Lord Dunsany's chess variant is grim and kind of brilliant

"Damaging characteristics."

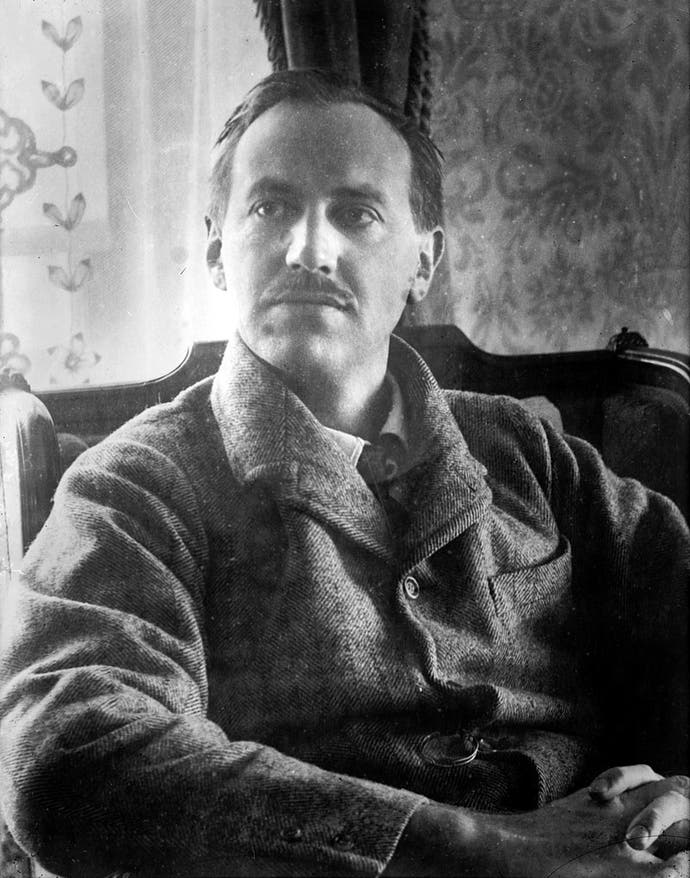

I first read about Lord Dunsany - I am happy to report his full name was Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett - in a collection of Arthur C. Clarke's non-fiction. In an early essay, Clarke describes going to see Dunsany, a beloved fantasy and science fiction author, when Clarke was young and Dunsany, who was born in 1878, was already getting on a bit. There is a moment in this essay that has stuck with me.

Clarke is getting one of his books signed. "I took with me a copy of his fantasy The Charwoman's Shadow...which he duly autographed with a sweeping DUNSANY running right across the page; it was the only time I ever saw anyone use a quill pen and then sprinkle the result with fine sand to dry the ink." That is wonderful, but re-reading the piece this morning I am delighted to see that Dunsany also corrected a mistake in the text. "'The Country Towards Moon's Rising' was transformed into 'The Country Beyond Moon's Rising.'"

I tried to get into Dunsany shortly after reading that. His books were hard to come by at the time and the only printings I could find were cheap and unpleasant - if Dunsany had tried to sign these, his autograph would have bled through from the first page to the last. But also this: Dunsany is a writer of serious whimsy - more on this in a bit - and serious whimsy is something you have to be in a certain mood to enjoy.

So I bounced off Dunsany and went back into orbit, and circled the Country Towards/Beyond Moon's Rising for the best part of two decades. He became the sort of writer I loved to think about - a mysterious link in the gnarled chain of fantasy. The sort of writer I would ask other writers about when I met them.

Then I encountered Dunsany again in Christopher Fowler's glorious collection The Book of Forgotten Authors. I urge you to buy this wonderful, generous, endlessly discursive book. If nothing else it's the perfect present for problem birthdays and Christmases.

Dunsany gets two pages here, which may not sound like much, but with Fowler it's enough to get a full measure of the man. Dunsany, I read, was 6 foot 4 and a cricketer, chess champion, and he lived in Ireland's longest-inhabited dwelling, Dunsany Castle. He wrote whimsy, yes, but again: serious whimsy, the detailing was bright and "his wonder-worlds are remarkably well-realised, and populated by elves, fairies, trolls, gods and various immortals who, although clearly supernatural, possess the damaging characteristics of humans."

Damaging characteristics! I love that, and I love the fact that in the sweep of fantasy, Fowler locates Dunsany with precision, "between Richard Dadd and the Moomins."

I returned to Dunsany after that and got another cheap paperback - Dunsany's Wonder Tales. I read "How Nuth Would Have Practiced his Art upon the Gnoles," which Fowler recommends - a story of professional thieves and unmentionable punishments. But again I bounced off. And I couldn't say why. Dunsany grabbed me as a character himself, but I couldn't really bring his work to life.

Maybe this will change. Last week, for whatever reason, I was looking through a list of chess variants and I came across Dunsany's Chess. Not Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, surely? Then I remembered that bit in Fowler about Dunsany being a chess champion. Then I took a look at the variant, and there was no doubt that this belonged between Richard Dadd and the Moomins. It's whimsical, but it's serious. And it's sinister AF. Was this, finally, a way in?

Dunsany came up with his variant in 1942, and there is something of wartime to it. It's an asymmetrical spin on chess (yes, I appreciate that with White going first, chess is already asymmetrical) and it's very striking, even, I imagine, if you don't play the game.

In Dunsany's chess, Black has all the normal pieces in all the normal places. But White has 32 pawns, arranged in four lines. Black moves first. Only Black's pawns have the two-step option on their first move. White wins by checkmating Black, but Black wins by removing all 32 pawns.

Even before I sat down to play this myself: cor. What a brilliantly horrible set-up. I tend to think of chess as airy and elegant, a game with nice grown-up fonts and a lot of white space on the page. But here it's something else. It's chittering and scrabbling, order versus a kind of chaos. The pawns cease to be whatever it was that I had assumed pawns were and become a kind of endlessly rolling mass of grim alien tissue. It's The Flood from Halo. No wonder a similar variant is called Horde Chess.

Listen though. Reader: I have now played Dunsany's chess. Several games, as Black and White. Cripes. It is a monster.

I started as Black, which I thought would give me the edge of familiarity. But even before you've moved it's wretched. You're not looking across at your noble opposites anymore, no more battlefield as mirror. Instead, it's just endless pawns, and they're stacked so close you can almost touch them. I made a few moves, took a few pawns, and realised that I was making no inroads at all. Every pawn I took just allowed another to ooze forward into its place. It was like being stalked by a small ocean.

About halfway through my first game as Black I gave in to panic. Total panic. I started throwing my own pieces away for a reason I didn't really understand myself. I just felt like I had to do something to be out of this grim, oppressive game. Knights and bishops, my queen, even my beloved rooks all went into the waves. It was a relief when I was checkmated simply because I didn't have to think of the sheer asymmetry of it anymore.

Playing as White was, somehow, even worse. I imagine it's a bit like maneuvering a delivery lorry after learning to drive in an Isetta. I simply had no idea how big I was anymore. My pieces didn't feel like pieces, but the tendrils and frills of a single, hideous entity. I kept bumping into myself, blocking myself, getting bits of myself stuck on the scenery.

I am a bad but enthusiastic chess player. I love a game. But I have never played games as wild and disturbing as these. I could probably go online and read about the history of Dunsany's chess, but I really don't want to anymore. The story seems pretty straightforward: I suspect Dunsany was not entirely happy about things when he created this game. There is fear here and horror. There is something of the endless sacrifice of 20th century warfare to it, but also something alien and depraved that must lurk deep in his fiction? I played Dunsany's chess to get an inroad into his books, and now I'm not sure I want them in the room where I sleep.

And more. I keep coming back to that visit with Clarke and Dunsany, the autographing, the quill. And the sand. Sprinkling sand so the ink does not spread - across the page, across the table, advancing forever across the tiled floors of Dunsany Castle and out into the green and blue world beyond.