Lifeless Planet: Encounters at the end of the world

How one Alaska-based developer is making the year's most interesting sci-fi game.

Before David Board moved to Alaska, he had never seen a really big pumpkin.

"People forget that in the summertime we get ridiculously long hours of Arctic daylight up here," he tells me over a surprisingly clear Skype connection. "The sun does set, but it's still bright enough for you to go outside and read. We have the state fair here in Palmer where I live, and they have record-breaking vegetables. I'm not kidding. 1000 pound cabbages, two ton pumpkins. Those pumpkins, they're bigger than my car. Literally bigger. It looks like a joke out of a kid's storybook. And it's not just one or two big pumpkins - everybody's got them."

Given the size of the produce alone - and given the remoteness, the ruggedness, the strange, stark prettiness of Alaska - it's no surprise that when Board catches up with friends from the lower 48, they all wanted to understand the same thing: what's it like to live there? "Before I moved up here, a friend said, 'Where are you going to shop?'" he laughs. "I said, 'Oh, Wal-Mart, Sam's Club.' She said, 'Yeah, right,' and I said, 'What do you mean? I'm serious, we have all these big box stores, the regular restaurants.' If you didn't look around and see mountains, you'd think you were in Kansas."

In truth, Board argues, Alaska's a blend of the mundane and the alien. The very combination can be jarring at times. You walk out of a Starbucks and see a glacier on the horizon. You go for an afternoon drive and those giant two ton pumpkins are waiting by the roadside. It's not hard to see the appeal of a place that Board describes as being "wild and cool and crazy", and it makes sense hearing all of these odd Alaskan experiences in the light of Lifeless Planet, the designer's debut video game. Lifeless Planet's recently hit Steam Early Access, and it's concerned with the same surreal intersection of the familiar and the fantastical that Alaksa delivers. It's about taking a trip to a very far off place, and finding more - and, teasingly, less - than you expected.

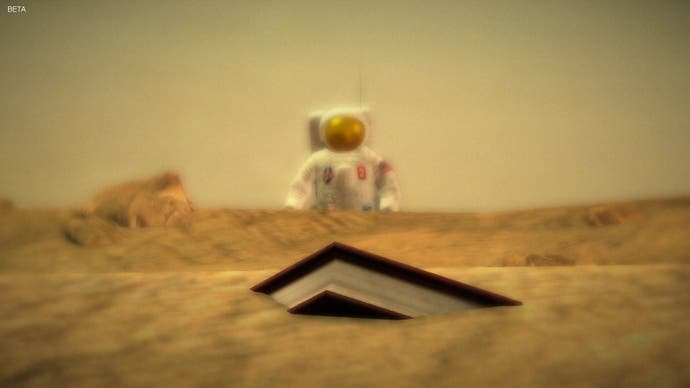

Board's action-adventure casts players as an astronaut who's accepted a mission to a distant world that looks promising in terms of its atmosphere and vegetation. It's a one-way trip, and a good deal of the melancholy mystery of the early part of the game comes from pondering why anybody would sign up for such a job in the first place.

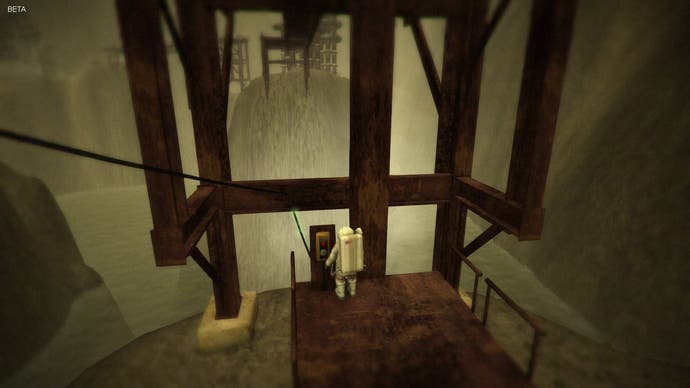

The rest of the mystery's handled by what happens after the astronaut lands - and once the gentle platforming and physics puzzles have started to draw you into their easy-going rhythm. This planet which was meant to be rich in basic life turns out to be a barren dust bowl: craggy rocks, huge, gaping ravines, and endless expanses of desert and rubble. What happened? Where are you going to shop? Exploring a little, an even greater puzzle suggests itself. Rounding a hill, the astronaut finds a set of telegraph poles leading starkly into the distance. There's a deserted soviet factory town here, and signs of an aborted attempt to settle the planet in the name of Communism. How did the Russians manage to get all this way into space back in the 1980s? And where did they then disappear to?

Although Lifeless Planet is Board's first released game, he's been tinkering with design for years. He got his start as a teenage coder with a VIC-20, before migrating to the Atari ST and finally the PC. His parents' house is still filled with notes and sketches he created as a young boy, dreaming big. He made a Counter-Strike map that once made it onto a PC Gamer cover disk - it was called de_museum, if anybody remembers it - and he now spends most of his time as a partner in a small media production studio that specialises in making video, TV and interactives for non-profit organisations and charities. "I'm also very interested in science education and that sort of thing," he says. "I think by default that makes me a sci-fi fan."

On hearing this, it's hard to shake the feeling that Lifeless Planet is a portrait of its creator: it's a gentle, earnest, rather deep-thinking sort of game, and its take on science fiction, despite its brilliant and outlandish Soviet hook, puts a careful premium on plausibility. ET: The Extra-Terrestrial once managed to make the iconic US astronaut spacesuit monolithic and terrifying; Lifeless Planet uses it as an intriguing symbol of fragility, of the tenuous position mankind occupies in the universe. Explorers are made of glass here: fall damage is dialled up and your oxygen is constantly running down. In dark sections of the game, your torch fails to penetrate very far into the gloom, while, even when kitted out to allow for multiple bursts, the on-board jetpack only launches you a little way into the air.

If Lifeless Planet is a reflection of its lone designer, I suspect it's also the kind of game only a lone designer could have made in the first place, too. It's scrappy but smartly focused. It's sparse and quietly obsessional. Is that a product of working alone?

"It partly is," laughs Board, "but I'll also let you in on a secret. One of the things I thought when I was going into this - I knew it would be a huge undertaking, but even so the project started small and I wanted to keep it small. I created a 60 page design document and I wanted to make sure I had everything covered. I knew that with scope creep and producing all this myself, there would be a lot of pitfalls. But the secret is, one of the first design decisions I made was: this cannot be a Far Cry 3. This has got to be a place that, while its beautiful, has to be beautiful in stark and somehow barren ways."

This decision influenced every aspect of the game, from the dead landscape at the heart of the narrative to the way progression favours simple puzzles and exploration over any kind of combat - a welcome decision that more story-led games could learn from. "It could have been a limitation," says Board, "but one of the things I've found about art and design over the years is that very often, limited decisions, from a client or the scope of the project like this, or the software and tools you have available or the time limit, sometimes those things can lead to really spectacularly cool solutions. That's one of the reasons I like design so much as opposed to just raw art. There are so many limitations. It becomes almost a logic puzzle mashed up with art. Some of the best planned projects don't work fantastically.The unexpected ones are the fun ones that just grow organically." Organically around a 60 page design doc? Board laughs. "This was definitely a combination of planning and luck."

Throughout the current beta demo, which takes about two hours to reach its cliffhanger ending (and which represents about a third of the final game), Lifeless Planet does a lot with a little. There are some wonderful set-pieces as the astronaut probes deeper into the bizarre landscape, and they're all the more effective for being composed of such simple pieces. Powering up a dormant underground science laboratory in one sequence not only turns the lights on, for example, it also sets the old Soviet national anthem playing - rousing patriotic pomp warbling over a scene of abject dereliction and failure to create a moment that's as neat, as sharp and as ironic as anything in BioShock's Rapture. Even better, the game's narrative unfolds as a procession of lingering images - those telephone poles marching into the dust clouds of an alien world, the sharp lines where cheap concrete and rebar meets ancient stone. I ask Board if this is how the game came to him - in the form of a series of pictures, jarring despite their straightforward elements, all of which hold more questions than answers.

"Absolutely," he replies. "I see game design in terms of the way I map out my levels. In a pure open world game you can do this a little bit, perhaps, but I have the benefit of a more linear story. There's always a destination, there's always a place to go. I see the level design as setting up these visuals, and I will spend hours staging a moment so that the geometry of a level reveals a view in just the right way. The point is that you go from one visually striking moment to the next. And here's the thing of it - I love playing games that do that for me. I think back on games like Ico or Out of this World where you just want to get through that level to see what's next. That's what I'm trying to achieve here."

That said, Board still seems to want to make things hard for himself. What's most immediately unsettling about Lifeless Planet isn't the narrative that's unfolding, but the space it unfolds in - or rather, the careful illusion of space. Board's levels feel boundless even when you're being very tightly controlled: he's astonishingly good at directing the eye and subtly cueing you in to the path ahead, sometimes with nothing more sophisticated than a scattering of pebbles.

"That was very important to me," he tells me. "One of the things I thought about this game early on was, it's this lifeless, barren planet? Oh my gosh, that could be the most boring thing ever produced. So what I did was two things - one was to create a sense of flow that doesn't feel forced. It's true, it's a story-driven game so I'm trying to take players through certain areas in a certain way, but I don't want players to feel, 'oh, I had to go that way. I'm on rails.' And yet I had to do that and at the same time create this sense that, my gosh, this is a huge place and the distance rolls off in every direction."

With development drawing to a close - an actual release date for the full game should be announced "very soon" - Board's gotten pretty comfortable talking to the press about Lifeless Planet. An issue that keeps coming up whenever he speaks with the Russian games media, however, is whether or not the Soviets will turn out to be the bad guys. "And I tell them without spoiling anything in the story: No." He laughs. "To me the Russians in the story are kind of stand-ins for humanity. It could have been anybody."

In fact, as we reach the end of our conversation, Board admits the Russians weren't even Russians initially. "At first I just had the image of the abandoned town out there. I brought the Soviet stuff in because if somebody in Russia made this game it might be a nuclear testing site in Arizona or something. I'm just writing from my perspective, and growing up in the 1980s, that was an extremely intriguing time with the Cold War and everything. Tie that into the history of the space race and everything? it just seemed to fit."

Ultimately, Board suggests, Lifeless Planet's more concerned with humanity itself rather than specific ideologies. What matters is the fragility of that spacesuit, not the politics of the man inside it. "It's sort of silly to think we'll ever travel to and explore a distant planet," he says wistfully. "I'm sceptical even in a 100,000 years if that would be possible."

He chortles to himself. "Then again, I always like to say: Well what about a million years? It's impossible to guess at the future, but still that's how we think. We still believe we'll do it some day. It's a ridiculous notion and yet it's how we approach the world. The whole story of this game is sort of expressing the vastness and the hugeness and the unknowableness of the universe and how truly tiny we are within it. But then the key for me is to take that down to the human level - to find a way to bring that idea home."