John Carmack and the Virtual Reality Dream

VR is back - and it works! We chat to id's mad professor and try his amazing homebrew headset.

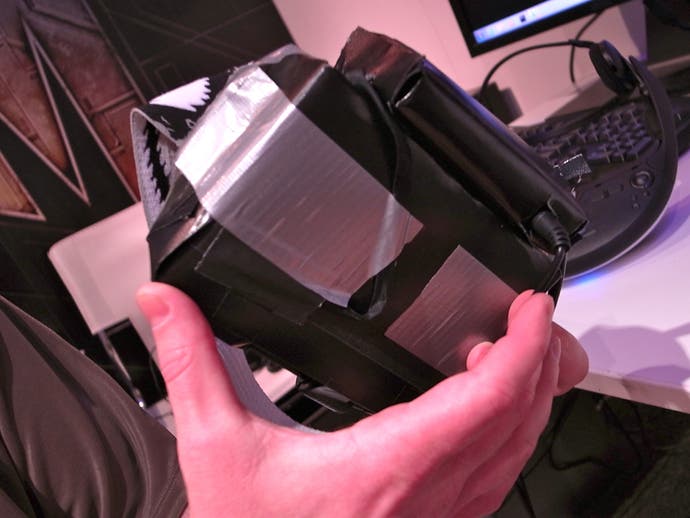

It was, to be frank, the best E3 appointment I have ever had. Today I met id Software founder and legendary coder John Carmack and tried his bonkers homebrew virtual reality headset.

The headset's not a commercial product - not yet, at any rate. It's a prototype kit which Carmack has modified himself and written firmware for. It's being demonstrated at E3 to promote Doom 3 BFG Edition, and I got to play the game using the headset for a few minutes (it would have been more if I hadn't been so engrossed chatting to Carmack about it).

The headset has a motion sensor stuck to it to allow it to track your head movements. Inside, a single, smartphone-style 6" LED screen displays two images seen through two lenses (which Carmack has masked off with black tape), providing a stereoscopic 3D view. It's held together by a ski goggle strap and some gaffer tape.

Carmack talked to me about the unit - and the improvements it makes to previous VR head-mounted displays and current personal 3D viewers such as Sony's HMZ-T1 - with infectious enthusiasm and in head-spinning detail. There isn't time to relate all that here (and some of it went over my head), but I've uploaded the audio of our chat for Digital Foundry's Rich Leadbetter to pore over.

In summary: Carmack has always been interested in VR, but dismayed by the poor quality of the options available. Recently he felt that technology was finally catching up to the VR dream, but improvements still needed to be made. So he set to work, concentrating in particular on reducing latency in the motion tracking, improving frame rates, and increasing the field of view - all essential, he believes, to creating a real feeling of immersion in a virtual world.

For example, the HMZ-T1 offers a 45-degree viewing angle, creating the impression of a 3D screen floating in space in front of you. Carmack's device has a 90-degree viewing angle, almost fully encompassing your forward field of vision. It puts you inside the image.

As he worked, problems that have dogged the VR world began to fall before Carmack's famed software engineering genius and simple passion for programming. His interest in rocketry - as founder of Armadillo Aerospace, he intends to build a commercial orbital spacecraft - came in useful on the latency issue in particular.

"There's a lot of work that you have to do to filter and bias the sensors and drift it to a gravity vector, and the baseline way [other VR companies] had of doing it had about 100ms of latency, huge extra lag on the sensors there," he tells me, somewhere in the middle of an unstoppable torrent of words. "So what I did is, I went down to the raw sensor input, and I actually took the orientation code that I did at Armadillo Aerospace years ago for our rocket ships... I pulled that raw code over and it got a lot better."

There you have it; it actually is rocket science.

So what's Carmack's contraption like to use?

The headset is incredibly light - weighing not much more than a regular pair of goggles - and quite comfortable to wear, although you can't wear it with glasses. Other than adjusting the strap, there's no tweaking needed to set it up comfortably. It's much more pleasant to wear than the HMZ-T1 (which Carmack has to hand for a comparison).

The 3D effect is perfect and, naturally, free of ghosting. The screen is quite low resolution, which is made more noticeable by the fact the picture is expanded to fill your whole field of vision, so unfortunately the image looks a bit crude. But Carmack expects there'll be 1080p screens available in the appropriate size soon enough.

As a 3D viewer, it's striking. But the head-tracking is something else. It's no exaggeration to say that it transforms the experience of playing a first-person video game. It's beyond thrilling.

Your gun remains pointing 'forward', and movement and aiming are controlled in the normal way with an Xbox pad, but you can look all around you at any point. You can check corridors to either side for approaching enemies. You can spin around to look behind you when you hear a noise. The speed and accuracy of the tracking are sensational and the increase to your situational awareness in the game is exponential.

It's best played standing up, so that you can move freely but also because it just feels more appropriate. There's a bit of a disconnect between the incredible immersion provided by the headset and the suddenly rather clunky-feeling pad controls - especially when moving through doors, when you instinctively want to lean around the frame.

But, overall, it's incredible fun. Doom 3 is an eight-year-old shooter, but in this form playing it is as visceral and exciting as it must have been to play the first Doom the day it was released. Just don't move around too quickly after you take the headset off.

VR was a technology before its time that couldn't live up to its promises, and it has subsequently become an unfashionable laughing stock. But Carmack is unapologetic about his pursuit of the VR dream. In fact, he argues, immersion in a virtual reality is at the core of first-person gaming.

"All that we've been doing in first-person shooters, since I started, is try to make virtual reality. Really, that's what we're doing with the tools that we've got available. The whole difference between a game where you're directing people around and an FPS is, we're projecting you into the world to make that intensity and that sense of being there and having the world around you... So the lure of virtual reality is always there."

And John Carmack is the man to make it real. His headset isn't a product, and maybe it will never be. For now, it's just a publicity stunt to promote a re-release. But it's the best kind of publicity stunt, as far as you can get from the booth babes and booming braggadocio of the rest of E3 2012. It's a brilliant man showing you his vision of the future, and sharing his bottomless passion for the possibilities of games.