How FIFA Ultimate Team got its hooks into the spirit of football

Buy-out claws.

A thousand things go into making a person and a lot of them aren't football.

One part of being a young father is remembering with still soft-shelled vulnerability all the anxieties and defeats that shaped the adult you've not quite become. This is OK because you have a few months at least during which it's impractical for children to leave the house alone, time which can be given over to indoctrination and the provision of a map clearly marking all the pitfalls and snares in which some part of you is still trapped.

But then at some point they won't be with you every day, and you won't be able to human-shield them from life and all its happenings. They will enter a room full of other children and begin a life apart from you, and at this point you're powerless except in the preparation already undertaken. And this is why we played FIFA.

As a sporty kid who read David Gemmell books down the school corridor and was never ritually beaten, I've always understood that boys who are good at football are typically immune from bullying. I chose FIFA for me and my son, Jay, during the time of Pro Evo's unquestionable superiority because its licenses seemed a shortcut between living room learning and the real football I wanted him to fall in love with. I wanted him to know heroes that he could watch on Match of the Day and pretend to be in the garden. And I wanted their names to be spelled properly.

This is what the meaning and value of officialness boils down to, really, a collapse in the gap between make-believe and real. And it's an edge FIFA still holds, regardless of how good the game itself is in any given year: the dreams it sells are stored on a lower shelf, and are easier for little arms to stretch for.

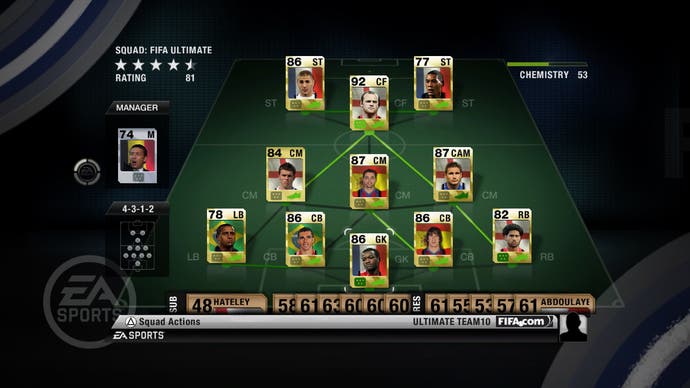

These days that officialness has become something else. Described a certain way, FIFA Ultimate Team sounds like an almost nostalgic addition to EA's football series: a card collecting game with packs to open and fantasy squads to build, alive with the plimsoll-smell of playground trading and swapsie decks. But it's also an elegantly contrived system of temptation and scarcity, where the thrill of discovering what stars might tumble from your torn packs has as much to do with economics as it does adulation.

Jay describes opening packs in FIFA Ultimate Team as "gambling" (he's no longer the heartbreakingly hopeful child tottering onto the mercy of other people - his Ultimate Team is called Bnta, abbreviated to LOL in the live score display). His Ultimate Teaming follows a pattern of boom and bust, of constructing a squad - paying attention to the game's foibles of chemistry and quality - and then selling up to fund another binge of purchases. He understands the flow of inflation and deflation over the season - high early prices flattening as the league dwindles - and he spends as much time trading as he does playing football.

And so what? There have long been sport management games, given juice by the raw wrangle of the transfer market. But Ultimate Team's design funnels desire and value in a particular way. At the centre is that officialness - the swabbed reality of football that FIFA is selling, player by player. We want to build a team of the best footballers, and there are two ways to get them: through packs, or through the market.

The market is FIFA's auction house, where managers like Jay list for sale players found in packs. The currency here is FIFA Coins, which can only be earned in-game by playing matches, or through the sale of your own players. The number of Coins won per match varies depending on things like result, score and stats, but is typically between 500 and 1000. It's hard to find a good player - the kind of player worthy of a bedroom poster or a few extra quid for lettering on the back of a shirt - for less than 100,000 Coins. A full squad might need a million.

The other option is packs. Packs are bought with Coins too, but also with FIFA Points, the game's second currency which players can purchase through microtransactions. This gives EA tight control of Ultimate Team's economy: Coins are distributed at levels set by the publisher, and while players are invited to invest real money in their virtual squad should earning Coins prove too slow, this money must first be run through the pack-filter of randomisation, the parameters of which are also set by the publisher. It's a way of preventing us from simply buying the transfer targets we want. It's a way to keep us gambling.

The economy accentuates the thrill of opening packs - landing a star player doesn't just make your team better, it might also lead to more money to buy more packs to feel more thrills of finding star players - and in so doing it shifts the basis of a player's value from footballer to tradable commodity. The most excited I've ever seen Jay playing FIFA was when he recently packed a Team Of The Year version of David Luiz. He threw his headset onto the sofa and shouted "No!" in a dark, convincing way that made me worried he was having a panic attack. He jumped up and down and rang his friends and posted a picture of Luiz on Instagram. All of this, and he never had any intention of playing with him whatsoever.

As a manager Jay is twitchy and impatient, a dealer as much as a football man. And that's because Ultimate Team reflects the transactional frenzy of football itself. Money is now the defining force in football, and transfers are a fundamental way this money expresses itself - the exercise of power and exchange. Transfer windows and deadline days have become an insatiable stimulus, and we hunger for more change and more hope. Ultimate Team is an unending transfer window, adrenaline-drenched and hollow.

The hook of romance and hero worship I originally had in mind when I chose FIFA was based on an understanding that, when I was 10, Gary Lineker wasn't just priceless, he was an object that existed outside of economics and untouched by systems of relative value. During the 1990 World Cup I completed the Esso garage coin collection, the jewel of which was a shiny disc etched with Lineker's face and signature. The possession of this item simply felt good, and made sense of the amount of time I, a wobbly right-footer, spent recreating that control off the right knee in a panicked German defence and a left foot equaliser, and why - to this day - Nessun Dorma plays in my head whenever I take penalties.

I ask Jay who his favourite player in the world is.

"Gareth Bale."

We saw Bale play during Tottenham's Champions League run, his form that season one of those sawn-off miracles that makes clinging to football by the corporate bunting and navigating the North Circular at rush hour seem worthwhile despite everything.

"What would you do if you got him?"

"I do have him."

It transpires that 750k of the David Luiz transfer Coins saw Bale installed as the centrepiece of a new team that Jay is still perfecting. Maybe romance isn't totally dead.

"Would you ever sell him?"

"It depends..."

"Right."

"...on whether his price is going up or down."