It turns out FIFA is ideal for teaching mental health patients about resilience

The beautiful game.

It's clean, bright and open. There's colourful art on the walls, the lingering but not unpleasant scent of toast, a fish tank bubbling away at the front desk.

A mental health unit looks just like a run-down Travelodge. It's a quiet place for people to get respite from unfair, unstable, unsupported lives, somewhere to learn some sustainable coping strategies. I worked in this unique setting for quite a few years, and it was there that I learned how FIFA can build resilience.

I thought I already knew all about resilience. It had been drummed into me from an early age, from the magical resistance spell in Dungeons & Dragons to the resilience stat in World of Warcraft. It was intrinsic to card-battling and choose-your-own-adventures. Games had been teaching me about the need for a valid defense against the perils of the world, a magic suit of armour. I guess I hadn't been listening closely enough.

We had a PlayStation on the ward. Some patients used it to while away the long night hours, others felt it was a small but meaningful connection to their lives outside of hospital. Lots used it to watch movies in between more structured activities and therapy sessions. All this stuff was great, but we, the staff, were not thinking about how to harness this incredible machine. Which was silly, really, considering we used practically everything else as an opportunity for care.

FIFA was by far the most popular game. It was the first game most people chose from a fairly extensive collection, and it was the one that held their attention longest. We didn't think about this either. Again, silly.

The idea came from a patient, which is how most good things in the NHS start. He was unassuming, almost shy. He was a bricklayer, but found the lack of regular work stressful. His housing conditions were someone's idea of a sick joke. He found it hard to make meaningful relationships and felt depressed about his lack of friends. He struggled to regulate his emotions. He grew up in the care system, moved around a lot. Nobody had ever taught him how to make friends, how to experience emotions without becoming overwhelmed. It was a horribly familiar story.

This patient was participating in a 'personality disorder clinic' that I was facilitating. I was talking about Dr Martin Seligman's theory of resilience and he looked past my awkward phrasing and overlong explanations and got straight to the heart of the matter:

"It's just FIFA though isn't it?"

Back of the net. Someone hand this man a slice of orange and a trophy because, boy, that's the match winner right there.

Of course it's FIFA.

Seligman's theory of resilience uses positive psychology. It looks at what makes happy people so happy, whereas conventional psychology tends to focus on problems, issues and symptoms. The key points of the theory are easy to grasp and simple to implement. They are also what makes FIFA feel so great to play. You could argue that they've been there since the first iteration, way back in '93.

Here's a summary of the core concepts Seligman suggests that an activity needs in order to encourage resilience:

Positive emotion: this can only really be evaluated objectively. In FIFA, it is evident in the warm Ready Brek glow of victory, of a spectacular goal, that little bump of endorphins when you latch onto a perfectly-weighted pass.

Engagement: this is the flow-state you experience when doing something challenging but not overwhelming. Like stitching together successful crosses, tense one-on-ones with the keeper, or tika taka, those moments where you're locked in to the action. Ever been shocked by an unplanned four-hour gaming session that just sort of happened? You were floating on the flow-state, my friend.

Relationships: even when playing alone and offline, FIFA always keeps you aware that you are just part of a team. You exert some, but not exclusive, influence on events. You build friendships with people sat next to you, or all across the world.

Meaning: belonging to, or serving something bigger than oneself. In FIFA this could be participating in a league, tournament or 'The Journey' campaign mode.

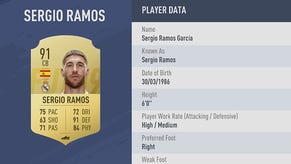

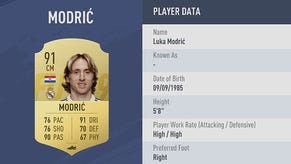

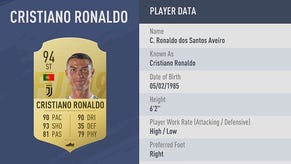

Achievement: This is the big wins, improving skills, realising potential. You can sometimes pay to cheat this aspect, for example via player card packs. Doesn't quite feel the same though, does it?

You might make the case that other games fulfil Seligman's criteria, and you might be right. But football is arguably the world's most popular sport. FIFA's controls are intuitive, and other games don't benefit from the collective language of an international obsession. RPGs are too fiddly, action games often take a while to settle in. You can start a match of FIFA in no time at all. It's great for people who want to play together but aren't able to communicate verbally, making it invaluable on the ward.

Dr Jennifer Tichon and Dr Timothy Mavin have studied the effects of playing video games on people's sense of personal resilience. Their paper, published in the academic journal 'Social Science Computer Review', explains how people reported feeling "...more confident in their abilities. Many also associated themselves with the same resilient traits as their characters display in games. A range of popular off-the-shelf video games were reported as helpful in providing players with the opportunity to feel confident under pressure and, importantly, some players reported transferring these positive psychological effects to their real-world lives."

Research on the positive effects of playing games is still lagging behind advances in technology. Moreover, many of the recent investigations have been concern-focused. It seems we're still just trying to find problems, instead of looking for solutions. Concern-focused research is what gives us headlines like, "Fortnite turned my child into a zombie". Open research and collaboration leads to beautiful attempts at representing mental health issues, like those found in Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice, Elude and Aether.

Back in the personality-disorder clinic and I could sense one of those subtle alignments in the group. Nothing as dramatic as a breakthrough, more like a little nudge in the right direction. Something cool was about to happen.

"If FIFA is so good for us, what should we do about it?" I asked.

"Let's have a tournament," he said. "We can make posters for it. And you can bring us in popcorn and chocolate and snacks. And a prize."

So we did it. We got a whole bunch of staff and patients to work together. We got permission to use the big projector in the conference room. It felt like an old-school LAN party, lights down low, snacks everywhere, people oohing and ahhing. It created a close little community of activity, gave people real, tangible goals and engaged them in a common cause in a completely organic way. I felt like I was watching this beautiful thing spreading roots.

As time passed, FIFA continued to be the most popular game on the ward, and the one that I most often picked when trying to engage with somebody new. People who initially struggled to engage with each other became friends, people who felt isolated found common ground, people with distressing symptoms found moments of respite. That irresistible blend of accessibility, therapeutic value and fun helped me to initiate meaningful dialogue with many people that would otherwise have kept to themselves. It really is a beautiful game.

I got knocked out in the qualifiers, by the way. It was the first time I'd ever really been happy to bow out of a competition early. I was content to watch this thing unfold, to see the looks on their faces, flood lights shining in their eyes.

(To respect people's right to privacy, some personal details have been changed.)

Further reading:

Tichon, J. and Mavin, T. (2016). Experiencing Resilience via Video Games. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), pp.666-675

If you are worried about your own mental health, you could talk about it with somebody you trust, contact your GP, or search the web for local mental health services.

The Rethink advice and information service is available on 0300 5000 927 (10am-1pm)

You can call the Samaritans anonymously on 116 123.