I Am Dead review - a beautiful meditation on the things that we leave behind

Decease and assist.

Down at the campsite and under the blue wash of moonlight, Edie the owner is dreaming about Greg. Greg is dead. He owned the campsite before Edie, and the handover was awkward - nothing dramatic, just a difference of philosophy. Greg seemed austere and obsessed with rules - tent dimensions, guy rope types, no ball games. But there was another side to him and Edie saw it too late. Now as she dreams, she considers the person she may have misjudged. Is this how relationships go, between the living and the dead?

We can peer into Edie's head here, just as we have peered down into her home on the campsite, the roof stripping back as we move closer. Just as we peered down into the campsite itself, roving between its distinct spaces, plucking them out, rotating them, inspecting them. Hidden object games are often 2D affairs - here's a beautiful picture, and can you find the haunted earrings, the crank for the Victrola, the keys to that funny Citroen with the odd suspension? They are often an elaboration of the books we had as children: spot this, circle that, where's Wally?

I Am Dead is not like that. It's more like the toys we had as children. Its spaces are painted in Mr Men colours but they are thick and chunky and intricate and ready to be turned in the hands and investigated from all angles. And they're magical. You can select a house and slide your eyes through the roof, through the beams, through the floors and right down into the basement, everything from a sofa to a hat-stand strobing past as you go. You can pick up a jar of pencils and rush through the lacquer, the wood, the little pipes of graphite in the middle. I Am Dead was inspired by a video of a banana in an MRI, and there is something of the MRI's eye, of its unflinching nature to it - something that makes me strangely squeamish, just for a second, as a pass through an orange tree reveals the little baby segments of orange inside, as a slide through an octopus leads me to the private cavities in the unspeakable density of the octopus' head. Mostly, though, it's wonder and joy. What would a child put inside an MRI? What does the inside of a toy car look like? Is there a ship inside this bottle? Wonder! Joy!

And there are other valuable emotions as you move outwards. I Am Dead casts you as Morris, a man who spent his life on the volcanic island of Shelmerston, running the museum and knocking about with his dog Sparky. Then he died, and the dog died. And now they're both back, both ghosts, because Shelmerston's ancient guardian is ready to move on, which means that the volcano will erupt unless another guardian - another dead island resident who wants the big job - is located.

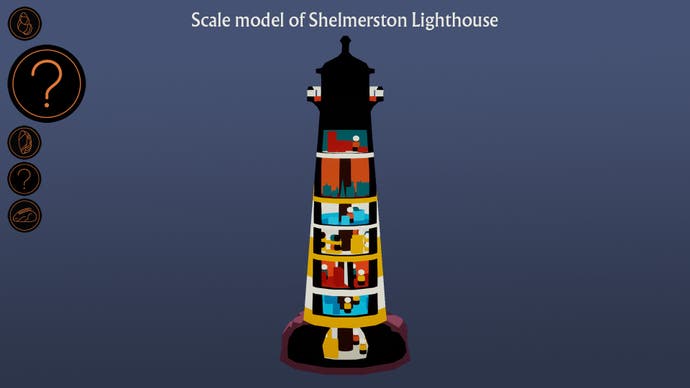

There are a number of candidates for Morris and Sparky to talk to, but first they have to manifest as ghosts. This means tracking down people who remember these dead people, and then locating a number of cherished objects that link the memories and the person together. Separate stages! You move to a new setting - a lighthouse, say, or a strip of the seafront, or an ornamental garden - and you rove around looking for people with thought bubbles coming from their heads. These are the people who knew the deceased in question. Then you move into their heads and unjumble their memories.

This works out with a touch of the magic lantern, of an optics experiment to it. You get little disks of scenes, scrambled and warped, and you must use the triggers to move the image left and right, shifting it through various unspooling levels of chaos until it resolves. Do this enough and the scenes link together and give you a story - a story focusing on an object. And then you go and look for the object.

This is where the MRI stuff comes in. Each area in the game is a set of dioramas for you to pluck out and rotate. You can select objects within them and then...slice? In you go, sectioning through a wardrobe, a bedside table, a concrete wavebreaker, a head of lettuce.

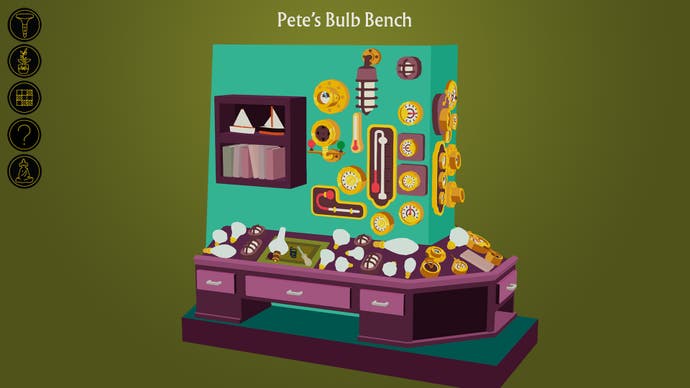

You're looking for the objects you've been sent to find, but really you're just looking. Human nature takes over. What's behind that? What's underneath that? What's inside it? Never has a game been such a glorious hymn to nosiness. And never has it rewarded in so many little ways. There is often a bit of cleverness involved in finding the big ticket items - go back to the story, where did it sound like that thing you're after might have ended up? - but there is a human logic to everything else that still manages to surprise and delight. A sofa will reveal a remote control down the back of it. That head of lettuce has a caterpillar inside! One of the characters who was once in the army had a set of boots that held a secret that made me understand him a little more when I found it. Other things are so universal that I ended up understanding everyone a bit more. This is a game about seeing - really, when you get down to it, you're just a reticule most of the time, roving, selecting, deselecting - but it is also built from seeing, from studying. Its dioramas reveal a lot of interesting human stuff: the way people treat things, the hopes they put into their possessions, the things they do not value enough. Someone's got booze stashed for when the shift ends. Someone has a secret business going. Someone's cheating at cards.

And beauty. Beauty everywhere. A tomato is its own little universe, revealing pulsing starbursts of seeds. A lightbulb contains the off-the-cuff New Yorker sketch that is its filament. A boot is home to a perfect spider. You reveal its presence and then guiltily seal it back up for some unfortunate to rediscover the hard way.

Once the items have been located - there is a second layer of objects to spot in order to collect a set of little beasties called Grenkins, and these require not just an object but a specific cross-section of it - it's time to round up the spirit of the dead and then talk to them. This is where your dog comes in, a lolloping Bob Godfrey hound, a long Cumulus cloud freshly lumpy after a tumble through stinging nettles. Once the dead re-emerge Morris can find out if they want the job - and it's never really a surprise, because by now this ghost is no longer a stranger. We have come to know them, through memories and through the things we have spotted rooting through their stuff.

What I love about these various systems is the way they sit together. Any game can be harmonious with enough craft, but it takes a special one to make such joy from its elbowy love of different things. Blending 2D and 3D art, blending MRIs and chandleries and Fresnel lenses, there is a sense here of Hohokum, a previous game from the same team that was always experimenting and never settling. Such a privilege to play! I Am Dead's individual pieces work together well, but they retain their discrete powers to fascinate individually. It is a game with the unmistakable feel of being pulled together from people's personal enthusiasms. It feels, as Hohokum did, like paging through a brilliant sketchbook filled with glittering ideas: restless stuff. It tells a story - and a good one - but it has retained a memory of the time when it was still a mood board.

And there's something else. There is no delicate way of seguing to this final point. When Joan Didion's husband died unexpectedly, she found herself keeping hold of a pair of his old shoes. Not because she had any emotional or nostalgic attachment to them, but because she knew that one day he might need them again when he returned to the apartment. I don't think Didion was talking about a resurrection here. I think she was getting at something - she calls it magical thinking - that is almost never really spoken about with death. Something that I Am Dead explores beautifully, and, to me, in quite a profound way. Death is awful, and it is also powerfully strange. There is a surprising strangeness, as wrong as that sounds, a disarming lack of logic as the mind tries to grapple with that kind of absence. There is even a quirkiness to the failings that can occur when the mind can't quite bring everything together again neatly. Death, amongst all its other qualities, is odd. Hard to get the head around. At times, and I am speaking from my own embarrassed experience, it feels both utterly final and also strangely permeable.

I never held onto anyone's shoes, but I had a university friend who died a number of years ago and lives on in my mind in the oddest ways. For a while, typically just after waking, I knew he was dead, but I also felt like I should talk to him about that the next time I saw him. I spoke to him in my head all the time - much like the citizens of Shelmerston - and these conversations seemed to have a natural shape to them, to lead somewhere and to surprise me. I still talk to him.

I Am Dead, with its ghosts, its world of objects, large and small, curiosities charged in some ways by the people who owned them, speaks to this very clearly, for me at least. It speaks of the ways that conversations with the dead go on. The way rituals and responsibilities take on new and perhaps confusing dimensions. More than anything it is a reminder of that bright contradiction - that death has absolutely everything to do with life.