Lie in my Heart and dealing with the aftermath

”You always wonder why all this happened?”

This article concerns a game about suicide.

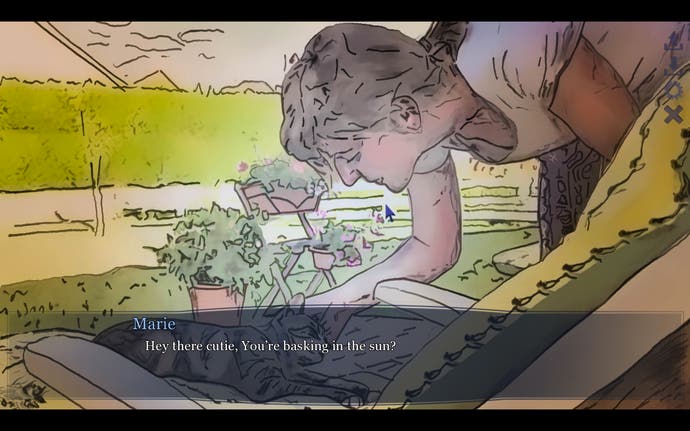

Lie in my Heart isn't really a game. OK, it is technically, but it's also the story of an awful time in one man's life. That man being the developer of the game, Sébastien Genvo.

A game developer as well as a professor at the University of Lorraine in France, Genvo made Lie in my Heart after his wife killed herself. Understandably, it was and remains devastating to him and the son he had with her. Yet through that pain and anguish, he chose to make a game to express his experiences and to highlight the confusion and agony that comes from a sudden death.

It's a tough game to play. I found tears came to my eyes very readily. Not least because after making a series of difficult decisions, from figuring out how to approach telling your son what happened to looking back at past memories, you're confronted with a note from the developer telling you how many of the choices you made strayed from his original decisions.

Essentially, that's a reminder that this really happened. At some point in the developer's life, they actually had to face these decisions for real. It's quite the gut punch.

After playing Lie in my Heart, I had to find out how on earth Genvo had the strength to make such a game.

"After this kind of tragedy, you always wonder why all this happened, what could have been done, was it really possible to avoid all this?" Genvo explains to me after I get in contact. "In my case, I also really needed to think about it to find the right answers to the questions of my five-year-old son."

While it's a personal story for him, Genvo also acknowledges that there are universal themes here: "losing a loved one, coping with mental illness, helping a child to deal with death." As he puts it, one of the purposes of art is, "to make us think about ourselves, about others, about the world surrounding us," while also moving and touching us.

Genvo previously earned a PhD in France for work studying video games, and was fascinated by how games can engage people of different cultures, taking different meanings and forms depending on how players looked at them. He was keen to explore the concept of 'expressive games' in which "players [are given] the opportunity to take someone's place in order to explore personal psychological and social issues, as well as moral and ethical dilemmas and their consequences."

Citing paediatric psychiatrist D. W. Winnicott who said that "games are an intermediary space between reality and fiction," Genvo explains that he wanted to make people think about themselves as well as others.

After all, as he points out, there's a lack of autobiographical or biographical games compared to other mediums. Which is a bit weird when you think about it, isn't it? The ones that do exist are indie games such as That Dragon Cancer or Cibele, both used as a form of catharsis by the developer. That's clearly evident with Lie in my Heart too. We all talk so much about how games can help us get through hard times, yet seemingly few games actually reflect those hard times.

Genvo points out that Lie in my Heart is both "a representation" of what happened to him, yet also offers fictional paths for the player to explore. There's that constant need to offer playability and balance, as well as tell the story that the developer wants to tell - a stark contrast from the reality of a filmmaker who can pursue their vision and stick with it until the conclusion.

The different paths created by Genvo are fascinating. While playing, you'll find yourself instinctively leaning in certain directions, then questioning whether you should have gone that way. Traumatic events are exceptionally tough to wrap your head around even when given the time to think answers through. "Some paths are things that could have been, others are inspired by hesitations I had while facing the events and some are there to allow the players to recognise themselves in the events," explains Genvo.

It's natural after any trauma to question what you could or should have done if you'd had time to think, and Genvo captures this so well here. While not necessarily healthy in the long term, it's natural to think, think more, and overthink what a simple change to one answer could have led to. Ultimately, in Lie in my Heart, you can't 'save' the character's wife. Life is too complex for easy solutions and that's reflected here.

While it seemed to me that Lie in my Heart was a form of catharsis or therapy for Genvo, he disagrees. "It was first and foremost...an act of creation based on my life. I did not want to do that to feel better or to find a cure in the process," he says, suggesting there are other ways for him to do that. Instead, "it was often difficult to think back about all that happened, remembering things I tried to put in the past to move on with my life," he explains. Genvo hopes that it will be an important game for other people rather than for himself.

In the game, you don't spend a huge amount of time getting to know Théo, Genvo's son, but I was pleased to learn that he's doing well. Théo's favourite games involve playing as a pirate and playing with trains - two things linked to his mother - as you'll learn courtesy of Lie in my Heart.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org.