In search of the perfect bug

"A metal clanking sound plays if the user's character stabs the curtains."

There's poetry in games, but you often have to look for it. Sometimes the place where you have to look is in the patch notes. Take this example, now justly famous, from Boiling Point: Road to Hell, an open-world action-adventure that, back in 2005, was going to propel Arnold Vosloo to even greater heights of fame and influence following a nuanced performance in The Mummy. "Fixed: size of the moon," it reads. "Fixed: jaguar floats across screen at treetop level." And elsewhere: "Police station cannot be destroyed by a crossbow anymore." Fixed!

Like much great poetry, there's a touch of sadness to it. The whole thing might conjure a wistful imagined dialogue in the reader's mind. "I've sorted out all this stuff," the poet says, and I reply, why? That stuff sounded amazing as it was. Never fix the size of the moon. Never fix the flying jaguars or the police stations that are just a bolt away from exploding. Let Arnold Vosloo run free and unfettered in the only kind of open world that's capable of holding him.

Boiling Point's the exception rather than the rule, of course, and not just in the manner that it's willing to rely on the star power of Vosloo. It's a video game that's truly elevated by its bugs. For most games, the bugs aren't quite so helpful. I don't know anyone who plays Battlefield 4 and thinks to themselves, "Hey, these glitches and physics disasters and random disconnects are really adding something interesting here. I dig this." Bugs ruin games and erode goodwill. Yet part of me still wonders if that always has to be the case. In fact, many years ago I stepped outside on a frosty evening, stared up at the moon (far too small for my liking) and made a solemn, Bruce Wayne-like promise to myself: I'm going to find a game that's enhanced by its bugs. I'm going to become the Big Bug Hunter. I'm going to find the perfect bug.

Part of my reasoning for this was an inkling that bugs might be for games what editing is to cinema - the one irrefutable contribution an art form makes to culture at large that somehow remains largely specific to the art form in question. Books may have misprints and films may have audio glitches, but neither of them has proper fully-functioning bugs the way that games do. Most art's not reactive - not reciprocal - enough. It doesn't draw the audience into the dramatic space in such a weaponised manner as games can. It doesn't force readers and viewers to engage with its mechanics and become participants.

And, by extension, most art doesn't then blow up in its participants' faces. Anna Karenina does not suddenly hurl you 30 feet across the room whenever Levin makes an appearance, and Deep Blue Sea does not randomly render its audience as disembodied legs, dashing around and getting snagged on doorways. Only games can perform these miraculous feats, and if only games can do this, shouldn't there be some opportunity for greatness here? Couldn't the right bug speak eloquently of the inherent wildness of games, of their promise to drag their players through the screen and then shake them around a bit?

Nine years after Boiling Point, I'm still looking for the perfect bug. It's much harder than it initially seemed. Boiling Point's fun to think back on, but it's not that brilliant to play, even unpatched and filled with flying jaguars. Skate 3, another glitchfest, is great for YouTube blooper compilations, but I rarely get it down off the shelf. Over time, I have at least drawn up a few basic prerequisites for how the perfect bug might behave, though. I'm slowly closing in on my target.

My perfect bug is consistently funny, I reckon: funny enough that I laugh at it the 50th time it happens with the same eagerness I felt when I laughed at it the first time. It also walks a tightrope between predictability and chaos. It has to be predictable enough that I can rely on it to create unexpected tactics within the game world, but it has to be sufficiently chaotic to retain an ability to surprise and delight.

The perfect bug puts you in your place, too. I mean as a human being. In its bending of the accepted rules of a game, it reminds you how petty, how limiting, the accepted rules are. It judders designers out of their cloistered thinking: why must people walk everywhere? And why shouldn't cars be invisible, or permanently on fire, or playing the start menu music backwards out of their trunks? The perfect bug suggests that if games are dull, it's because we are dull, and we hem them in with our dull assumptions. The perfect bug reveals a game without its serious - its human - expression fixed on its face. It reveals a game left to its own thoughts.

Recently I've added a final prerequisite. The perfect bug has to be a real honest-to-betsy error. The game has to be broken on some entirely un-self-conscious level. No hipster glitches for me. No Brooklyn toast bar ragdoll pratfalls tailored for the front page of Buzzfeed. I'm after the real thing.

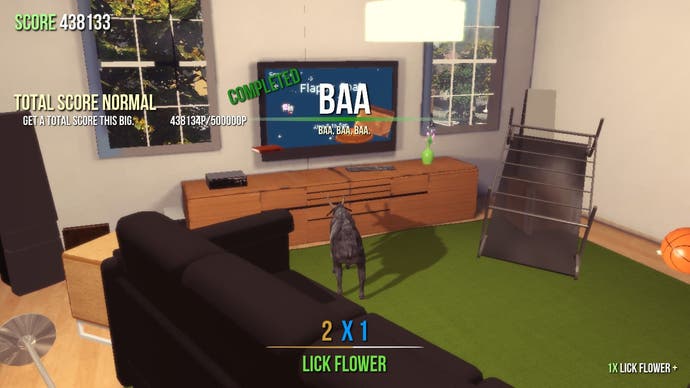

Enter Goat Simulator, a game I was very excited to play this weekend, not just because it offers the keys to a kingdom where an angry ungulate is in charge, but because its developers claim that, while they've fixed the truly game-breaking glitches, they've left all the other bugs in. Everything else that doesn't lead to an outright crash is fair game. Everything else is content.

And yet it transpires that playing Goat Simulator as a bug hunter is a quietly unfulfilling business. It's a little too easy to see the bugs, for starters. The game also seems a little too comfortable with their presence for them to be worth the finding in the first place.

Something important is missing here. You could call it the FIFA factor. The joy of an Impact Engine glitch - or so Eurogamer editor Tom Bramwell tells me - is that, most of the time, the engine in question's doing a laudable job of delivering footballers in all their realistic glory. This means that the sudden transition from elite sportsman to shambling pile of twitching, sneezing bone jelly has a sort of subversive delight to it. It's the thrill of the ground opening up and the uncanny valley swallowing you whole.

Goat Simulator's so haphazard by its nature and its inclinations that the bugs in it seem tamed by the experience, while the uncanny valley has little to mock. There's barely any established reality for bugs to subvert. The game's like a wildlife reservation for bugs, like a National Trust garden set aside for them to frolic in, and the hunt loses much of its lustre as a result. Not even an 18-foot goat tongue attached to a basketball can change that. Not even the bit with the petrol pumps and the trampoline, either, although, on balance, it was worth the time it took me to rig it up.

Even so, Goat Simulator has re-energised my quest for the perfect bug. It's made me realise that the chances of finding a really great bug grow stronger every day - and that this isn't necessarily good news for games in general. On the positive side, the chances for great bugs to emerge are improving because tastes in games seem to be veering from the scripted towards the systemic - to simulations and open worlds where bugs can really lend themselves to new strategies and might really do some tasty damage. Meanwhile, Early Access games are making all audiences more comfortable with the idea of playing something when it's still glitchy, unfinished, and often joyfully unpredictable.

I have no problem with that, but it would be nice if it was a state of affairs reserved for Early Access games. Just look at a handful of the big guns and their sometimes toxic relationship with online updates. Battlefield 4's not a paid alpha by any stripe, yet when it was launched it sometimes felt like one, and it has relied on post-release patches to knock itself into some kind of shape ever since. My perfect bug may lurk out there in the near future, then, but so do lots of the traditional kinds of bugs: the enthusiasm-diminishers, the progress-wipers, the bugs that will never ever be fun and just make you bitter.

Still I have hope, and I'm spurred on by some video game luminaries, too. Ages ago, I spoke to Billy Thompson, a designer whose career covers the likes of GTA and Crackdown. He told me that the main lesson he'd learned during his years as a developer was not to instantly rush in with a fix when he saw players doing something in one of his games that he hadn't planned for. Sometimes a bug is just a feature in waiting - a great feature that nobody human would ever have come up with.

Equally, speaking at this year's GDC, Robotron designer Eugene Jarvis argued that "some of the coolest features of a game can be bugs". What a thought! "You have to be skilled enough to make sure the program doesn't crash, but is buggy enough to have richness," he said. It was wonderful to hear that, because I've spent years trying to work out why Jarvis' games feel more alive than those by other arcade designers - why they're more vividly wriggly than Space Invaders, say, or even Asteroids. A lot of it comes down to the fact that Jarvis favours AI behaviours rather than set paths and scripting, but maybe some of that itself is enhanced by the glitches. Maybe it's the unpredictability that makes those behaviours truly exciting.

Oh, and as Jarvis mentioned at GDC, he came as close to the perfect bug as anyone, incidentally. Robotron. Wave 5. It's the first Brain level, and Brains are the guys who hunt down the high-score family collectables and turn them into deadly Progs. Except, in Wave 5 there's a bug that means that all but one of the family members generated are Mommies, while all of the Brains are hunting for the other one: the lone Mikey.

Every time I see this explosion of Mommies across the screen I want to laugh, and the tactics it encourages are famous in the Robotron community. Keep that Mikey alive, and reap the Mommy rewards. That's a pretty good bug, all told. Can games do better yet?