How Dishonored: Death of the Outsider makes rats of us all

Eat the rich.

Editor's note: Once a month we invite the wonderful Gareth Damian Martin, editor of Heterotopias, to show us what proper writing about games looks like before we shoo him away for making the rest of us look bad. You can read Gareth's pieces on Dark Souls and Resident Evil - and you really should! - before settling into this month's piece about Dishonored and its rats.

It was a rat that told me what was in the basement of the Taxidermist. It and it's beady-eyed allies were milling around the backstreet outside, the smell of blood presumably having brought them to this particular doorstep. In a surprisingly soft voice, the rodent whispered poetry in my ear, a song of gnawing teeth and matted fur. The rats, it seemed, were the ones who knew this city best of all, and as I listened they told me of its secrets. I won't go into specifics-I wouldn't want to spoil the surprise of that basement or the other hidden places I've visited-but as you might imagine, what I found down there wasn't something particularly pleasant.

Dishonored: Death of the Outsider, a standalone addition to Dishonored 2 and the conclusion to the series' loose trilogy, is filled with these unpleasant discoveries. Seen through the deeply pessimistic eyes of assassin Billie Lurk, it often feels as if under every flagstone of Karnaca is some concealed atrocity. Gone is the southern light that gave Dishonored 2's depiction of the coastal city an edge of glimmering luxury, replaced instead by a flat grey glow that emanates from a veiled, milky sun, like the cataract of some dead god. Perhaps it's the removal of the so-called "chaos system" from the game-a kind of moral compass that the series carried, rewarding less murderous players with better outcomes-or the mutterings of the sardonic Billie-"the rich pay to poison themselves with this shit" she observes while skulking around an exclusive spa. "Wish they'd just finish the job"-but either way Death of the Outsider feels like it embraces corruption and inhumanity in a way the series has never quite managed before.

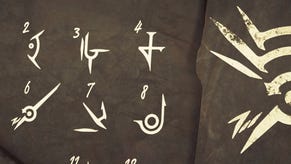

Billie Lurk is at the centre of this. Like her mentor Daud, who in the first games' add-ons-The Knife of Dunwall and The Brigmore Witches-managed a significantly more gruff and gritty persona than the game's original protagonist, the silent and elegant royal protector Corvo, she is disconnected totally from the powerful aristocracy that rule Dishonored's isles. Corvo may have been pulled up from the gutter to the heights of the royal palace, but Billie never left - well, apart from when she had to slit the throats of some upper-class fool in his personal quarters. Living through her, it's hard not to discover a vindictive streak for those that prey on the weak and poor. And there are plenty of those to prey on: Death of the Outsider has you work your way up the ranks of the "eyeless", a cult funded by bored, wealthy, self-proclaimed geniuses who wish to taste the other side of existence-Dishonored's mystical "void." To do so they commit unspeakably dark acts. In one powerful vignette, you witness them literally draining the blood of a kidnapped man, torturing him to the edge of death, while they pontificate about the aesthetic experience of mortality. Even their drink of choice, "Plagued Spirit", is fashioned from cruelty, containing a pickled rat that sits like a biological specimen in its piss-coloured bottle.

And there, right on cure, are the rats again, those spirit animals of the series. Plague bringers, flesh-eaters, but also allies, assistants and useful tools, they have infested Dishonored since day one. Death of the Outsider, both through Billie's talent for hearing their piping voices, and her matching nihilism, reminds us of their importance once more, taking our focus away from the gleam of industrial machinery and the glimmer of luxury, into the gutter and its denizens. And so, when I came to try to understand the spaces and architecture of the series, it was the rats that seemed like they might provide the perfect bodies through which to do so.

Rats, after all, are more than just pests. When it comes to urban architecture they are perhaps its true residents, spreading to every imaginable space. There's an often mentioned idiom in London that you are never more than six feet from a rat, and having lived here for more than a decade I am often convinced it is true. In his wonderful book Rats, which explores the history and habitat of New York's infamously vast rat population, Robert Sullivan explains that "to know the rat is to know its habitat, and to know the habitat of the rat is to know the city." Sullivan is not just being poetic here, rats have a powerful relationship to the architecture we have built. They touch its every corner, explore even its most forgotten volumes, find its concealed entrances and dim passageways. Sullivan explains his realization that "history is everything when it comes to looking at rats-though it is not the history that you generally read; it is the unwritten history." To explain, he recounts a story told to him by an exterminator who was tasked with clearing a colony of rodents that was essentially self-replicating: no matter how many were killed the infestation remained. "The exterminator searched and searched." Sullivan writes "At last, he found an old tunnel covered by floorboards, a passageway that headed toward the East River. The tunnel was full of rats. Later, he discovered that the building had housed a speakeasy during Prohibition."

It's a powerful idea-that rats live not just between the walls of our everyday spaces, but in our history too. Like the secret tunnels that led to the New York speakeasy Sullivan describes, rats share our most hidden spaces, even after we have forgotten them ourselves. Larry Adams, a rodent control expert who Sullivan speaks to in his book, seems almost paranoid when he points out the other shadow cities our everyday cities hide. "A lot of people don't realize that there's just layers of settlers here, that things just get bricked off, covered up and all. They're not accessible to people, but they are to rats. And they have rats down there that have maybe never seen the surface. If they did, then they'd run people out." I'll forgive you a shudder there, at the idea of millions of subterranean rats living beneath our feet, suddenly rising to the surface. But the point is not the horror, but the history, the sense of a thousand interlocking spaces that cut through our cities in ways we can't imagine and will never know. The strata of society.

Returning to Dishonored Death of The Outsider with this in mind, we begin to see how the rat is more than just a symbol of disease and destitution for the series. The beauty of Dishonored's cities, from the London and Edinburgh inspired Dunwall, to Karnaca's hybrid of Barcelona and Havana, is their sense of layered space. The developers, particularly the exceptional artists and series art director Sébastien Mitton, have become masters of a particularly architectural sense of history.

Just take the first level of Death of the Outsider, the Albarca baths. Perhaps the smallest level in a Dishonored game, it demonstrates perfectly how refined Arkane's approach has become. Once a public baths, but now repurposed as a boxing club, it is designed to reflect both its current use and its history equally, with a symmetrical layout cut through by new routes and additions. There's little narrative history about the baths in the game, but the sense of the space's changing identity over time is palpable from just exploration. The faded beauty of its soft blue tiles, the decaying fixtures, and rusting boilers, all point to a once functional space, repurposed. But what makes this particularly effective is the way that Dishonored allows us to get a total vision of this space. We crawl through access panels, slip through holes in shattered tiles, and edge along dusty, forgotten walkways. Like Sullivan's image of New York's rats, who are able to pass through history as a series of volumes and layers, we are able to move through the space like no other. This design extends to the whole of Karnaca, a city whose alternating layers the game encourages us to cut through as if we were spelunkers descending into a cave network. In short, Dishonored's distinct urban exploration, with its layered histories and countless concealed passages makes rats of us all.

And yet there is something else to the game's obsession with rodents that goes beyond the stratification of cities. That something feels particular to Death of the Outsider, and its commitment to dive into the deepest caverns of human corruption. In it we live the fantasy of the rat, not just as the ultimate urban explorer, threading through spaces in configurations unknown even to the humans that built the city, but as the avenging angel of the poor and the downtrodden. As I picked my way, rat-like, through the game's levels, rising up through the basements to slice the throats of the nastiest images of privilege, power and exploitation I have seen in a game, I was reminded of the romantic poet Robert Southey and his poem God's Judgment on a Wicked Bishop. Based on the story of Hatto II, a particularly cruel Archbishop of Mainz, it retells the story of how in a time of famine he burnt the poor on mass rather than give up the grain in his granaries. In the poem Hatto, after gathering the poor in a barn and setting it alight declares "I'faith 'tis an excellent bonfire!" before adding:

"And the country is greatly obliged to me,

For ridding it in these times forlorn

Of Rats that only consume the corn."

But the next day, the archbishop finds his granaries empty, and an army of rats on the march. Retreating to his fortified tower, supposedly the Mäuseturm on the Rhine, he locks himself away, sure that he is safe. But as we know from Sullivan, rats can cut through architecture with ease:

"And in at the windows and in at the door,

And through the walls helter-skelter they pour,

And down from the ceiling and up through the floor,

From the right and the left, from behind and before,

From within and without, from above and below,

And all at once to the Bishop they go.

They have whetted their teeth against the stones,

And now they pick the Bishop's bones:

They gnaw'd the flesh from every limb,

For they were sent to do judgment on him!"

So ends Southey's poem, and the profoundly evil Hatto II. But real life does not run so cleanly. Take Peterloo massacre, which happened in 1815, during Southey's own lifetime. In it, cavalry charged into protesters demanding parliamentary reform, who were massed in St. Peter's field in Manchester, killing many and injuring hundreds. No plague of rats came for the men that ordered that violent hateful act, and Southey himself, who ironically became a staunch conservative in later life, tried to gather support for branding the dead and injured criminals and to support the government's attack. I mention this because Death of The Outsider feels like a fantasy akin to Southey's early poem, and a rebuke a society so forgetful of events like Peterloo. Like Southey's poem, the game lays out the relationship of rats to architecture as analogous to their relationship to the structures of power and corruption that make up the human world. They alone can cut through the barriers to enact bloody justice. They are the vengeful spirit of corrupt times, and in the end, Dishonored Death of the Outsider carries the belief that power, no matter the walls it surrounds itself with, is never immune to a set of sharp, hungry teeth and a pair of beady eyes.