Keith Stuart on violence in crime fiction and video games

Oof.

In 2007, game developer Clint Hocking wrote a hugely influential essay about the problem with video games. Entitled Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock, the article looked at Irrational's classic shooter and saw in it a terrible contradiction. While the interactive (or 'ludic') sections of the game require the player to be selfish and powerful, the story sequences seek to cast your character as a selfless aid to the revolutionary leader, Atlas. As Hocking wrote, "By throwing the narrative and ludic elements of the work into opposition, the game seems to openly mock the player for having believed in the fiction of the game at all." Openly mocking the player is... not considered good form.

Another popular example is the Uncharted series. From the outset, the story encourages us to see lead protagonist Nathan Drake as a loveable rogue with a cast of charming friends. However, the Nathan Drake that the player controls is a serial murderer who guns down hundreds of "enemies' without thought or consequence. Indeed, in video games, players are very rarely asked to deal with the consequences or ramifications of their actions. Okay, a few titles have toyed with the concept, introducing polarising 'morality' systems that tot up 'good' and 'evil' actions. But it's rare that the ludic and narrative elements truly tie in to create a system in which player culpability makes any sense whatsoever.

At the same time, gamers are often surprised when non-gamers write off the whole medium as violent and stupid.

This happens to me a lot. At the Guardian I have the fascinating luxury of being able to write comparatively in-depth articles about games and then have them seen by a huge 'mainstream' audience - many of whom are not gamers. Often, in the comments section, below articles on titles like Call of Duty and Bloodborne, people will write things like "Just what the world needs, more violence". This always fascinates me because, well, violence has been an integral element of entertainment since the dawn of civilisation. Violence and retribution provided the fuel of the ancient Greek theatre, where playwrights sought to engender 'catharsis' - a sense of purging relief - in the audience by depicting the terrible crimes they feared. The Elizabethan stage was a bloodbath of feuding aristocrats, stabbing, drowning and eviscerating each other over the pettiest of squabbles. The public lapped it up.

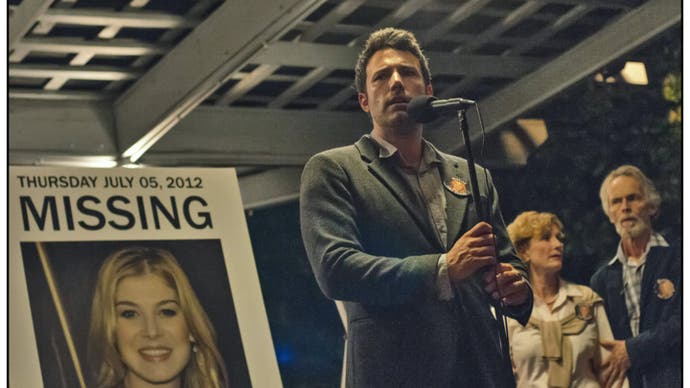

Right now, crime fiction is one of the most popular literary genres, with over 25 million novels sold in the UK every year. Most recently we've seen an explosion in the psychological thriller sub-genre, with titles like Gone Girl and Girl on the Train bringing in dark, twisting plots and incredibly graphic violence. Yet, for some reason, the sorts of people who would never play a violent video game will readily consume these tales filled with bloodied, mangled corpses and ruthless psychotic killers. Why is that?

Of course, the obvious answer is interactivity. A lot of people are okay with reading about the horror of crime, but perhaps they're less comfortable about enacting it. I'm not really sure I agree with this though. At a base level, games have become almost pervasive in modern society. Through smartphones, tablets, social networks and consoles that masquerade as set-top boxes and DVD players a huge number of people have become familiar and comfortable with the idea of interactive media.

At the same time, crime stories have historically been hugely playful and interactive. Novelists such as Agatha Christie, Dorothy L sayers and Margery Allingham - all considered part of the golden era of detective fiction - wrote stories that effectively worked as puzzles. The reader was challenged to guess the murderer before the narrative revelation, and most plot and subplot features were designed to either help or hinder that process. In Christie's books, the characters are almost utterly two-dimensional, acting as ciphers to the story threads that carry the player toward a deduction. Crime fiction is a game that people don't mind playing.

But there is a key difference in the way crime novels and games approach violence that alienates fans of the former from the latter.

What games often completely lack is an emotional framework for violence. In first-person shooters and action adventures, players kill indiscriminately to finish a level. There is no meaning or impact ascribed to any individual slaying. There is no milieu in which to understand the action, and therefore it's meaningless. Let's look at crime writers again. In the Sherlock Holmes stories, Conan Doyle was exploring the fears of the rising middle classes for whom conniving relatives, colleagues and professionals were more dangerous than madmen lurking in alleyways. In the modern noir stories of James Ellroy and Walter Mosley, we see murder as a symbol for the wider social tensions blooming in fifties Los Angeles; the ramifications of every bloated corpse dumped in a vacant lot extend outward to the whole community. In David Guterson's brilliant novel Snow Falling on Cedars a whole post-war community is torn apart when a murder is blamed on a Japanese immigrant. Every death has meaning.

It's a cliche that women don't tend to play as many violent games as men - but they sure read (and write) a lot of violent crime novels. Two of the biggest hits of the last few years, Gone Girl and Girl on the Train, are psychological thrillers about women, crime and violence that were hugely popular with female readers. Writing about this phenomenon last year, author Melanie McGrath, who says 80 per cent of the attendees at the crime writing festivals and workshops she attends are women, argued:

"Girls grow up inundated by messages about our vulnerability and learn to interpret the world through that lens. We're conscious of the statistics, alert to the long shadow, the unexpected turn of the door handle and the sound of boots on a lonely night-time street. In crime fiction we can explore those feelings safely. Resolving the crime helps resolve the feelings."

Authors like Val McDermid and Jessie Keane explore this sense of violence as a shadow looming over women, often via complex female protagonists (we saw a similar dynamic in the cult Scandinavian dramas The Killing and The Bridge). Meanwhile, in David Peace's Red Riding quartet the horror of the Yorkshire Ripper case ripples out from the murders themselves and darkens all the lives and relationships it touches. Yet in violent games, there are rarely emotional tangents or criminal consequences, so we don't get to experience this sense of vicarious horror and relief. Bloody acts of carnage exist in a vacuum of indifference.

In the past, crime games have tended to ape the plots and conventions of the literary genre - there have been excellent detective adventures like the Police Quest and Gabriel Knight titles that have provided the same whodunit intrigue of the golden age novels. There have been hardboiled thrillers like LA Noire, Deadly Premonition and Condemned Criminal Origins, that have understood the use of murder a a symbol for corrupt and degraded society. But they did little to create a tangible emotional connection with crime or its resolution.

This is changing. Both Heavy Rain and The Walking Dead provide players with moments in which they must weigh up the moral consequences of murder - and later they face the consequences of their actions. Although not a crime story, Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor places you in an environment where enemies remember you and bear grudges. More recently the underrated Until Dawn litters its "butterfly effect" mechanic with moral dilemmas where you must weigh up the needs and emotions of other characters against your own desire to "solve" the game - unlike Bioshock, this is ludology and narratology working in perfect partnership.

In crime fiction every corpse means something; the reader projects their own fears on to it, and the community within the story reflects and reacts to the lurking horror it represents. There is nobody in Uncharted or Tomb Raider to tell the heroes: you're a murderer. But perhaps there should be, because video games make us culpable in a universe that can change in an instant depending on our actions.

What can games learn from crime fiction? To put violence in context and make it mean something. To make it human. There's a reason Her Story was so successful, despite its limits as effectively a video footage search engine. Here is a real woman on screen and you have to slowly dislodge her story, not through hand-eye coordination or a quick trigger finger, but though the ostensibly laborious process of interpreting her confessions and understanding her as a person.

Of course there will always be room for military shooters, fantasy hack-n-slashers and gangland brawlers where bodycount is rewarded on a production line of death and XP. That's totally cool. But, we keep talking about the fact that this industry is at a crossroads where new audiences are sought and needed, and new experiences are desirable and possible. If games are really going to replace boxset television as the goto cultural medium - the place where we explore our hopes and fears as a society - then they will have to learn some more about violence.

When the theatre audiences of Ancient Greece saw the finale of Oedipus they recognised, in his blinding act of self-mutilation, all their fears about fate, free will, power and knowledge. That ages-old detective story still resonates with moral horror - and the same mood of grand hopelessness permeates the books of Jim Thompson, James Ellroy and Cormac McCarthy.

The great tragedians of violence and crime will one day be making video games - their gruesome tales of torture and remorse will put us, not in the stalls, but on the stage. Because, of course, somewhere deep down and not always clear, the solution to every whodunnit ever written is you.