Making Cyberpunk: when Mike Pondsmith met CD Projekt Red

"This is pretty posh for a bunch of guys working in a broom closet."

"We had Communism and we had Cyberpunk."

Mike Pondsmith would hear those words 25 years after he'd joked about how few people would play a Polish translation of his American paper role-playing game Cyberpunk in a country behind the Iron Curtain. They would be the words spoken by a company offering him the deal of his life, and the words responsible for him signing it. Now nearly 30 years after Mike Pondsmith first published Cyberpunk, we're about to see the fruits of the seeds he once inadvertently sowed: Cyberpunk 2077.

With The Witcher series resting in the wings, CD Projekt Red is ready to bring this new collaboration centre stage, and as the spotlight of attention on Cyberpunk 2077 swivels closer, Mike Pondsmith is naturally caught in the glare. Who is this man behind the game CD Projekt Red's near future will be based on - and how is he helping shape it? I followed Mike Pondsmith to Spanish conference Gamelab to find out.

Face to face, Mike Pondsmith is a storyteller. You've seen him before in a video promoting Cyberpunk 2077, but he's embarrassed by it. It was four years ago and he isn't anywhere near as moody in real life. If anything he's sassy, relishing in a story's build up before dropping his head and looking over his pencil-narrow specs for the punchline. He's easy company and seems to know everything, as game designers do. "You need to read everything; you will use everything," he says. "You eat mozzarella, you eat dough, you eat tomatoes and you spit out pizza." He's got a million silly sayings like that.

He grew up a "service brat", always moving home with his US Air Force dad, spending time living in Germany as well as all round the States. It gave him an eclectic perspective, a never-ending string of teachers and influences, and who knows? Perhaps not a regular crowd of friends to entertain himself with. By 11 he'd discovered science fiction, and by 11 he'd also made his first game: a chess-like creation played on a rectangular board with raised squares representing different stages of hyperspace. The idea was to get your ships to the other side, dodging the enemy ships by dropping in and out of hyperspace.

He tells a memorable tale about his first run-ins with Dungeons & Dragons. "This was way the heck back," he begins. "One of the guys in our circle brought back a copy of the original Dungeons & Dragons and came back and we made characters and played, up all night. And we were loud with it.

"[My friend's] apartment was down in a fairly seedy part of Berkeley, and one of the nights we were making so much noise that one of the ladies of the evening actually came by to find out what we were doing and... she got into it! So we had this woman who, when she wasn't turning tricks, was basically playing our cleric."

He was into sci-fi, comics and war gaming but also played in bands. "I wasn't exactly a geek," he says, "because there weren't geeks then," and by university he was even positively "obnoxious", as his future wife would once describe him - he'd asked her friend out instead of her. "That was during my weird 'big man on campus days'," he explains, "when I was dating a lot of people and being, 'Hey, here I am!'"

To get another shot he'd have to pick up gaming again and join an Advanced Dungeons & Dragons group she was in. "And I got invited into a game that was currently being run by her old boyfriend," he says, "who proceeded to try, in every way possible, to kill my character!

"You've gotta understand, back then I had a big afro, I wore mirrorshades, a ratty army jacket, motorcycle boots and carried a six-inch knife - I'd been working in West Oakland which is a real rough neighbourhood. I did not look like the person you wanted to bother! And so there I am in his game and we'd all be on the wall somewhere, fighting some orcs, and he'd send a balrog after me."

But the balrog didn't work - do they ever? - and Mike and Lisa are now living happily ever after. But more importantly back then, Pondsmith was back in gaming, and back in gaming shops, where one afternoon he bumped into Traveller, a science fiction role-playing game. "I was stoked," he says. "I got it back and I whipped out my black books and I started working."

He was around 20 years old when he made what would become his first commercial game, Mekton, inspired by Japanese comic Mobile Suit Gundam. A game about big robots fighting each other. He used the type-setting machine at the University of California, where he was working, to make it, then took Mekton to a conference nearby to try it out. Six people played the first day but 40 people turned up the next, and they wanted to know when they could buy it. Pondsmith borrowed $500 from his mum in 1982 to start R. Talsorian Games and fulfil their wishes. "I was now a game designer whether I planned to be one or not."

The idea of Cyberpunk came to Pondsmith while crossing the San Francisco Bay Bridge at two o'clock in the morning roughly five years later. Blade Runner was his favourite film and he really loved how the city looked that night. "Hmm I wonder..." he thought.

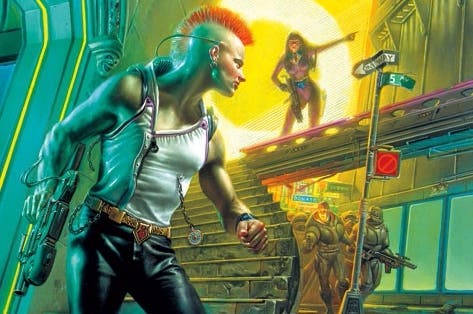

He wanted to create a future - the first edition was set in 2013, jarringly - where society didn't work but access to technology and information allowed normal people to overcome the barriers and restrictions usually held in place by a powerful and influential elite. "And that access," he says, "is rebellious, it's dangerous, it takes risks."

Cyberpunk was the 1980s: the bottled excitement of where all the rapidly evolving technology - mobile phones and personal computers! - would lead, mixed with a blaring screech of punky nonconformity. A game of "big guns, rock and roll, drugs and craziness". "All the bad things you're supposed to not do in other role-playing games - not supposed to rob, not supposed to steal, not supposed to bust into buildings and say, 'Give me your cyberware and all your chips!' - you do that in Cyberpunk." He would give people "a wonderful opportunity to do bad things".

"I figured it would do well," he says, "but I didn't expect I would be riding a cultural wave. It sold just ridiculously. It was a life-changing release."

The success of Cyberpunk, released in 1988, moved R. Talsorian Games out of Pondsmith's house and into a proper office, and would dominate the company's output for years, producing numerous supplements as well as a second edition, Cyberpunk 2020, in 1990. A third edition would have arrived earlier than 2005, but was delayed when Pondsmith's self-described knack of predicting the future threw up a problem.

"I blew up the Arasaka twin towers in Night City with a nuclear weapon," he says. "I'd written it. I was sitting there, finishing off, doing a sequence where a full-body cyborg is running around - she's basically part of the recovery team getting bodies out of these gigantic buildings that have been blown up. I finish this, I walk out, and I look at the TV and I go: 'Is that a movie or something?'"

It was September 11th, 2001.

"This is too chilling," he thinks. "I'm watching the World Trade Center going, 'Not only am I horrified about this but I've just done this entire sequence, including the fire and rescue people going in, pulling people out of the building, the wreckage. I'm going, 'Oh no, no no - this is just ridiculous.' This is why Cyberpunk third was late."

But no amount of success and forecasting could keep the paper gaming market from crashing and burning in the late '90s, and Pondsmith, now with dozens and dozens of releases under his belt - including new series Castle Falkenstein - was forced to put Talsorian on ice and look for another job. "I had a kid to raise," he says.

Then the phone rang. "And Microsoft showed up out of leftfield and said, 'Hey you want a job?' And I went, 'I already have a job - I have a whole company.' And they went, 'Oh you can keep your company, that's fine.' And I went, 'Okay... How much are you paying me?' And they gave me a number and I went, 'That's more money than God.'"

His Microsoft job was running a concept team, coming up with ideas for big teams to move onto when their projects wrapped. He worked on games like Crimson Skies, Blood Wake (an Xbox launch title) and the Flight Sim series, and "oversaw a bunch of other teams that did things that never made the light of day". Microsoft even sent him to pitch a Matrix game idea to the Wachowskis, but despite bonding over a love of kung fu/wushu, and enjoying each other's company, he didn't get the gig.

He would go on to work on The Matrix Online at Monolith, though, "a very odd project I never quite figured out what was going on with, except that the directions kept changing". By the time The Matrix Online came out and sunk, Pondsmith was freelance and eyeing a teaching post at DigiPen Institute of Technolog in Redmond, Washington - and The Matrix Online remained, for a long time, the closest he came to making a Cyberpunk video game.

Then in 2012, in the midst of an R. Talsorian Games reformation, the phone rang again. It was a call from Poland, from The Witcher studio CD Projekt Red. "CDPR drop out of the sky and say, 'Hello we're a bunch of guys from Poland and we want to do Cyberpunk.'

"We're cracking up," he says. "When we did the licence my comment was, 'Well there will be six guys who play it in Polish,' and it turned out they were the people who did!"

He was sent The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings as a kind of convincer and, "holy crap", he thought it was great. But he was also sceptical. It wasn't the first time someone had asked to do a Cyberpunk video game. "It's been pretty much under licence since its inception," he says, and several major publishers had had a shot. The closest it came was contract negotiations "but the problem was they wanted to change almost everything involved" and so the negotiations fell apart.

He'd also seen Eastern European development studios during his several years at Microsoft, where he also worked as a studio sorter-outer - a fixer. "I had been to a lot of countries that had just come out from the Iron Curtain and worked with dev houses over there, so I figured CDPR was a bunch of guys in a little sweatshop somewhere," he says. "In one place in Hungary they produced beautiful stuff but it was literally a broom closet with 25 guys crammed over overheated monitors. That's what I expected."

Yet, intrigued, he took the offer of a trip to Poland - and his mind began to change. "I get over there and they set me up in this really nice hotel and give me this driver who looks like he should have been driving spies around. He was almost as wide as he was tall, had heavy accent like ziss, spoke very little English, wore a severe black suit and drove a Mercedes.

"'This is pretty posh for a bunch of guys working in a broom closet,'" he thought - but he was still preparing to let CD Projekt Red down. It wasn't until he got into the studio and cast his Microsoft-trained eye over tools, procedures and general set-up that he thought, "Wow. This works."

What impressed him most, however, was how much CD Projekt Red knew about Cyberpunk. "They knew more about a lot of the things we did in the original Cyberpunk game than anybody we'd ever talked to," he says. "There were points where I was going, 'I had forgotten that,' and I wrote the damn thing! I realised these guys are fans. They loved it because they had grown up playing it. Nobody had really looked at it from that standpoint before."

CD Projekt Red shrugged and explained: "We had Communism and we had Cyberpunk."

"And that," Pondsmith says, "sealed it for us."

When he struck his deal with CD Projekt Red, Mike Pondsmith had many advantages over the studio's other major licence partner Witcher author Andrzej Sapkowski, who openly bemoans his lot. Sapkowski had no faith in games and no faith CD Projekt Red would actually make one. A decade later, Pondsmith - who had plenty of faith in games already - could play The Witcher 2 and see development of The Witcher 3. He had also spent time working on intellectual property at Microsoft so he knew what kind of deal he wanted to cut. "Suffice to say we made a lot more money in this deal than Sapkowski," he tells me. "I don't want to retire but I could."

The deal took around six months to strike. "It was a longer process because we were thinking in terms of a series and a franchise," he says, "so we had to figure out 'how is this going to work five games from now?'"

The deal declares CD Projekt Red the rights to "Cyberpunk 2077-backed stuff until the end of time and hell freezes over" - and exclusively, from what I can tell. "The way we operate is we do everything up to the 2077 period and they do beyond. Part of that was to allow everyone a little room.

"When I write new stuff for Cyberpunk now, I talk to them so what I do in 2030 matches up with what's going to happen in 2077. It allows them the ability to move forward and I can still create new stuff as long as we stay coordinated."

For instance: "A couple of weeks ago I went over the current story script and was going through it, 'okay okay this is great this is great - oh by the way that person is dead'," he says. "We're constantly going back and forth, we work really hard on the timeline. We want people to have that sense that there's a coherent universe. They mesh together surprisingly well."

CD Projekt Red didn't realise Pondsmith had a decade in video games until a few meetings in. "That's when the deal shifted from being an IP deal to my being actually pretty involved," he says, and the collaboration began with getting the Cyberpunk feel and concepts in place.

"Most people tend to look at it as 'if it's grim it's Cyberpunk'," he says. "I really believe that there should be something that's kick out the jams, rocking it, raising hell - the rebellion part of it. That's what we've been aiming for, to get that feeling. I want people to feel like it's a dark future but there are points you can have fun in it."

Cyberpunk also has to be personal. "You don't save the world, you save yourself," he says. "That's a very important thing. You're usually not the hero, you're absolutely downtrodden, you're usually the people who are not going to be up top but access to technology, knowledge, and 'what the hell I'm going to do this' gets you through."

Concepts and feeling aside, there's just a sheer mountain of Cyberpunk data to get through, spanning three sourcebooks and numerous supplements with them. Cities are mapped right down to minutiae - use your own technology access to find scans of Cyberpunk sourcebooks and you'll see what I mean. The amount of data swamps what CD Projekt Red had to work with for The Witcher, and while it's a gift of a resource, laying all of it down takes time.

But time they've had. There's been a small team beavering away on Cyberpunk 2077 ever since the game was announced in 2012 - an announcement done to attract talent to the studio, which isn't something CD Projekt Red has to worry about now. When I visited CD Projekt Red in 2013, to learn the studio's history, there were roughly 50 people working on the game. I don't know how large the team grew after that because when I returned as a fly on the wall during The Witcher 3's launch, I wasn't allowed to see. This is because of CD Projekt Red's reinforced silence surrounding the game, a way of managing expectations in a post-Witcher 3 world. Simply, CD Projekt Red is not talking about Cyberpunk until it has something to show.

Since The Witcher 3 launched, Pondsmith says CD Projekt Red has grown. "The number of bodies there has at least doubled," he says, "and now they're pretty much all on Cyberpunk. It's an impressive ton of people. I remember one trip I met the entire team in Warsaw and then went to Krakow [CD Projekt Red's smaller, second studio, opened in 2013], met the team and then went back to Warsaw again. The team has grown tremendously."

Pondsmith visits three or four times a year, hand-delivering paperwork and data - to avoid any "disasters" like the recent Cyberpunk 2077 asset theft - and spending days in endless meetings with every team. One of the reasons he believes his paper Cyberpunk game was so successful was the "tremendous" amount of research poured into making it feel real. A ranger paramedic, who had put people back together in combat situations, advised on the damage system, and a trauma surgeon explained exactly what happened when you drilled into someone's head for an implant.

As for guns: there's nothing like firing the real thing. "I just bought some new hardware," Pondsmith happily tells me, but it's as much for his Talsorian team as for him. "You're not going to write about shooting guns without knowing how to shoot guns," he tells them. "You need to go down and find out because otherwise you're going to be talking about silly things like, 'Yeah I one-handedly picked a .357 [Magnum] and fired it.' Yeah, and you broke your wrist."

How many guns he owns he won't tell me, which makes me think he owns a lot. He's got a Broomhandle Mauser, the vintage gun Han Solo's Star Wars pistol is based on, but his favourite [which he doesn't own, he has since clarified] is an H&K MP5K. "It's the shorty equivalent of the Uzi and it's a beautiful gun," he assures me. "When we go down to Vegas I go out and shoot them then because they're illegal as hell in most of the United States."

His son is also a fan of weaponry, albeit medieval, and owns several swords and bows. "The joke is that if someone broke into our house, the biggest pause would be everyone in the house deciding what they were going to kill them with, between the swords, the guns, the crossbows..." he laughs.

Pondsmith has cast his fastidious eye for authenticity over Cyberpunk 2077 development from the beginning. And it's that, coupled with the wisdom imparted from more than a decade of making games, which makes his contribution an entire world away from the snooty indifference Andrzej Sapkowski showed CD Projekt Red during Witcher development. And all the hard work is paying off.

"We saw some gameplay stuff when I was over there last time and I went, 'Yeah this feels like I'm doing a good Cyberpunk game here; I'm in the middle of a run I would have set up,'" he says. "It's pretty flashy I tell ya. We go, 'Yeah. Yeah. Yeah! You told me this is good - but this is really cool.'"

One unexpected off-shoot of the Cyberpunk 2077 collaboration is the Witcher 3 paper role-playing game, which wasn't part of the original deal but arose after yet another phone call. "We want to do a Witcher tabletop," said CD Projekt Red, "you know anyone?"

Pondsmith was busy and doesn't do fantasy, but staring him in the face was someone who did: his son Cody, who popped his head around the door and said, "I want to do Witcher."

"My son is actually a pretty damn good designer," Mike Pondsmith proudly tells me now. "I don't know that he was paying attention when the old man was doing stuff - I didn't know he was in my classes! - but at any rate he's got a knack for it.

"The first time I realised it we were on one of the trips over to Warsaw and he was bumming along with me and I look over and he's in a bar and he's talking to Damien [Monnier - former Witcher gameplay designer and Gwent co-creator], the systems guy - a really good systems guy - and he and Cody are sitting there going at it hammer and tongs on how to implement something. They're going at it," he says for emphasis. "I don't know where he learned it but he learned it. He looks at games the way I do: he will tear them apart."

Mike entertained Cody's idea but said if Cody wanted it, he had to go and get it. "You have to do the pitch, you have to put it together, you have to convince CDPR to let you do it, the whole nine yards."

Months later they travelled to Poland, Mike for Cyberpunk 2077 meetings, Cody to make his pitch. Mike was running here, there and everywhere, but every time he passed the cafeteria where Cody was pitching, he saw a different member of CD Projekt Red on the receiving end, nodding enthusiastically. This carried on until it was company co-founder Marcin Iwinski doing the nodding, which was a good sign and Cody got the gig. He has been immersed in Witcher lore ever since. He's even apparently heading off to Witcher School - I hope he is prepared!

The Witcher paper RPG was supposed to be released in the middle of 2016, but wasn't because CD Projekt Red couldn't spare anyone to look over it. "CDPR is pretty exacting making sure it's good," Mike Pondsmith says. It's written, though. "It's actually in editing now getting cleaned up."

It's funny to think what the future now holds for Mike Pondsmith, a man who plied a trade imagining it. Perhaps what he saw in Night City scared him, because there he was, nearly 60 years old, out of the public eye at his house hidden by forest, "raising hell" with his corgi Pikachu, when CD Projekt Red landed like a meteor in his life and put he and Cyberpunk squarely, unequivocally, back on the map. At 63 years old he may be about to become more famous than ever, and like a surfer surveying the sea, he's preparing for the wave. "We're sort of expecting things to lift off," he says.

"I was actually in the process of doing Cyberpunk Red when CD Projekt Red showed up," he tells me, so he will continue with that. He'll also "probably" do a 2077 version for pen and paper in addition to the Mekton Zero game he's way behind on. In other words he has no intention of slowing down. "Lisa says I'll retire when they pry the keyboard out of my dead hands," he says.

But first, of course, there's Cyberpunk 2077. When it will be out, we don't know - 'not before 2017' is all CD Projekt Red has ever said. My guess is 2019, but then what do I know?

"Think of me!" blurts Pondsmith. "I know a bunch of stuff and I can't tell anybody. Lisa and I are likening it to the first Indiana Jones movie years and years ago. We went to a midnight showing before it was a mass release. We're in there, it's this midnight showing at this rinky-dink little theatre in Davis, California, and we watch and we're two of 12 people in the theatre, and we walk out and we go, 'OH MY GOD!' We were frothing. And it's the same thing here."

"As Lisa likes to say: 'We backed the right horse.'"