Lost Odyssey

Get Lost. In a good way.

Given the involvement of hotshot RPG superstars like Final Fantasy creators Hironobu Sakaguchi and Nobuo Uematsu, it should come as no surprise that Lost Odyssey is utterly, utterly traditional. There's no fannying around with real-time combat here, like there was in Final Fantasy XII, just reams and reams of random battles, exploration and cut-scenes. Over the course of its 40-odd hours, it progresses at a glacial pace, taking a good few hours after you fire it up just to reach the barest semblance of a plot (which, just so you know, involves an immortal called Kaim trying to discover why he's been alive for so long).

In this, it is identical to every single other Japanese RPG to have ever existed. Indeed, there is little here to address the many failings of the form. Characters enter battle with earnest catchphrases like 'only the strong survive', and leave it only after punching the air to celebrate success. Battles are random - very random: playing through one stretch of the game twice triggered about seven encounters the second time after precisely none the first time. You'll spend at least half of the game searching through bins and rifling through strangers' drawers while they watch you without caring. The hero is - and I've forgotten how many times we've seen this before - an amnesiac. And the story, which is spread across four discs, frequently veers into saccharine sentimentality.

There are the inevitable stealth bits, treasure hunts, and item auctions, assembled into what could only be called bite-size chunks if you have a planet-sized mouth. Don't even think about sitting down to play Lost Odyssey if you haven't got an entire hour to play it: most save-points are between 20 and 40 minutes away from each other, and many of them are nearly an hour apart. Then there are moments of utter absurdity, like the bit where a queen flashes her chest at some armoured guards to secure safe passage to a foreign king, or the bit where you're forced to play through a series of funeral-based mini-games. Technically, it's all over the place, with neat tricks like depth-of-field effects offset by minor glitches like a smattering of eye-hurting frame-rate stutters. Even for what is a resolutely traditional Japanese RPG, cut-scenes are noticeably long, and there are lots of them.

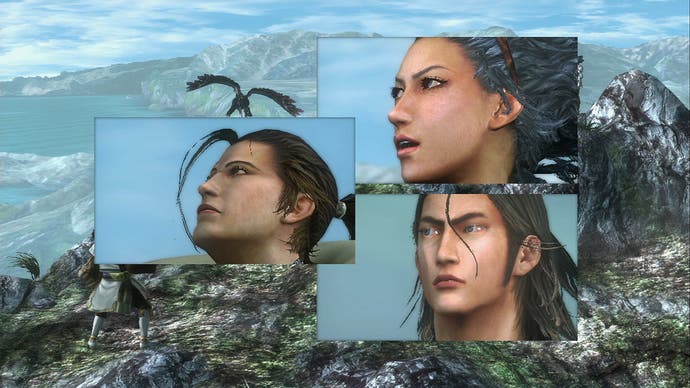

Yet, for every head-scratchingly bonkers bit, there is an equally astonishing eye-catchingly awesome bit, like a sky full of flying ice shards, dealing all sorts of cold-based destruction, or the bits where various gargantua stomp around laying waste to cities. And the cut-scenes may be long, but in general the story they tell is a decent one, and they're jazzed up by the extensive use of 24-style image-in-image and split-screen editing techniques. The dialogue is respectable, and it's backed up by voice-acting that's generally good, with Kaim's immortal ennui encapsulated in a monosyllabic Keanu-Reeves-in-Point-Break monotone.

You can even forgive the problematically spaced save-points, because you'll be spending mountains of time playing Lost Odyssey anyway; in spite of all of its ups and downs and traditional failings, it's very difficult to turn the game off. Just when you think your patience is wearing thin it'll reel you in with another teasing narrative thread, or ensnare you with another new skill or item, or it'll throw a new game mechanic for you to play with.

Given the involvement of Mistwalker's hotshot superstars, it should come as no surprise to find that it's superbly polished. Its production values are universally high. The main musical theme, for example, treads the same doleful ground as Michael Galasso's soundtrack to In the Mood for Love. The character design and environments are superb. And over the course of the game, Kaim uncovers various 'dreams', or short stories, that are written by award-winning Japanese novelist Kiyoshi Shigematsu, and translated by Jay Rubin, a Harvard professor who is better known for his translations of Haruki Murakami.