Inside Pokémon's house of cards

Behind the doors of Creatures Inc.

There's a part of me that wants to say the inside of Creatures Inc., the Tokyo company where Pokémon cards are made, is exactly what you'd expect. That it is everything you've imagined. A Wonkalike dream factory of wonder and weirdness, hidden in plain sight.

And in a way it sort of is. There's no grand entrance or giant, Pokémon branding; it's mostly one large, square room in a corporate, multi-use tower block, with a completely missable office door that when closed blends, quite impressively, into the charcoal walls of a corridor. It swings open to a sparkling white, hi-gloss lobby that sits in perfect contrast the exterior, the Creatures logo, magnetic, on the wall in front. It's probably not even intentional, but still. You get the effect.

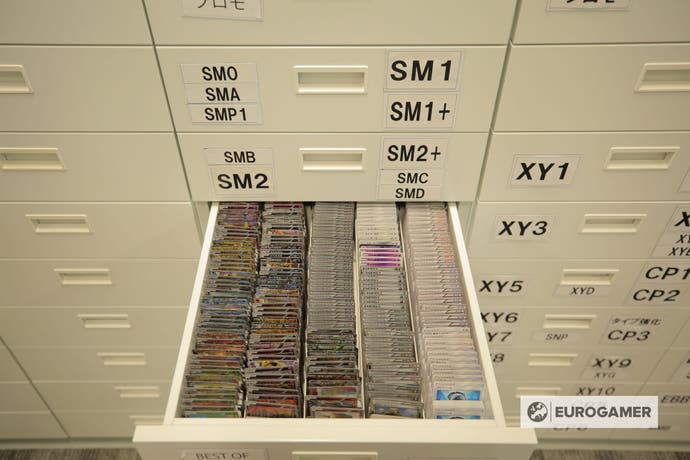

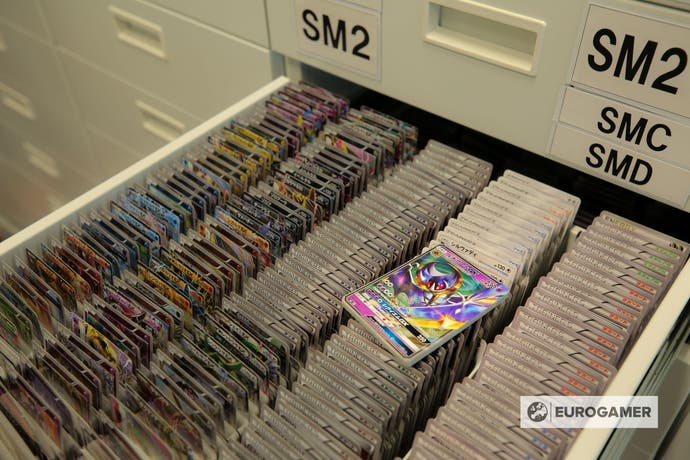

The reality, obviously, is that Creatures inc. is just an office. There are a few tells - in the lobby a lanky, long-necked Alolan Exeggutor blends in with some houseplants; at one end of the main room is a wall of bland, office-grey filing cabinets, but instead of stationary inside it's what must be tens of thousands of Pokémon cards - every one ever, at least since Creatures began, after the old Wizards of the Coast license was taken over in 2003 - organised immaculately, row by row.

There are a couple of board rooms. I sat down for an interview with Atsushi Nagashima, Game Director of the Pokémon Trading Card Game, in one of them, and while I'm joined by the usual crowd of PRs and assistants, I'm also join by the board of Pokémon - as in, a board of directors made up of actual, large Pokémon plushies sitting at the conference table. Even Nagashima himself is in on it, I think - obviously an important man, po-faced and suit-clad in official photos provided by the Pokémon Company, but really light-hearted and affable in person, always with a wry smile. You get a sense that, like everyone else at Creatures, he's really a kid on best behaviour, the ringleader who gets told to tour parents around the school - and to tuck in his shirt while he's at it.

To really hammer that undercurrent of oddness home, at one point, just when everything's at its most normal, we're visited by a man called Tomokai Imakuni. Imakuni, if you played the card game way back in the day, is that weird man, dressed in a mouse costume - or maybe a bear? - on the Imakuni? Trainer Card from the very first set, that just confused your own Pokémon if you played it. He also makes a particularly nightmarish appearance in the Game Boy version of the TCG - something that I thought I'd managed to expunge from memory, until now - and he is something of a living legend, only turning up in the office from time to time.

"I kind of try and get a sense of a story... this Pokémon is living in the real world, it's doing something. It's thinking something" - Mitsuhiro Arita

Apparently, the mouse-bear outfit is what Imakuni likes to wear to karaoke - he's a singer, by day - and he keeps it in a drawer by his desk at work, presumably to just pop it on for giggles when the mood strikes. He is much less nightmarish in person.

Back in the real world, Nagashima tells me that work starts on a new expansion set of Pokémon cards "about a year ahead of release," and likewise often long before a video game with new Pokémon comes out, in which case the freelance illustrators who normally do things on their own terms (and even still submit artwork in its original hand-drawn form) will work in-house, at their own studio space, for the sake of confidentiality.

I always wondered how much of a hand Game Freak, the studio behind the main series Pokémon games (and the place where Pokémon themselves are first designed) has a hand in the cards - or if they even have one at all.

"In the beginning, it's very important that we have a lot of back and forth with Game Freak, really deep dialogue" he explains, "so for example with the creators at Game Freak, Mr. Sugimori or Mr. Masuda, to really get their thoughts, their philosophy behind the game, what they wanted to accomplish or express with the games, and really kind of process that before we begin work on the cards." After that, it's pretty much Creatures all the way.

A lot of the day there is spent figuring out just how the whole thing works. There are about 40 full-timers, and another 70-odd who work freelance on the card game in various ways. Roughly half of the full-time staff are playtesters, headed up by Quality Management Leader Satoru Inoue, who spend seven hours a day, 11am to 8pm, playing the game.

"It's not the case that we only have experienced players here - actually in my case I actually had no experience whatsoever with Pokémon TCG before coming to work at Creatures. But obviously after entering the company and playing it seven hours a day, you become a pro player," he explains. "It's really just a requirement that [the playtesters] like Pokémon and they have an interest in other card games, even if they don't have any particular experience with the Pokémon card game - perhaps they'll just be collectors as opposed to players of the Pokémon TCG."

The playtesting room is noteworthy precisely because of its blandness. It's just a glassed-off rectangle at the end of the office, only the back wall is spanned end-to-end by that grey cabinet of archived cards (they told me after we'd left that, actually, a load of the cabinets that were unmarked and assumed empty were actually full of new cards they were still testing, but didn't want us to go nosing around in). When you open the door you're most affected by the sound. A sudden blast of it - half a dozen people shuffling cards, very quickly, at the same time - that sort of squirts out of the soundproofed room like air from a vacuum.

They test a range of things, of course - a card's impact on the meta, its 'data', like its HP and evolution requirements, the strength of its moves, and so on. Inoue gives an example of Tapu Lele, who had to go through a number of iterations before reaching a passable form. Its ability once let you take two supporter cards from your discard pile at will but, as would probably be unsurprising to a decent TCG player, "it was actually really not working out well for the game balance" so they changed it, over and over, until they settled on what it is now.

As well as those intricacies though, something Inoue also mentioned in passing was that playtesters are keeping an eye on a card's "personality" as much as they are its stats. It's hard to really feel that's too profound when you're sat next to a life-sized Wobuffet, but it struck a chord, at least, and was actually something of a theme in how the developers at Creatures spoke about their work.

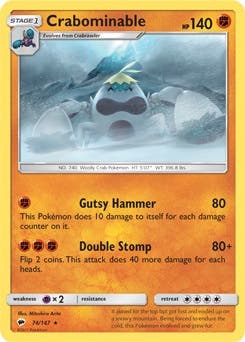

Later on for instance, back with Nagashima, it's mentioned a few times - in how designing a card like, say, Crabominable, requires them to think about the nature of the Pokémon - "this kind of scary-looking, powerful type of thing" - but also how you scale that down, to two moves and a picture on a piece of card. "Expressing that Pokémon's personality, like through HP or its attacks - how to express that kind of strength of something - is kind of how we begin the creative process."

He talks about how the first time a Pokémon is shown in card form is, understandably, the most important, but particularly so because they're so hopeful that it "provides the opportunity that kids can get to know the character," and how later cards for that Pokémon - think Surfing Pikachu or Dark Gyarados, or just the many second or third versions of cards with more playful illustrations - give the chance to "show off a different facet of that character, that maybe hasn't been seen before".

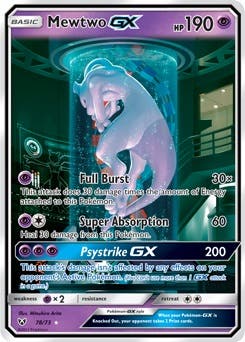

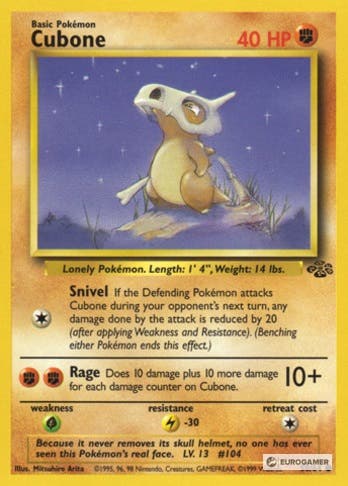

Character and personality are words of the day, then, but no more deftly applied than when I talked to Mitsuhiro Arita, the illustrator who almost certainly drew your favourite cards from childhood - like Charmander, Charmeleon and Charizard, the original chunky Pikachu, gormless Magikarp and mighty Gyarados, and a personal favourite of mine the tragic, forlorn little Cubone.

I might as well be honest: I am enthralled by Mitushiro Arita's illustrations. Probably excessively so, but I find his the most evocative work of an already evocative medium, from an already evocative memory at an evocative time of my life. It's an easy win.

Arita's work is, consistently, a work of conjuring - a summoning of another place into existence and a squeezing down of that place into about twelve square centimetres of paper. I'm transported by it, in an oddly specific way, that I haven't been by any other illustration - at least without the help of score and motion and voice, that elevates animation from paper to film - and I'm infatuated with the emotion that comes from looking at it, the intense sadness and longing of seeing a place you feel you remember with absolute clarity, but have never visited, and can never go. Pokémon cards always do this for me because they're Pokémon cards, and I'm certain they do it for millions of others, too. But Arita's, for some reason, do it even more.

We talk for a while, again, just practically, about how everything actually works - I am frightfully aware of the fact that asking about my (over) reactions to his drawings, and his intentions, is just as likely to be met with a veneer-shredding shrug as it is some moment of pure reflection. Or that all this lofty chin-stroking stuff just won't translate, in the brilliant absurdity of a room full of both serious people in suits and stuffed Pokémon on board room chairs - and so, at least at first, we stick to the expositionary stuff.

"At first I'll receive contact from Creatures saying you know "how much time do you have to work on different cards, how many do you think you can handle?" and then after I've replied to that they'll say "okay specifically we'd like you to design this, this and this Pokémon". And then they'll send over some reference data, for me to look at when deciding on the design, and they'll be instructions such as "we want the background of the card to look like this, we want it to be this kind of weather or this kind of season", or sometimes even "we want this Pokémon to be using this specific move or taking this kind of general pose," and then based on that I'll write up a rough draft, and then go over the rough draft with Creatures."

"In total it's about seven weeks that we're given from start to finish for the card design. But then half of that seven weeks will be the time that it's over at Creatures being looked at, being checked, and then the other half will be actually me working on it."

In other cases, he explains, like back in the early years of the game, they could have more fun with it - he shows me an Ursaring card he drew, of the towering bear-like creature taking a bath in some hot springs, that seems a long way from the literalism of scary Crabominable. And then a Krabby - quite literally a grumpy crab - that he drew with a claw raised to its eyes, wistfully pondering the horizon as it looks out to sea. A crab. Pondering the sea.

Even better is Umbreon - a Dark-type, nocturnal evolution of fan-favourite mascot Eevee - that he drew two variants of, both resting on a kind of Parisian rooftop, that I hadn't actually seen before. He drew one in the day, with a soporific yawn, the bustling city behind it; the other on the same roof but at night, all feline predator, your tabby that thinks it's a lion. "Apparently that was really really popular with cat lovers. I got great feedback on that."

I ask him about his style, now that we were on the topic, and the same points come up - character, personality - but also a little more. "I kind of try and get a sense of a story, so that the players can imagine, you know, this Pokémon is living in the real world, it's doing something. It's thinking something. There's a world outside of the frame of this card here" - and, yes, he talks about that mournful Cubone. "With Cubone as well he's just kind of standing there, but you get a sense of his background, and his story, and it's not just the framework of the card."

"So, really as a philosophy, it's more getting across the feeling that they're living creatures, that they're doing something, they're feeling something."

We chat a little more, and someone suggests he shows me some of his sketches - his own sketches, not for Pokémon - and he does. In a little A5 notebook he flicks through pencil drawings and scrappy pen outlines. Watercolours of the passing world that he does on the tube, with a little palette made from a converted business card holder (there is something poetic here about the playful kids at Creatures, and their flying in the face of stiff Japanese business culture, but I'm nowhere near capable of indulging in it). He shows me some more - early blossoms in a freezing park; empty chairs in a hospital waiting room - and there's that nostalgia, the elephant in the room whenever Pokémon cards are involved, even then. The longing for places that I've never been. But maybe it's just me.