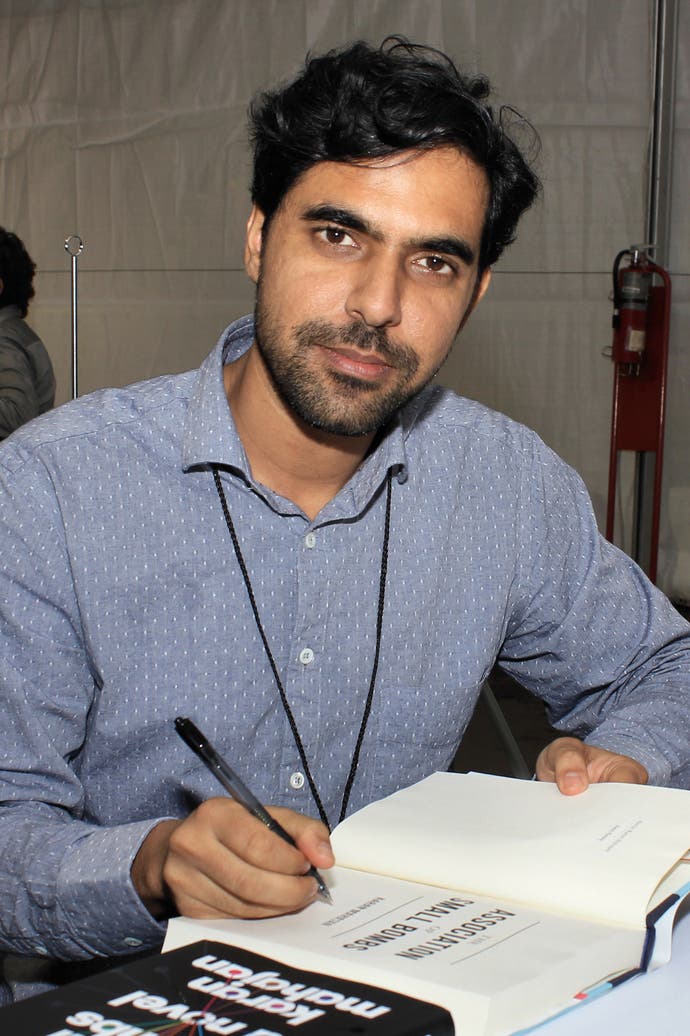

Letting your mind go in dense, dark worlds: an interview with author Karan Mahajan

Artefact of time.

A few years ago, I had some time to kill in Huddersfield and decided to check for any interesting books in the Oxfam shop. I'd never seen a copy of Granta before nor hunted one down, presuming my intelligence was below its target readership and assumed my pretentiousness lay elsewhere. (Spoiler: despite ongoing questions regarding my intelligence, it didn't.) But here it was, an issue dedicated to the best young American writers.

It included a short story by Karan Mahajan called The Anthology. I'd previously read his second novel, The Association of Small Bombs, and the queasy, uncertain feelings it gave me were reason enough to make me a fan. The Anthology brought out a similarly uneasy reaction in me, as it's another dark story, one about the aftermath of a bombing and it begins in Delhi in 2000 at a literary event. It's a world away from video games, but Mahajan's focus on politics and world-building felt relevant to the spaces where games often find themselves these days. Mahajan's work reminds me of Donna Tartt's theory of "density and speed" as being central to her work, something she emphasised during the release of The Goldfinch. "You're building a big, heavy article but you want it to go fast. You want the readers' experience of it to be fast. And you want there to be detail in it."

The Anthology is beautifully written, layering in humorous satirical critiques not just of the literary world, but also Indian society. The unreliable narrator - who we only know as the son of a Rajesh Soni, and nicknamed "Fatso" - relays the story of this fatal event, where literary elites gathered to hear an esteemed Kiwi writer. Unfortunately, with everyone else killed, a fellow writer named Ismail Baig emerges as the sole survivor. Soni, after agreeing with his friends that they should create an anthology of short stories inspired by this event, stumbles into Baig to ask for his blessing and to provide a foreword. It's wonderful to see how Mahajan almost pulls back the curtain to reveal why he focuses on such a dark topic, only for it to act as a decoy, as explained through the narrator: "Bombs always make the most of the slightest material... Bombs see the possibility in everything, and in this way they are like artists, brilliant improvisers, except that they happen to kill, and so isn't there a strange poetry, you ask, in a bomb that kills artists? No."

Mahajan spent the early parts of his life in India before returning to the US to study English and economics at Stanford, and is currently settled in Rhode Island. His first novel Family Planning follows Arjun, a young adolescent with twelve siblings who's having to deal with his politician-father and a crush on a girl at school. Mahajan is unlike any of the characters found in his chaotic, bustling worlds. He was calm, composed and charming during our video call over Skype.

I bring up the "Congratulations, you played yourself" meme courtesy of DJ Khaled, wondering whether Mahajan's conflicting American and Indian upbringing means he finds himself playing different characters in different environments. "I think I'm only unified as an individual and a character when I'm writing," he says. "That's the only time all these contradictory elements seem to flow together. Otherwise, yeah, I'm self-conscious at times in America, self-conscious at times in India, as someone who's from the place but now slowly aware of the growing distance between himself and the place."

To hear Mahajan speak about his books - which are far more politically charged than many video games - is to hear someone who sounds a bit like a game designer at the start of a new project: "I think this is the great thing about writing and why I do it," he tells me. "It's that I feel complete freedom. The only lack of freedom comes from the question of whether you're going to hurt people you know."

The fascinating thing about Mahajan's two novels is how they visualise the realistic, dense and hectic nature of Indian urbanism so well, despite focussing on a few main central characters and switching between them. I want to know how he creates these worlds, basing them in an India recognisable to many, but also very specific and detailed.

"I think it must be that thing that people say," he tells me, "which is experiences you have before you decide to become a writer have a kind of inchoate but also vivid presence in your mind. And how you see those experiences keeps changing with every year. Like you can return to the primal scenes of your childhood and you can see them through the lens of a 20-year-old, a 30-year-old, and so on. And they keep revealing vast storehouses of meaning and things that you hadn't at the time."

I wonder whether the true artistic freedom afforded in novels is something we're missing in video games. I would argue that only a handful of truly book-like games exist, such as What Remains of Edith Finch and the Life is Strange series, yet when we speak about this, Mahajan is respectfully bullish on the differences between these worlds. "I have a couple of writer friends who love video games," he says. "I think it's like TV, the place where the really major writing of our time is being done. Those are fulfilling the roles that novels used to fulfil fifty years ago."

I asked the unavoidable: about how the pandemic has affected his own writing, especially his inability to visit the cinema, something he's previously said is a useful source of creative inspiration. "I don't enter the same kind of dream space I enter when I'm actually in a cinema, sitting in my own house. I'm far more distracted, I'm looking at my phone. We don't think of it but we had such few sensory-deprivation places, and the cinema was one of them. So even if the movie was bad, you can kind of let your mind go."

Something that's been on my mind in the past year is how everything that's happened will be affecting different artistic work in unexpected ways, particularly as some people have used the time to explore new hobbies and interests. He left me with one last anecdote, about playing the Jackbox Party games during the pandemic. "It's funny because there's a kind of early multimedia quality to them. They're so lo-fi even though they use your phone. So I wonder if that, for people like me who are not big game players, whether that will remain as a kind of artefact of this period." For many people who've remained in one place for nearly a year and have done things (like this) that they may not have otherwise, it's going to be fascinating to see the type of art that's a result of this pandemic. With the hope and condition that death remains avoidable during the current awfulness, I can't wait.