How a lifelong diet of games influenced The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle

"I went to video games and did not realise I was doing it!"

"I forget everything between footsteps.

"'Anna!' I finish shouting, snapping my mouth shut in surprise.

"My mind has gone blank. I don't know who Anna is or why I'm calling her name. I don't even know how I got here. I'm standing in a forest, shielding my eyes from the spitting rain. My heart's thumping, I reek of sweat and my legs are shaking. I must have been running but I can't remember why.

"'How did-' I'm cut short by the sight of my own hands. They're bony, ugly. A stranger's hands. I don't recognise them at all."

It could be a video game. It could be so many video games - you in an alien body, the moment the action begins. It could be you in the back of the plane in BioShock, you shaken awake in Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, you on a slab in DOOM. But it's not.

It's a book, and from the moment you open it, you're off at a pace which never lets up, hurtling around an Agatha Christie world filled with characters and rules you desperately want to understand. Who are you? Why are you there? You barely have time to think. Time is always against you, and there's a hunter on your tail. You're never quite sure where the blade will come from but you know it will come.

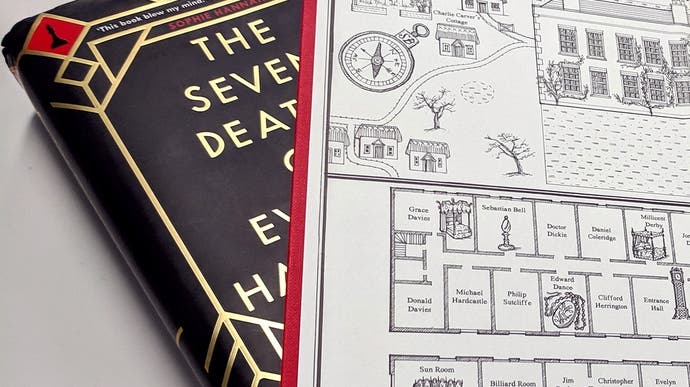

But to describe The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle as a mere murder mystery would be a disservice, for there is something much more inventive going on. An old formula is spun on its head by an inspired, game-changing twist. It just won author Stuart Turton a Costa Book Award for First Novel. I've never read anything like it.

I have, however, played games like it. What's remarkable is Stuart Turton never made the connection. "It got pointed out to me immediately after people started reading it," he tells me now, sat in a room recording a podcast interview [which I am working on making available again now]. "I'd not intended it as a video game, I never thought about video games when I was writing it."

It's remarkable because Turton knows games. I can see a Nintendo Switch peeking out of his bag. He lives and breathes them, grew up on them. He even says he reads Eurogamer, the charmer.

"I've been playing games since the Dragon 64, this old shitty, pre-Spectrum computer." Oh and that's another thing about Turton: he swears - he's delightfully Mancunian off the page. "I was playing Chuckie Egg and Treasure Island, which I could never get past the first level of because it was shit-hard and I don't think they ever finished it."

He's 38 years old, Turton, and he's from a working class background up north (you can feel his disdain for the upper-class in his book). In the flesh he looks a bit like an older Harry Potter, he'll hate me for saying - a messy crop of curly greying hair on top of a bespectacled, inquisitive face. He's loud and open, eloquent and informed. He's good company.

After the Dragon 64, he moved onto LucasArts point-and-clicks (he had to imagine the voices because he didn't have a sound card), and after the point-and-clicks, first-person shooters - like every other teenage kid in the Quake era. These days it's XCOM and Crusader Kings, with a splodge of Pillars of Eternity and Assassin's Creed Odyssey thrown in.

So how central are games to his life? "Very. I play something every single day," he says. "Sometimes I'm knee-deep in writing, and it's genuinely taxing, it's genuinely hard, and all I want to do is get into a DOOM and let my hands do the work - I don't want my brain doing too much. Whereas I have other days where I'm massively frustrated by the writing and I need something super-absorbing to pull me away from the problems I've been working on, because that distance will help me solve them. I carve out an hour for myself a night, even when I'm writing. It's crucial for me."

It means even though Turton didn't intend gameyness in his Agatha Christie novel, it creeped in anyway. He subconsciously pulled from the things which shaped him. "I went to video games and did not realise I was doing it!"

The less you know about The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, the better. Stop reading if you'd rather preserve every surprise, much as it pains me to say. But also be reassured there are no major spoilers ahead and very few I'd consider spoilers at all (there are, however, huge - albeit well telegraphed - spoilers in the accompanying podcast).

This one is written on the book: in The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, you relive the same day through the eyes of a different person over and over until the murder is solved. But it's not until you begin to learn every minute of the day, the way Phil Connors does in Groundhog Day, or until you understand each character the way Dr. Sam Beckett does in Quantum Leap, the tables begin to turn. Which sounds pretty cool, doesn't it?

Turton tried to write it when he was 21. "It was garbage," he says. "It was just horrifically bad - rip the hard-drive out of your computer and smash it bad (and then burn the computer and salt the ground). It was awful.

"It was a load of Agatha Christie tropes just mashed together onto the page. It didn't do anything new, it didn't add anything to the canon. I wanted to have an idea that would raise it up, that would allow me to put it on a bookshelf and not be ashamed it was being compared to Agatha Christie, and I thought I'd have that idea in a week, I honestly did."

It took 12 years.

Turton was in Dubai when the idea of body-swapping and time-looping smacked him. He was working as a travel journalist, living the life with the love of his life, on the 30th-floor of a beautiful apartment block overlooking the marina. He was sent on holiday two weeks of every month. He had everything he wanted - but he didn't have a book.

He hadn't been able to shake the idea ever since it reared its head. "It changed my entire life," he says. He became a journalist because of it. "I knew I wanted to write this novel - I'd always wanted to write this novel - but I knew I wasn't very good," he says. "I didn't know how to write, I didn't know how to structure, I didn't know a thing about pace. Becoming a journalist was my way of training myself."

But once the idea hit, Turton knew his life would have to change. The book was too important to him. He had to write it, and he knew he couldn't in Dubai. He had to be in the place where the country mansions were for research. He needed to feel the rain on his face as his characters would. He had to be in Agatha Christie land, had to be England - and he needed his girlfriend to come with him.

"We gambled a fuck-ton on this book working and me pulling it off," he says, which had the sobering side-effect of his knowing "I could never quit" - how could he look his wife in the eye if he did? "She agreed to come along with me," he adds. "We left all that behind and we ended up in a tiny little flat in central London above a children's nursery for three years. Every day I would hear the children playing and screaming while trying to write a book."

The immediate reason The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle feels video gamey is because it's told in first-person present tense - very much, "I am doing this," over and over. The idea was to give you and the main character the clues at the same time, theoretically enabling you to solve the mystery with or before him - although I feel there's a change about halfway through when the protagonist goes a step ahead. Nevertheless, it's nothing less than urgent.

There's also a familiar feeling of rising power. A classic power fantasy, in other words. Think about it in games, says Turton: "You start with no power, your weapons are stripped away from you, and you gradually build up your arsenal, Metroid-style, until you get to the end, by which point you're far too powerful for the game you're playing and it's almost a formality you're going to finish and complete it."

Now apply it to The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle: "The character doesn't have any information at the beginning of the book. The world is completely unknown to him, he doesn't know why he's there, he doesn't know why this has happened to him, he doesn't know who killed Evelyn. As he goes through, though, he begins to piece it all together and begins to use the time-loop to his advantage - he works out how to do that. He begins to use it to get ahead of the people who are after him and do clever things. It's very BioShock at the end, going to confront the final boss."

You could, I suppose, even consider the character's bodies as different lives. You could look at their strengths and weaknesses as character classes - some fast and fighty, others slow and thinky. And when time loops around and things begin again, it's like restarting a level in Hitman, the guards setting off on predetermined patrol routes.

Then, there's the violence, which in The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle is especially horrible and disturbing - much more so than the gratuitous gore of DOOM or Assassin's Creed. It's this way for a reason, Turton explains.

"Violence is something we all treat as fun," he says. "I used to be involved in martial arts and I've been hit in the face a lot, and it really hurts! But you see it in movies and you see it in video games - people are getting punched and shot - and they shake it off and carry on about their day. As I got older, that began to bug me, our general societal attitudes towards sex and violence. It's an obvious thing to say," he almost apologises, "but it's all skewed and wrong and weird.

"When I set out to write the book, I wanted to make sure the violence was horrific. Not just because it builds threat and tension, but because it should be terrifying. If you're fighting somebody in a ring, there are rules to keep you safe. But mostly, if you're out on the street and you get into a street fight, there's going to be more of them than there are of you, and it's going to be a horrible, depressing, despairing thing that's going to leave you damaged for weeks or possibly worse, for the rest of your life. I wanted that sense of carnage and rebuke to the way we treat violence in our society.

"It's horrible to write."

But perhaps the strongest contributor to a video game feel was having a world with set rules - only, these weren't ironed out until surprisingly late in the day. It wasn't until an American publisher was interested, rules were pushed to the forefront. Call it cultural taste.

"The US edit was far more interested in the rules of the house," Turton says. "They were very specific about upfront wanting to know what these rules were. I think a lot of that is where the video game feel comes into it, by establishing the rules nice and early. In the UK edit, it felt a bit more loose around the edges, had a bit more of a dream quality to it. There were definitely rules but they weren't being explained as early.

"That was brilliant - that was a brilliant call in the end."

It wasn't easy, putting it all together. A body-hopping, time-looping murder mystery presumably never will be! "If this would have been my second book, I'd probably never have started it," he laughs now. "I had the advantage of ignorance."

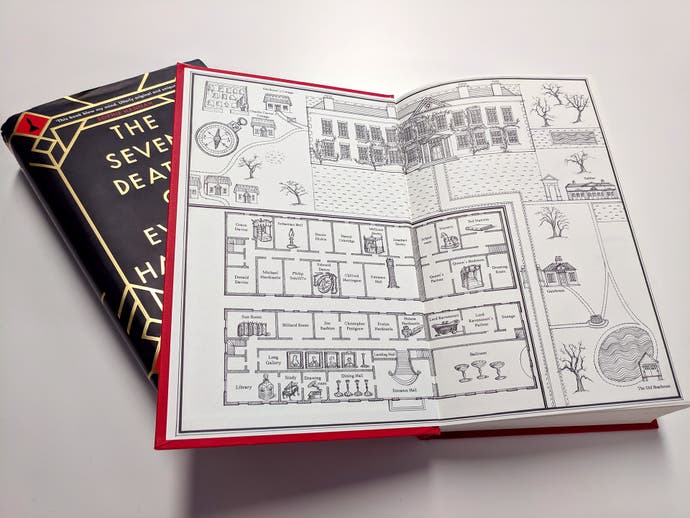

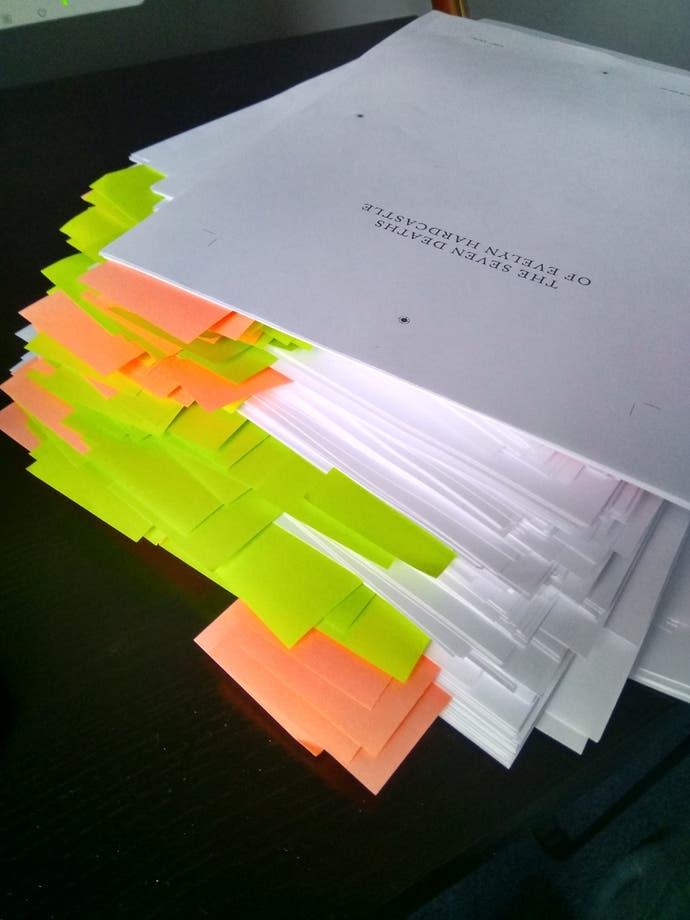

He managed it by planning out every two minutes of every character's day on one huge spreadsheet, which took him three months. Then he boiled it down into two-hour chunks, plotted it on a giant paper map of the house and grounds, and stuck it on his bedroom wall. On the other wall, meanwhile, he stuck Post-it notes, reminding him of themes, of thoughts, or ideas. I bet his wife was thrilled.

He would wake up each day and pick a part of the book, from his spreadsheet, he wanted to write. "If I had a day where I felt like writing a big fight scene, I'd write a big fight scene," he says. "If I wanted to write a philosophical bit, I would find a philosophical bit on my plan and write that bit. I ticked it all off the plan as I went along, and there was a second tick for when I thought I'd edited it nicely and was happy with the writing in there.

"I wanted for myself," he adds, "to make sure there was one beautiful thing on every page, so even if it was a page of exposition, I always wanted there to be one nice line, one nice reflection. It wasn't necessary by any measure, but it was necessary for me, as the creator of the book, to have that in there - that's what gave me pleasure.

"At the end of the day, two-and-a-half-years on this thing, with six months of editing, I needed to try and entertain myself every, single, day. I needed to make sure I was enjoying what I was doing - and that is what I enjoyed doing."

Two times he came close to the edge. The first was when he thought he had an agent, a process he calls "soul-destroying", and it turned out he hadn't, which left him "floundering" and doubting himself. And the other was when he spent seven months writing 40,000 words he'd ultimately chuck in the bin. He'd gone off-plan, you see, followed a whim, and plotted himself into a corner.

To appreciate the effect it had on him, you have to consider the strained circumstances he was living in. Not only had he promised his wife the book would take a year, "We had piss-all money because I was working three days a week," he says. "I was making just enough money every week to cover the bills and to have a pint with mates, but that was pretty much it. There were no holidays any more. All this stuff that was the base of our relationship when we met was suddenly cast away."

In no way could he afford the seven months he threw away. "It was devastating," he says. And to make matters worse it was in the cold, grey lead up to Christmas. "I had to stop for a month." He went full-time freelance for a change of scenery and some income to pay for "a couple of nice things". But after the bell struck midnight on New Year's Eve it was back to it.

"The book had to work."

In the end it was a combination of stubbornness and pride - and no doubt a truckload of support - which got him through. Three years later the book was done - about the same time a video game takes, coincidentally.

The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle was released almost a year ago to the day: 8th February 2018, and has justifiably been a big success. I don't ask him about numbers because I think it's crass, but suffice to say he's been able to move from flat above the nursery and buy a home. Mind you, he's still writing in the corner of bedroom - in that way nothing has changed. He was turfed out of the spare room he briefly enjoyed by the arrival of his baby girl. Hence the Nintendo Switch - snatched gameplay sessions are all he has time for.

Stuart Turton's new book is coming March 2020, and he's off in Australia writing it now (he was in Brighton in December to record this interview-slash-podcast). "I've got a two-book deal with Bloomsbury, my publisher, and they would like another book with a body at the centre," he says. "But, god bless them, that's all they've asked for.

"So, it's another mystery but it's exactly the opposite in almost every circumstance. Still fun, still complex, still a lot going on, a lot of sub-plots and a lot of character work, but I've left the time-travel off, I've left the sci-fi/fantasy off. It's far more historical - and it's far more epic."

He's not interested in writing a sequel or a prequel to The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle. "I don't particularly want to write one," he says. But it's an area which may be explored for television nonetheless. A production company is interested, he tells me. It's why Turton can't answer some of my bigger questions about the book's ending. "If it did go onto the screen, they may be interested in doing more of that sort of stuff," he explains, "and I would have consultation with that. But they want this story, they want this book."

A more appropriate question for us to end on, however, has to be what a video game of The Seven Death of Evelyn Hardcastle would look like. "Sexy Brutale probably!" he answers right away, and laughs. "I tell you what, when that game was announced, I shit myself. I absolutely shat myself. Bits of that, bits of Maniac Mansion...

"What I'm loving about Return to the Obra Dinn at the moment is it makes you feel like a detective. It makes you actually do detective work. It's not just throwing icons at you to chase after. You constantly scribble things into a book, you've got to deduce things. It would have to do something like that. You would have to be the character and you would have to be clever. I'd want it to make you feel clever all the way through.

"And unlike most video games, where the power fantasy is everything and the challenge lies down beneath it, I would love it to feel almost insurmountable - you would have to chip away at it constantly to get through it.

"And then maybe have an Alien: Isolation-style constant threat roving through the game so it could just come out at any time and end that character," he adds, " and then you're in the next one. Ah! That would be awesome."

Much like, I must add, his book.