Leanne Shapton's games of absence

"Estefania's ex-boyfriend suggested she wear darker jeans."

Drawings, paintings, photographs, found objects, and text: Leanne Shapton's work crosses boundaries. So what brings it all together? This: she is a poet of absence. Her best stuff often seems to speak of people who are no longer present, and the empty chairs she places on the stage are perfect spaces to allow the reader in. This is why, although I doubt anybody would call Shapton a game designer, her work always feels gamelike to me.

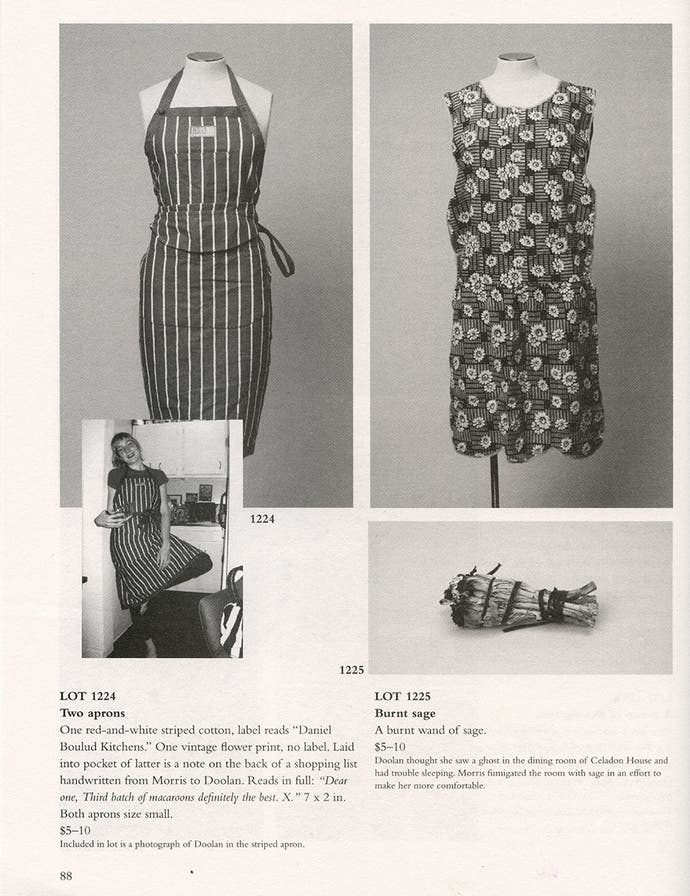

You can see this with something like Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion and Jewelry, which tells the story of a couple's relationship by means of an auction catalogue for all of their stuff. It's beautifully done: pages of chronological listings, from the flyer for the Halloween party at which they meet to a rather sad selection of old champagne corks - special moments no longer treasured.

It would be so easy for this book to be a conceit, a gimmick. But instead it is forensic yet, somehow, deeply tender. There is a role for the reader here in the absence of the main players - in fact, the role can be whatever you choose when making sense of things. I spent a lot of the book looking through the catalogue - swimwear, postcards, old paperbacks with notes in - and wondering if this is where the problems started, where these two unseen protagonists started to pull apart. It's a testament to how good Shapton is at selecting this stuff that the photographs of the couple themselves are the least convincing aspect of the whole project for me. They look like actors rather than the people who truly owned these objects and filled them with painful human meaning.

You can see this gamelike element in Was She Pretty?, too, which is a series of drawings and written snapshots revolving around people's exes, each one clearly viewed from the perspective of the present lover. "Estefania's ex-boyfriend suggested she wear darker jeans." "Lionel's ex-girlfriend Edie enjoyed Brahms. But she preferred money."

My favourite entry in this book is about a vase: "There was a vase in the dining room that didn't quite seem to Stuart's taste. Eugenie couldn't throw it away, so she hid it in a cabinet." The purposeful awkwardness of that first sentence with its tortured indirectness! Nobody is truly present here in these words, but you are tacitly encouraged to triangulate the bits of information that you have, to work out for the most part how the present lover feels about the former lover. We have all done this in real life, I suspect, which is another reason why it's such an easy role to slip into. That stupid, ugly vase!

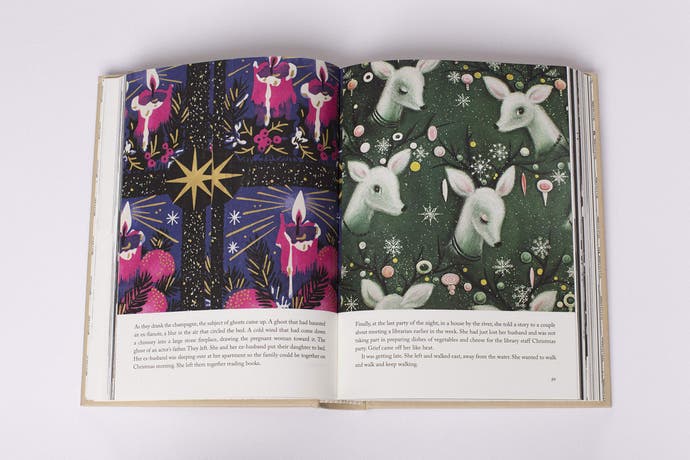

Anyway. My favourite of Shapton's books is also her most gamelike to me. Guestbook: Ghost Stories is a collection of - well, lots of things. There are floor plans, photo essays, watercolours based on old movies, even a section that looks like it's composed of Christmas wrapping paper. It's creepy and playful and sad. Quite a book.

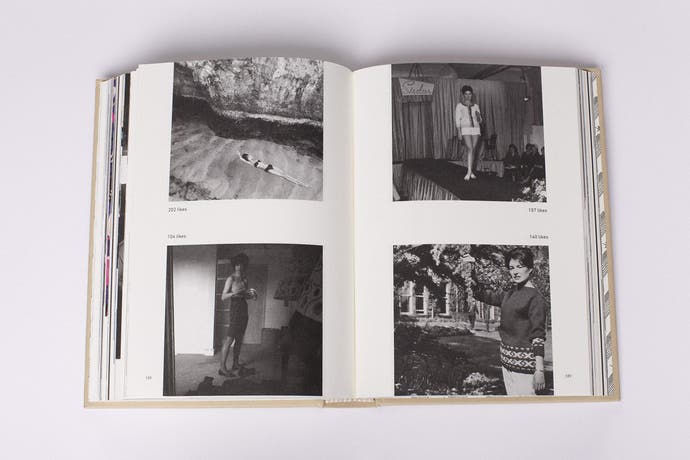

And weirdly, my favourite section is about a presence rather than an absence. In A Geist we see a series of photos taken at various society events - magazine launches, album listening parties, "Private dinner for Lucien Pak." The pictures are beautifully done - over-exposed or rendered Halloweenish by too strong a flash or background characters disappearing into living-room darkness. What's going on here?

The first thing that becomes clear is that one person is present in all the pictures - a delicate, rather elfen man in a sheeny blue suit. Here he is at a dinner party being playful with a wine glass. Here he is looking serious next to a lady with a fan. Here he is larking with a false mustache. The descriptions under each picture list him as Edward Mintz, which is a perfect name for a fellow like this. And then it clicks: all these events scattered across the world, all attended by Edward Mintz, are all taking place on the same night: November 2nd, 2018. This unghostly presence - a man who seems to fit in everywhere - cannot have truly been everywhere he seems to be, can he?

Otherwise, though, Guestbook too is defined by playful absences. A series of character snapshots appended to what appears to be found photographs may list the qualities of individual ghosts who haunt someone. Moody shots of house interiors - hallways and staircases and back rooms - are listed as being the setting for various moments in a dream that we are not fully told about. Onwards the invention piles up, new and more melancholy ideas, a lot being done with a little.

There are two games for me with this book. The first is simply to understand how each entry works, what the central idea, which shifts throughout the book, might be in this case. What are the rules? Where are the photographs or drawings from? What might have inspired Shapton in each case? (Shapton, inevitably, is one of the more looming absences in all her work.) Only then can you play the other game and work out how the ghost - or the idea of a ghost - relates to the story, where the absence, as it were, is actually located.

Ghosts are the perfect subject for Shapton, I think - ghosts of relationships, of lovers, of places and moments. Ghosts - and their games - can take many forms, too. One of my other favourite books of Shapton is called The Native Trees of Canada. It's a series of paintings of identifying leaves from various species of tree, and my sense is that a former book with this title exists beneath the paint of the book that Shapton has created. Beneath this colourful foliage the former book now lurks there, unseen, warm with its own meanings.