I fell in love with Myst in 2024

Island memories.

I often think about how memory doesn't exist. Our past is, instead, a complex process of reconstruction. If I open a door my brain retrieves its name, shape, the sound it makes, and where it leads from different parts of my brain. As someone who often looks back wistfully on media from my childhood, I'm amazed that these disparate points collate into memories so vivid and affecting.

As I age, I'm forced to wonder, however, whether my changing feelings about the experiences of my youth are down to growth or simply errors in this reconstitution. How much does my brain mislead me about my own past? Perhaps the answer is best found in something that was concretely defined in my childhood. After more than twenty years, I want to talk about Myst.

I was two when Myst released in 1993. Its influence and importance were lost on me, even as it arrived in my house in the late 90s. Yet, while other games that chugged along on the beige Gateway PC, set into an MDF corner table that dominated our dining room until the mid-2000s, have remained rare bright spots in my youth, Myst haunted me.

It sounds dramatic - and I am being dramatic - but at a time when I might get a new game two, maybe three, times a year, games did have a more dramatic influence on me. By arriving so seldom, they became more formative. Myst stayed with me not because it inspired a particular feeling in me, but because it inspired nothing. I made no progress in the game. I didn't make it out of the first age. I'm not sure I even solved a puzzle. In a childhood spent in the grip of the Nintendo 64, Myst was frustrating, abstruse, and boring.

So what? We enjoy some games and we don't enjoy others. Yet, as I started to understand how foundational Myst is to adventure gaming, I kept thinking I should go back. It became one of those games; one of those that sit in your backlog, brighter than others. I always demurred. Memories of that dentist chair, those enormous cogs, and the weight of my complete failure to understand it even on a fundamental level intimidated me.

Even as late as 2023, subtle dread would creep from those distant points in my brain every time I considered revisiting Myst. When I told a friend about this, she insisted I just play it - if only to see how I reacted to a game she loved and fought through in the 90s. As someone who thrives on being told what to do (who wants to make their own decisions?), with nothing else to do in October of 2023, and with three whole English pounds to spare, I did just that.

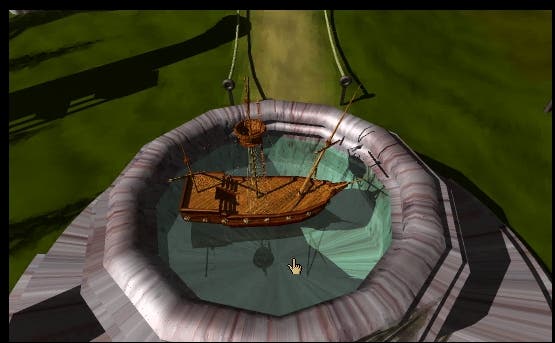

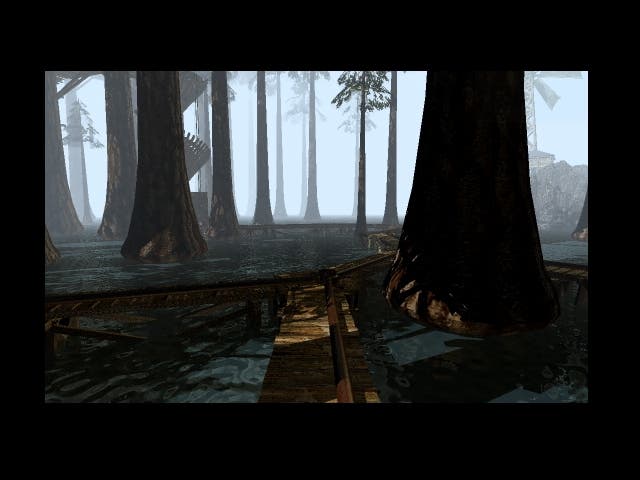

Myst is a surprisingly simple game beneath its complex challenges. You are dumped on a small island dense with puzzles and all the requisite information needed to solve them. There is no real push in the direction of that information, but there is an understanding that these puzzles lead to something. This is often another puzzle, building a steady rhythm as linear paths bisect the mysteries of each island - what the game calls ages.

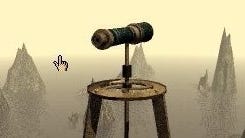

These puzzles often require lateral thinking, at times a good ear for sound, and solid memory. In 2023, this was aided by having a camera phone, but the free-roaming remake, which unfortunately removes Rand Miller's FMVs, does allow you to take in-game snapshots that it then squirrels away in its menu.

After years of dreading Myst, I was surprised to find myself moving smoothly through the game. Shockingly, my problem-solving skills had, in fact, improved since I was nine. I solved Myst's puzzles with a hitherto unprecedented skill and deftness - or, rather, I was adept at stumbling onto solutions in ways I was not supposed to. Presented with a table painted with a compass and surrounded by buttons, I tested one to see what might happen, only to land on the correct input. This caused the friend monitoring my progress to have a minor conniption. Later, when I didn't get stuck in a lift hidden in a tree - apparently a pitfall for many players - she told me, "You are Mister Magooing your way through Myst!"

In my defence, it wasn't all a fluke. I countered the dentist chair on my own, I intuited my way through Myst's infamous maze, and I understood what I was supposed to do with the table puzzle even if I didn't actually do it. Solving a puzzle in Myst, it turns out, is a lot like writing. You fumble around, assume you can't do it, and stare at the same thing over and over - whether that's a piano inside a rocket or a blank page. Yet, like writing, few things feel quite as satisfying as the moment when the solution comes together.

I breezed through Myst (and its sequel, Riven) and had a blast doing it. After years of writing the game off as beyond me, I had finally conquered it and the fear that my brain had inexplicably attached to it in years of rebuilding the memory. I started to wonder, what else had my brain gently lied to me about in a misbegotten attempt to protect me from my own past? Maybe I actually like celery, maybe I can swim, maybe I've been too harsh on Hideo Kojima. No, let's not take this too far.

I come from a family with a strong history of dementia. Perhaps that's why memory is so fascinating to me, because I know one day this baffling abstract concept we call remembering will be gone. It's scary, scarier than the memories of Myst that stopped me playing it. Yet, even as I worry about the connections that rebuild my past daily, Myst helped me understand them.

I completed Myst not because it's actually easy or I am just a talented gamer (I am not). I completed Myst because I now have a wealth of context on which to draw that helped me understand what I couldn't as a child. Those points, as abstract as they feel, are me, and I am a total of all the experience they store. Myst helped me understand that - a video game told me more about my memory than my past ever could. It turns out, I just had to find the right time - and the right amount of bullying from a friend - to learn that lesson, and learn to love Myst.