How AI is changing video game development forever

Are we headed towards a new "AI winter"?

AI NPCs. AI scriptwriting. AI voice acting. AI artwork. AI creation tools. Yes, AI is everywhere in game development. In the past couple of years it's arisen as something of a dirty word, an inevitable future. But the future is already here.

A report by Unity earlier this year claimed 62 percent of studios use AI at some point during game development, with animation as the top use case. This report was based on responses from developers using Unity tools, which may skew responses to the more indie and mobile end of the market - but it seems a familiar story across the industry. Last year, Microsoft announced a partnership with Inworld to develop AI tools for use by its big-budget Xbox studios, and in a GDC survey from January, around a third of industry workers reported using AI tools already.

Some uses of AI have been widely criticised: take, as just one example, the cast of Baldur's Gate 3 revealing the darker side of the game's success fuelled by AI voice cloning. US actors union SAG-AFTRA has had to scramble to work on an AI voice agreement to protect workers, while a new AI licence from Speechless aims to provide an ethical approach to AI in voice acting. But does AI spell doom and gloom for the games industry generally, or are there some positive use cases? What does an AI future look like? And why, now, is the progress of AI for positive means also under threat?

To find out more, I spoke with AI expert Dr. Tommy Thompson at the London Developer Conference. Thompson is an academic and consultant for the games industry in artificial intelligence technologies, who also runs a YouTube channel on the topic. And to start with, before discussing the future, Thompson gives his view on what exactly we mean by AI, and why some forms of it have garnered such a negative reputation.

How to define AI

To use an academic definition, AI is "any piece of software that has two key qualities", Thompson begins. "It's autonomous, which means it will behave entirely of its own remit - you give it input, it will act upon it in its own way - and it is also rational in the context of the problem it's trying to solve." For a video game example, take pathfinding - where an NPC character autonomously figures out how to follow behind you, navigating the environment using a method rational in the context of the designer's intent.

More recently, Thompson acknowledges, "AI" has alternatively been used as shorthand for generative AI, which is more a part of machine learning - where an AI makes correlations between an input and an output. So-called deep learning, meanwhile, refers to the additional complexity gained via artificial neural networks. Generative AI is a subset of deep learning that adds contextual relevance.

An example of this is a language model like ChatGPT. "It's able to figure out the statistical relevance of certain words in conjunction with one another," Thompson says. "And it understands what this word means as a term within the context of a sentence or a paragraph or a larger body of text.

"Subsequently, when it generates text, it's able to generate something that sounds reasonable and first passing because it's figured out by reading more text than any humans ever read, how to generate an output that sounds statistically likely."

Generative AI can be used as a shortcut, then, but the results are often lacklustre. This is why, Thompson says, a lot of language models are "kind of milquetoast, the handwriting is very generic and often lacks flavour", because "it's averaged out the experience of all human writers on Earth."

The biggest issue with generative AI, and why Thompson believes there's so much "scepticism and general distrust" of it, is that systems are trained at large scale on masses of data without enough transparency on where that data has come from. Some of it may have been stolen and scraped, and should not legally be used. "I think it's justifiable that people are not happy about it," Thompson says, "because whether it's text or - I think more critically - image generation, people's work has been used without their consent and it is generating stuff that is reflective or evocative of their artistic merit and integrity."

Copyright infringement has therefore become a huge problem, as these systems are so data hungry and difficult to control. "I feel like the bigger companies that have largely committed all sorts of legally infringing..." he trails off. "They've stolen data and have now set a message and have set the conversation around generative AI in a way that's going to be very difficult for people doing it ethically." As a result, there's been public pushback against the use of AI in games - or, as Thompson puts it: "the game playing populace as a whole has indirectly spoken up as an advocate for the human creator".

How AI is already used in games

So, are there any positive examples of AI used in game development? Thompson has plenty.

In-line with Unity's report, animation is a key area - particularly animation blending. Essentially, developers will create separate animations for character movement, but when does a walk turn into a run and then turn into a sprint? Blending these animations together smoothly is a painstaking process, but AI can be used to do this cleanly through motion matching. Games like The Last of Us Part 2 and Hitman Absolution use this process, among others. "Animation blending is great because it shows a quality of the product that to do that with human labour would be significantly harder," Thompson says, also highlighting AI's ability to catch human errors.

Other examples are seen in cheat detection and dealing with toxicity. Microsoft recently revealed how it uses AI to identify harmful words, images and voice chat reports, to ensure game communities are kept safe. Ricochet, the anti-cheat system used by Activision in Call of Duty, uses machine learning to combat cheaters as part of a multi-faceted approach. Counter-Strike 2 has a similar system, employing AI to scan gameplay for irregular activity that may suggest aim-assists, vision assistance, or griefing. Using these systems allows developers to spot issues at scale.

Crucially, humans are still required as part of these processes. "This is a critical part for how generative AI can actually succeed in the industry, in that humans are always the final authority on any action that is taken," Thompson says. "But the system is helping to do that: we often refer to that in game design as mixed initiative design."

A further example of this is SpeedTree, a generative tool for building trees in games. Trees aren't necessarily the sexiest of things to design, but human users still have the final say over the design and placement of them so can focus on creating the bigger picture rather than the minutiae. The practical use for this is obvious, but that's not the case for every new AI tool being developed.

"Games are getting bigger, games are getting more complex, we need better tools to support us," says Thompson. "And I think, funnily enough, we're hearing from both the players but also from a lot of the developers, the tools that we're being told are going to be the new wave of AI for game development aren't what we need a lot of the time."

"Games are getting bigger, games are getting more complex, we need better tools to support us."

Despite rapid advancements in AI over the last few years, Thompson believes we're about to enter a new and ominous-sounding "AI winter". This refers to a downturn in the technology's development following a period of significant investment, as apathy kicks in due to lack of results and investment dries up.

In the 1970s and 1980s, investment in computing intelligence typically came from the military, while the current boom in deep learning and generative AI has been largely supported by corporations. Thompson suggests that, as these corporations now fail to see much of a return on their investment, cashflow could diminish and an "AI winter" could set in.

"How much money do we need to throw behind this before we start actually getting returns?" Thompson asks. "And that's a justifiable question. It seems like for a lot of these companies it's not quite there yet.

"All the really loud, noisy [AI companies] are going to maybe either abate or die off entirely," Thompson predicts. "And then you're going to start seeing a new wave of stuff coming in that is a bit more practical, a bit more user-friendly, eco-friendly... and more respectful of artists as well who have been dragged into this without their permission."

An AI winter means less investment, then, but greater focus on specific, innovative needs, as opposed to the current boom of flashy technology that initially impresses but doesn't stand up to scrutiny. Crucially, the groundwork is already being laid for better regulation - be it EU laws or Steam approvals.

In-house vs third-party AI tools

Many studios are now creating their own in-house AI tools rather than third-party tools. This may be to solve a specific problem, but it's also about protecting their work and owning their process.

For instance, a studio may decide to use an image generator to experiment with some new concept art, so will use their existing - human-made - art as data. But how can they trust that a third-party tool won't take that data to train their own system? What if that data is then used to build, as Thompson puts it, "some half-baked clone on a mobile store somewhere"? "If you went and put your images into one of these third-party tools, you're feeding the very beasts these people are exploiting," he says. "If we're feeding our assets to these companies, we're just making our own life more difficult."

The law is a key contributing factor, with tools needing to comply with EU copyright laws and regulations. Transparency of datasets and processes is needed, which third-party tools cannot always guarantee.

Another question: how can companies guarantee these third-party tools will still exist in a couple of years time? The bulk of money invested in companies developing AI tools pays for infrastructure, and Stability AI - which runs a myriad of image, video, audio, 3D model and text generation tools - spent $99m on Amazon Web Services in one year, and at one point defaulted on its bills. And that's before staff costs too. Earlier this year, Stability laid off 10 percent of its staff following the exit of its CEO.

"A lot of these companies are getting a lot of money to be first to market to show they can do something, but very few of them have actually got a business plan that shows they know how to survive two years, five years, 10 years, while also making the money they need in order to keep these models up," says Thompson. And as AI models get bigger, they require more data, require more money to keep up and running, and more investment is required. And when that falls through, it leads to an AI winter.

All of these costs are leading to a division between AAA studios and indie developers - who can't afford to create their own in-house models either. But for indies, perhaps the biggest hurdle is Valve's approvals process for Steam. This identifies two types of generative AI: pre-generated and live-generated. For the former, developers must prove where the data has come from and that it's copyright compliant, but depending on the tools used this isn't always possible.

"All the big AAAs are building their own tools because they don't trust the third parties," Thompson says. "A lot of indies are rushing out to try out these third-party tools and then are being burned when they get to the submission process." And if indie developers struggle to get on Steam, then PlayStation, Xbox and Nintendo are even more restrictive.

What's the future for AI in games?

Will AI take over from humans entirely? Tech solutions firm Keywords recently attempted to make a 2D video game relying solely on generative AI tools, though found it was "unable to replace talent". Said Keywords CEO Betrand Bodson: "One of the key learnings was that whilst GenAI may simplify or accelerate certain processes, the best results and quality needed can only be achieved by experts in their field utilising GenAI as a new, powerful tool in their creative process."

Thompson agrees the results of experiments like this have been poor. And that's the critical question: if we do move towards this future, how good will the results ever be? "Great games are fundamentally the product of a human," says Thompson, detailing how happy accidents can occur during development, but areas like UX and UI absolutely require human input.

"I feel like we could get AI to a point where it just builds the entire thing, but as someone who is very engrossed in this space, I'm like: do I want to play it?" Thompson says. "I think that's an equally valid question. It's like if people are getting ChatGPT to write an article, then why should I bother reading it? You couldn't even bother to take five minutes to write it. What artistic value is there in something that didn't have a human as part of this creative process?"

"What artistic value is there in something that didn't have a human as part of this creative process?"

As an example, Thompson highlights The Rogue Prince of Persia, a fun take on Ubisoft's long-running series from the Dead Cells team. Would an AI really capture what makes these different franchises great in a mash-up of the two? Would it understand the tactile controls, the unique visual aesthetic, the kinetic and frantic combat? "I don't think [AI] would inherently understand the quality of those," says Thompson. "I think it'd be much more surface level and lack that depth and nuance a human creator brings to it."

Weighing up the potential benefits of using AI in game development along with key issues, Thompson says he's "cautiously optimistic", but likens AI research to Jurassic Park's fictional recreation of dinosaurs. "You did it because you could," says Thompson, "you didn't stop to think whether you should."

Generally speaking, despite more AI tools being developed, they often have limited use cases without solving fundamental issues. ChatGPT is, in Thompson's words, "the world's most intelligent autocomplete", or a "digital parrot". It might be impressive work but the crux of generative AI - as already discussed - is it doesn't actually understand or think for itself. "What so many of these companies do is they reach out and they go and make the thing because it looks shiny, it looks exciting, you can get lots of funding, but you didn't solve the crux of the issue," Thompson says. That's why each new tool is often met with scepticism, he believes, despite perhaps being initially impressive.

"There's a lot of pessimism, but also increasing apathy towards generative AI," says Thompson. "We're in such a hype cycle right now."

"What so many of these companies do is they reach out and they go and make the thing because it looks shiny, it looks exciting, you can get lots of funding, but you didn't solve the crux of the issue."

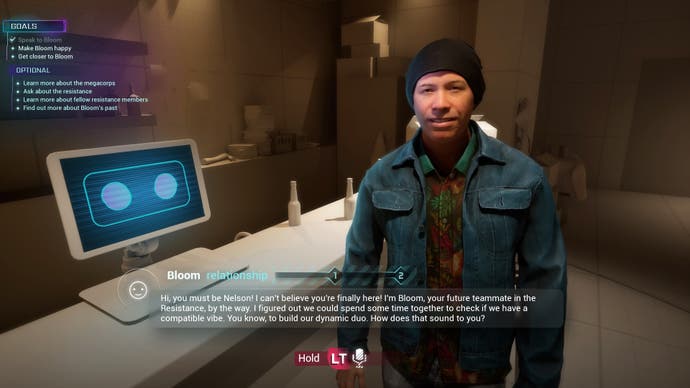

It certainly feels that way. Just recently, PlayStation Studios' head of product Asad Qizilbash was the latest in a string of execs praising the benefits of AI. "Advancements in AI will create more personalised experiences and meaningful stories for consumers," Qizilbash said. "For instance, non-player characters in games could interact with players based on their actions, making it feel more personal. This is important for the younger Gen Z and Gen Alpha audiences, who are the first generations that grew up digitally and are looking for personalisation across everything, as well as looking for experiences to have more meaning."

It sounds flashy enough, but can companies really deliver on these buzzwords and statements? Or, to paraphrase Game of Thrones, is winter coming? "The proof," says Thompson, "will be in the pudding."