Hohokum review

But is it game?

Hohokum's scenes are unfamiliar - beguilingly so. In one, a tall violinist plays a melancholic tune while he stands under the throbbing light of a lamppost. His squat buddy sings full-throated by his side while, overhead, the buckshot stars wink approvingly. In another, an Indian elephant with a deep underbite plods through the jungle while a caged albino orangutan dangles from his tail, praying to be freed. Elsewhere, a businessman sits in the belly of a vast and complicated Heath Robinson-esque machine, waiting for bees to drop honey into its pipes which will travel through the tubing and, finally, be deposited in his coffee cup as a steaming drink. These are fever-dream vistas - the kind of places you wonder whether you've remembered wrongly, whether you were ever really there at all.

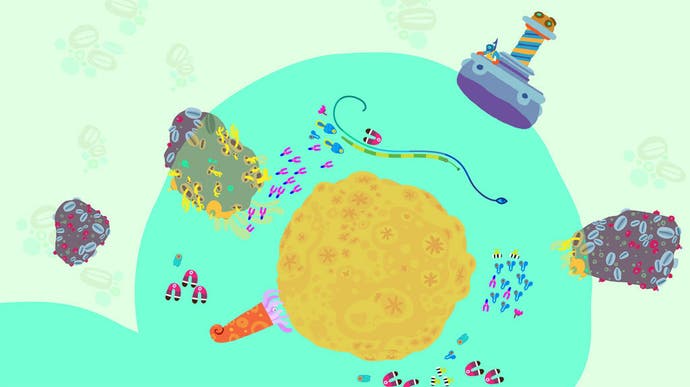

You play Hohokum as a lithe snake known as Long Mover - or, more accurately, as the unblinking eye that sits at the head of the snake, its lingering tail sweeping behind. Hohokum's range of interactions is slim: go fast, go slow, steer. As you move through these weird scenes, you create trailing shapes with your tail while, every now and again, you can change things in the environment by butting into them with your head.

Meanwhile, the game's palette of colours, shades, shapes and swirls is vast - but meticulously so. These painterly hinterlands are filled with Pantone fauna. Every psychedelic colour complements the next. It's striking, beautiful. Simply flying through these scenes, loop-de-looping overhead, swooping through the trees and rushes, is enough. No matter that the usual video game clutter is absent from the screen: the score ticker, the map, the inventory, the clutch of lives. This is a video game doing something that only a video game can do as it places you inside the landscape of its creators' imagination.

For those for whom these quiet miracles aren't enough, Hohokum has some clearer goals. Your snake chums have been scattered and lost throughout Hohokum's opaque world. One is hidden in each of the game's large, multi-screen scenes and you must solve the scene's puzzle in order to rescue them. There is no text in the game (its few characters speak in an indecipherable Ur language) so the shape and contours of each puzzle must be felt out, made explicit through prodding and trial. They are ingenious.

You rescue the albino orangutan by ferrying his buddies on your back to a stack of brightly coloured seeds which they can then hurl at the elephant (while the wizard standing on its head fires Japanese shoot-'em-up style bullets at you from the tip of his staff). Another scene references Nokia's formative Snake game, sending you through a series of test chambers through which you must find your way. Each time you solve a world's puzzle, another of your snake friends is rescued and sent back to the mysterious hub scene at the start of the game.

The second goal is less obvious. In each scene there are a number of eyes hidden in the scenery. Fly over these and they blink awake. Find all 146 eyes hidden throughout the game (no simple task) and you have the opportunity to unlock another ending. This secondary goal primarily exists to encourage exploration, as you move through the black-hole entrances and exists of each scene, looking for watching eyes in the ferns, hanging from the bases of platforms and nestled among the barnacles undersea.

For some, this will not be enough. Those players who need their games to have a to-do list for a spine will baulk at Hohokum's lack of clarity and urgency. But to damn Hohokum as an art game, an interactive installation, is to miss its clarity of purpose, its tightly wound design, its glorious idiosyncrasy.

As with many singular works, Hohokum's strengths are, when viewed from a certain angle, also its problems. The murkiness of its structure (scenes link to scenes via portholes which you fly through, a rabbit warren of entrances and exits that even the most attentive player will struggle to memorise) means that you'll often become lost. The game's almost unwavering decision to eschew words and numbers means that it's difficult to keep track of how many snakes you've rescued (though, curiously, the designers are happy to report the number of eyes you've found). The opaque puzzles offer a jolt of satisfaction when you finally feel your way through the conundrum, but if you become lost there's no support offered: you must fly about in search of a solution or retreat to the internet for guidance. There are times when you grow aimless, a short hop away from boredom.

No matter: this is striking video game art and design, a game that builds on no particular tradition, instead forging its own path, borrowing style and ideas from a range of media. There's a bit of drug-tinged 1970s children's animation here, a little Katamari Damacy oddness there, a layer of 20th-century Disney invention everywhere else (the crows that flap like umbrellas opening and closing could have been lifted straight out of a Dumbo dream sequence).

The effect of the game's soundtrack shouldn't be underestimated, either. It swings from hyper-cool French electro to post-apocalyptic M83, altering the tone of a scene with unusual swiftness. One scene is a giant water park, filled with tiny people in rubber rings, splashing happily under the sun. Fly through a mountain pass and the scene switches to some unspecified future date, the park now derelict, the sun diminished, the music a sorrowful lament to a bygone time.

The combined effect of this maze of vivid, diverse, shifting scenes is memorable. You are Alice, touring wonderland, seeing how deep the rabbit hole goes. In Hohokum, it goes an awfully long way: it's deep, it's wide and, perhaps most importantly, it's temporally long. This is a game that sticks with you long after you switch it off.