Keith Stuart on: Influences

From John Ford to Frank Zappa.

When I was a young kid first discovering video games in the early 1980s, I used to go to the huge Wythenshawe library in Greater Manchester, where I could rent Commodore 64 titles for 10p a week. Usually, I went home with piles of fighting games and shoot-'em-ups like Yie Ar Kung Fu, Green Beret and 1942. But one day, when someone had been in before me and grabbed all the popular stuff, I glumly picked up all that was left: a copy of Deus Ex Machina, the bizarre multimedia art game by Mel Croucher about the birth of a living organism within a vast computer. I was 12. I wanted to shoot stuff, I did not want to watch a fetus gestate in a databank while Jon Pertwee narrated a story about a mouse poo. But I played it anyway.

It blew me away.

I had no idea a game could actually be about something, that it could be so weird and philosophical. When I saw an interview with Croucher in Zzap or some other ancient magazine, he mentioned two major influences: the music of Frank Zappa and EM Forster's short story, The Machine Stops. The next week, I went back to the library and rented a copy of Zappa's Hot Rats album on tape, and took out a Forster short story collection. The latter was an absolutely seminal moment in my life as a book reader, the former scared the absolute shit out of me. I never forgot either.

This year is my 20th in video game journalism - and it has got me thinking about that formative experience. Throughout my career, I've probably visited over 200 video game studios and interviewed over 500 artists, designers, coders and producers. Wherever I've been, whoever I've spoken to, the same influences have tended to come up. Very often they're from within the games industry - epoch-shattering titles like Super Mario Bros, Castlevania or System Shock. Partly this is to do with how immersive and all-encompassing games are - they suck hundreds of hours out of our lives, and we tend to move from one to the next in these great paroxysms of obsessive play. But also it's about the fact that games are different from other art forms - they are interactive, they are about systems and mechanics as much as they are about narrative and aesthetics. Consequently, developers are often as inspired by a certain double jump, or combat system or some quirky genre trope as they are by a story or visual element. Games are inward looking by design.

But even when mainstream studios - especially Western studios - peer outside the industry, they seem to draw from a very small homogenous selection of cultural influences. Star Wars, Star Trek, Lord of the Rings, Aliens, Bladerunner, Batman, Spider-Man - these are the posters, the action figures, the reference manuals that I've seen on the walls and shelves of studios everywhere I've been from Santa Monica to Stockholm.

I started to wonder - is this really all that game developers think about? Is there a sort of cultural maxim: get enough twentysomething geeks into a room and they eventually reference the M41A Pulse Rifle? Am I being a jerk just thinking that?

So at this year's E3 expo in LA, I made a point of asking every major developer I spoke to what influenced them beyond games and beyond the usual set texts of blockbuster game production. And of course, I discovered a wealth of diversity and a vast curiosity about the world. For Bethesda Games Studios, for example, the art of Norman Rockwell was a defining influence on the look of Fallout 3 and 4. The great chronicler of American life, who so beautifully captured the essence of the post-war era with its diners, smartly dressed working men and big beautiful cars, provided the singular nostalgic flavour to the game's apocalyptic landscape.

But for studio director Todd Howard, when his team discussed Rockwell, when it talked about the use of 50s Americana in its designs, the interesting thing is, they weren't necessarily thinking about just ripping off the visual style. It went deeper. "We look at mood pieces a lot," he says. "Whether it's a Rockwell painting or an old sad, song - they put you in a certain mood.

"We also looked at old John Ford movies a lot for Fallout 4- we studied how cinema can capture a space, which is very different from a game. Again, his shots put you in a certain mood. There is a tone. As a designer, you must always look for tone. You decide, how do you want the player to feel? Then you look for things that have that tone and you just stare at them."

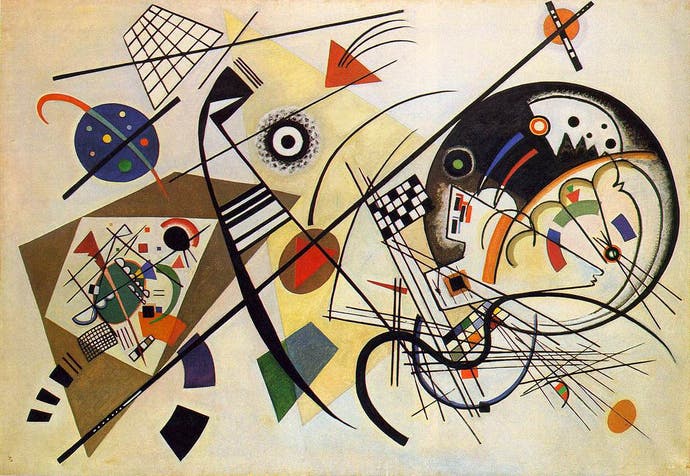

What I found is that the really interesting studios are the ones that mix and match distinct and diverse influences in this way, to create a whole new palette. The Japanese designer Tetsuya Mizuguchi, for example, was fascinated by the work of modernist artist Wassily Kandinsky who is thought to have had the condition known as synaesthesia, allowing him to literally hear colour - he wanted his paintings to somehow express this musicality. Mizuguchi spent years wondering how he could explore this concept in gameplay form and eventually combined Kandinsky's gesamtkunstwerk ("synthesis of arts"), with his other great love: club culture. The result was Rez, a game in which you convert action to sound, building the game's thumping techno score as you traverse levels and defeat enemies.

The key thing is, all studios draw from a vast array of influences, but in my experience, the really interesting blockbuster games are created by developers who allow those more esoteric elements to guide, not just a few teeny art decisions here and there, but the whole feel and purpose of a game. If you think about BioShock for example, the game is fundamentally about Ken Levine's fascination with Objectivism, the philosophy put forward by Ayn Rand which posits that selfishness is the defining human trait and government should stay the hell out of the way of ambitious people. Rapture is a vast Objectivist experiment, instigated by Andrew Ryan, and its bold, heroic art deco architecture accentuates his obsession with power and individuality. Even if the player picks up on none of that, they understand that this is not a world influenced by Star Wars or Bladerunner.

This combination of diverse influences also led to one of the most beautiful and haunting console games over the last decade: Journey. The team at ThatGameCompany were heavily inspired by the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, an important influence on the surrealists. His works often feature barren landscapes and deserted towers, usually with vast shadows and muted ochre tones, creating a sense of quiet desolation. His style is clearly evident in the sun-burned landscapes and ruined temples that we see throughout Journey. We have seen other developers drawing architectural ideas from artists. The geometrically impossible buildings imagined by MC Escher were a huge influence on both Echochrome and Monument Valley, while the complex and nightmarish 'imagined prisons' painted by 18th century Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranes were surely studied by the team at From Software when devising the fiendish citadels of Dark Souls.

At ThatGameCompany, the small team combined the potentious minimalism of de Chirico with something else. "I love Akira Kurosawa's movie Dreams," says Robin Hunicke, the producer of Journey, now CEO of Funomena. "It makes a statement about what it is to be human, about processing pain, separation, the threat of death, the beauty of life. It's about the decisions we make, the unknown and the unknowable. It's just a beautiful involving film.

"With Journey, we studied the dream of the Blizzard, where the climbers are on the mountainside and they're barely making it to camp, and the wind goddess (the Yuki-onna of Japanese mythology) comes out and tries to lull them to sleep. We looked at this as a team and I was like, this is what we've got to get into the final scene of Journey. I wanted to make people feel the sense of tenuousness between yourself and life."

Hunicke also agrees with Howard about the importance of mood and tone when looking for inspiration. What Hunicke loves about Ford are the great moments of silence, the sense of vast emptiness in the American west. "My favourite film of all time is Solaris," she says. "I'm a huge fan of almost no dialogue cinema - I will watch any film that has almost no dialogue. Mad Max for example - I was like, yes, they're barely speaking, this is so great!"

Elsewhere, we're starting to see how more games are reacting to the world outside of the arts, drawing inspiration from politics and wider society. This is most obvious in the indie sector where developers can experiment with offbeat ideas - like the border guard simulator Papers, Please. But these concepts are permeating mainstream titles. David Braben, for example, has often spoken about how Thatcherite politics influenced his space trading sim Elite and its emphasis on making money whatever way works best. For Elite Dangerous, with its more complex narratives of warring galactic civilisations, he looked wider afield.

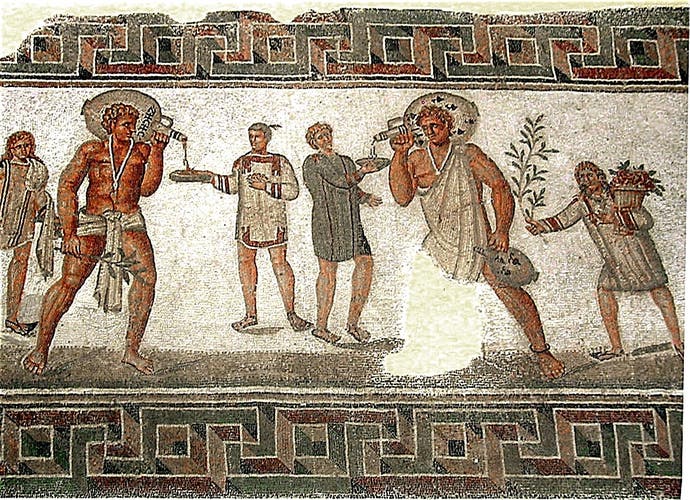

"Roman politics fascinates me," he says. "Nowadays, we are in a mindset where the only solution is democracy. But having to create different societies I read a lot of Roman literature, specifically about the system of patronage, and used that for the Empire. I love the contrasts it creates. Imperial slavery, where you sign up for a period of time as a slave for money to pay off a debt, which happened in Roman times, is actually very similar to signing up to the military. That parallel is interesting. People accept military service yet slavery is seen as abhorrent. There was a lot of literature at the time discussing systems like that. It has some really bad downsides, but also some obvious upsides. It's a very different system."

Harvey Smith, who worked on Deus Ex and is co-designer of Dishonored, acknowledges the cultural homogeneity of game development in the west and has his own way of bringing in different influences. "It's always gratifying to do something like travel to place you've never imagined before. I went to Saudi Arabia for a month and came away changed - you inevitably hear some snippet of something - good or bad. Like, prayer time happens several times a day there, and when the Saudi shopkeepers go to pray, many of them lock up their shops and make their Pakistani workers go out and sit on the kerb, they don't trust them. You see something like that and it stays with you - and when you're working on some game component, you're a different person - a different designer - because of those experiences. There's a guy on our team from the Ivory Coast, and he has stories about growing up, the things he saw and what he went through - you can tell his work is really influenced by that."

So yes, I've been a jerk. I'm guilty of making that facile generalisation that small indie studios have all the wacky influences while bigger studios just watch Ridley Scott flicks and read Marvel comics. It's not like that. However, it's only a small number of big studios that have been able to truly explore and exploit their more diverse influences. I think as games progress as a medium, more will have to look further afield in this way, discovering new ideas and combining them. When I've written about the lack of cultural diversity in blockbuster games in the past, lots of commenters have said, well they're responding to the market, that's what people want, so they make it. But culture is much more circular than that, and great artists do have the capacity to shape mainstream entertainment. We saw it in Hollywood in the 70s, when filmmakers like Scorsese, Coppola and Hal Ashby brought their auteur sensibilities to mainstream audiences; we saw it in music in the 1990s, when Hip Hop culture basically staged a coup on the pop charts.

Influence matters. The things we take in, the experiences we have, all shape us as people and creators. And video game players, far from being the narrow-minded geeks they're often portrayed as, are actually among the most sophisticated audiences in the world. Look at Metal Gear Solid 5, a game that combines stealth, action, politics and sexuality - with its seamless mix of the serious and silly, it is far more tonally challenging than almost any mainstream film of the last 30 years. If there was ever a time for a new blockbuster mash-up of Frank Zappa and EM Forster, it's probably now.