Maps and cards - the connected worlds of Carto and Myrioramas

The walls are shifting.

The man Lyra meets on the train is elderly and immaculate. He has a moustache and heavily lidded eyes. He wears a fez. Over the course of the journey Lyra learns that he speaks perfect French and that he has a mysterious pack of cards that he uses at one point to entertain a child travelling in the same compartment.

There is something special about these cards. They are narrower than ordinary playing cards, and each one contains an image - a road, a group of people, maybe a building - that can be laid next to any other card to fit together "seamlessly", continuing the picture and bringing all elements into a single shared context. Portraits that come together to form a landscape.

When the man uses the deck to entertain the child, he builds a story with each card. There is a method to it: immaculate. "As he mentioned each event, each little object, the old man touched a silver pencil to the card, precisely showing where it was." Eventually the cards will belong to Lyra, and they will help her, in some dim and peculiar way, to divine the state of things in the world about her. And they will have a name: Myrioramas.

I found the cards, the old man, the train and the carriage, half-way through Philip Pullman's recent book The Secret Commonwealth, which I read over Christmas. The Secret Commonwealth is the latest entry in Pullman's Book of Dust series, a collection of fantasy novels that continue the narrative started with the His Dark Materials trilogy. And as such these books are filled with marvels, from the animal daemons that each human shares their life with, to Lyra's Alethiometer, a sort of pocket-watch contraption that allows Lyra to find out the truth about things by interpreting symbols. I assumed the Myrioramas were, like the Alethiometer, an invention of Pullman's. They're a lovely conceit, superficially mundane and yet quietly magical in their seamless way of slotting together in endless arrangements. And then there's that name, surely made for the long loops and arcs and bows of art nouveau printing. A strange shop in a forgotten alley, a sign beckoning underground: Myrioramas!

Anyway, shortly after I finished the book, I went online to see if any fans of Pullman's had made their own Myrioramas. And that's when I discovered that people had been making them for a couple of hundred years. Myrioramas are real.

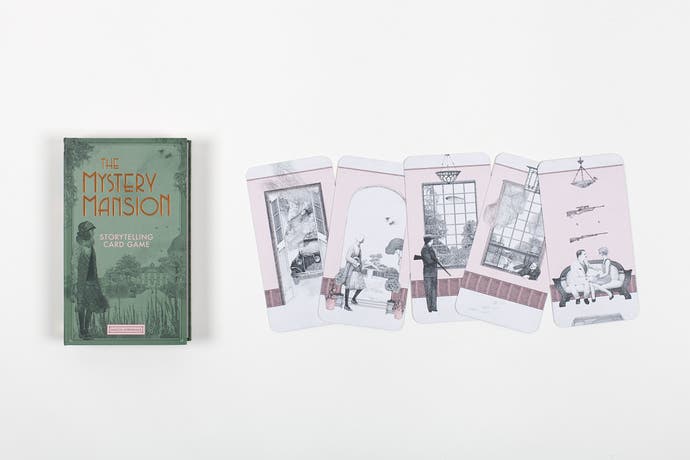

They're not just real, you can buy them on the internet. So last week I received two packs of modern Myrioramas, one called The Hollow Woods, and the other called The Mystery Mansion. They both come in funny little cardboard boxes done up to look like hardback books, and they're both taller and larger than normal playing cards. If you blew playing cards up to this size, Pullman's right, of course - they would be narrower.

I suspect Myrioramas have had many uses over the years. Both my packs are sold as sort of creativity aids - props for setting you up on the journey to tell a story. Both come packaged with a variety of ways to play them, but the way I've chosen so far has been the simplest and the closest to Pullman's - turn five cards over and find a story.

The Hollow Woods is perhaps the most straightforward - although with Myrioramas that isn't very straightforward at all. There is something of the Mythago cycle to these woods - an ancient supernatural force conjuring archetypes out of the bracken. Playing with the cards a bit it's been very clear how much the art style of a deck inflects the kinds of story it creates. The Hollow Woods is a world delivered in thin black penlines, a sort of sootiness creeping in to the dark areas where the ink gets thick. The card backs have tangled thorns, which, brilliantly, all clip together too, suggesting tales in which progress is hard won and leaves you covered in scratches. And as I turn over the cards, I see knights, unicorns and treasure chests, but also endless complications - a werewolf, steps leading into a maze, a goblin considering a cracked mirror, a giant hand coming down from the sky.

Reader, I have regularly failed to make much of these stories, such is my ossified middle-aged brain. But that giant hand reminded me of a great piece of writing advice from Steven E. de Souza, one of the writers of Die Hard. Let's say he was writing a Western. He'd take a bunch of file cards and on each one he'd write something to do with a Western - a bar, a robbery, a train. But on a few cards he'd write something odd. On one he might write "octopus". Then he'd carry the cards around in his pocket and shuffle them about day-to-day. A Western of the fairly traditional stripe, but with the chance for an octopus to turn up and surprise everyone - to surprise the storyteller!

That's what these cards are great at. As a storyteller, they jolt you out of your complacency, out of your fixed idea of how things should fit together. And the way the Hollow Woods fits together is particularly interesting in this regard. You can put any card next to any other card, but they don't so much clip into place as insinuate themselves together - the open air in one card threading with the bleached limb of a tree in another. As soon as you start stories going, these cards seem to suggest, you are never entirely in control. Things start to move of their own volition.

I think I might like The Mystery Mansion even more. Online, the stark, elongated figures in pen suggested Edward Gorey, and in the hand the deck certainly channels something of his sinister starkness. We're in Agatha Christie territory. Flappers, room keys, the high likelihood of a body sprawled on the croquet lawn. But the deck is ready to flare your thoughts in interesting directions. There's stuff for moving the story forward - a soldier type talks on a phone, some kind of object is offered to the noses of dogs - but there's much more that's just... how can I put this?

The Mystery Mansion strikes me as being a deck alive to a kind of recent absence. There's a lot of before and after in its cards that I find fascinating. A woman waits by a doorway - is she listening in or waiting to unburden herself, and is that a knife in her hand? A leg emerges from a bath. Alive or dead? What has made the gambler slumped on the bed so miserable, and how long has he been there for? The word for this deck, I think, is pregnant: it is filled with possibilities and impending action. What does it mean to make a story out of these kinds of liminal moments?

After a few days of tinkering with Myrioramas I got a little better at turning the cards into stories. I learned to use the illustrations as a sort of prompt to go deeper. A castle in the forest, sure, but what kind of castle in particular? Why is it so overgrown? Is it a new castle, still being built, and the forest magically keeps pace with it? As ever, the key to making something truly work as a story seems to be keeping yourself alive to the potential specifics of a thing - choosing the right specifics to think about. That's where you end up finding something in a story that feels like it's yours, like it wasn't there before you started. While I was doing all this, though, using randomised cards to create any kind of story, I was playing a video game that was sort of taking that idea and inverting it.

Carto seems to take the Myrioramas idea and turn it inside out. But I don't think I would even have thought of it in this way if I hadn't read the Pullman book and fallen some way down the Myrioramas rabbit hole. Carto is an absolutely wonderful game - a puzzle game with a strong narrative spine, and one that constantly surprises me not just in terms of how much it gets out of such simple mechanics, but in terms of how much of an actual adventure it feels like. Playing this in the week that Machinegames revealed it's working on Indy, here is a chance to capture a little of that character, that sense of mystery and surprise and of living by your wits, without a gun or a whip in sight.

The idea is simple. Carto is on a journey to be reunited with her grandmother. She travels across oceans and deserts and Mary Blair forests, meeting strangers and helping the communities she encounters. But she does all this by manipulating the game's map.

In fact, the game is the map. Carto is played from the top-down, sort of: you're looking across at the characters and objects, but looking down on the territory. Let's call it top-down as worked through the magical perspective of a child's drawing. But you can also pull back and move the individual squares of the map around - rotating them, swapping them in and out, completely reconnecting them. And when you change the map, the world changes accordingly. Borges! Say you need to get Carto to a forest. You could walk there. Or you could just move the forest tile next to the tile Carto's on.

And that's the simplest way of looking at things. Skip ahead now if you're worried about spoilers because this paragraph is going to reveal a few of my favourite solutions. Maybe there's an animal that lives in a cluster of a certain kind of plant. You see this plant scattered around, but clustering nowhere. So you bring the map pieces together to create the cluster. Elsewhere I opened a chest by rotating the map piece as if I was turning the tumbler on a safe. I worked my way through a haunted wood by watching for signs in nature and using a few map pieces to build an endless path. There's one truly ingenious section where an underground tunnel with an objective you can see but can't seem to reach turns out to be a long and winding road, made from just three pieces of map! Every few minutes Carto shows just how powerful this idea can be - and the kind of genuine magic it allows for.

And viewed through the lens of Myrioramas it's almost the reverse, isn't it? Instead of being given cards and being told to make whatever they prompt you to make, you're given an objective and tasked with drawing that out of the cards you're given. It feels like going inwards rather than going outwards - and it's every bit as challenging and intriguing.

You're set a task that has to be solved, somehow, in five cards. What I like about this is that it's a perfect interplay of structure and creativity. When it comes to writing, I've always felt that structure is there not to be followed from the start but to be consulted, negotiated with, when you're stuck or out of ideas. Negotiation as a form of shuffling! I think de Souza would be pleased with this.

The more I've read about Myrioramas, the more that cards seem to be just the start. Panoramic art - moving panoramas and "crankies", paper peepshows, cosmoramas, all kinds of mechanical and procedural and papercraft follies, seem to beckon. It's a world I knew nothing about and it's dizzying. Place one picture after another and be surprised: there is so much to see and discover and learn about - even with a small pack of cards.