, when asked why it's taking so long for the establishment to take video games seriously.

"Simultaneously, the industry found a lot of success with those audiences. So there wasn't a lot of financial motivation to move off that message.

"I hope that this is an important event in that it's a milestone in elevating the discussion we have around games. And not even elevating it in terms of the kind of words we use, but just saying, 'This is something we should be talking about. Games are part of our culture, they're here to stay.'

"Developing the vocabulary around which we discuss games is what allows us to hold developers more accountable for the kind of experiences they create and allow them to continue to evolve the industry. In the long run that would make this a huge milestone," she continues.

"It seems like for every other entertainment medium in our culture - whether it be music or books or film - you and I could engage in a dialogue about any one of those subjects. We have a fundamental understanding about how to talk about them and what goes into them. I think it's important that games are taken to that level as well - that they're inclusive, not exclusive."

While the Smithsonian's exhibition might not offer died-in-the-wool curmudgeons convincing proof that video games should henceforth be filed under fine art, it hopefully demonstrates two things: that those on the inside need to be a little less insecure about their treasured pastime, and that those on the outside need to sit up and take notice. Once we get past those hurdles, great things will surely follow.