Mario & Luigi: Dream Team Bros. review

Super Mario Doze.

When appearing on the television's broad and restless canvas, Mario games tend to expand outwards and upwards as sequel follows sequel. On these screens Nintendo has taken us from the Island to new Worlds and, most recently, into Galaxies, a curve that has often reflected the series' own pioneering design trajectory. But on the handheld's small screen, Mario's pea-green horizons have tended to shrink. Having conquered the Land, Mario and his brother Luigi have been reduced to miniscule proportions in Bowser's Inside Story, tasked with questing about in the lizard guts and arteries. Now, in this latest entry to the Mario & Luigi RPG series, we enter Luigi's mind as he's besieged by cheese dreams in a new venture into inner space.

This sort of creative subversion has defined AlphaDream's Mario RPG titles since the beginning. Much of the series' appeal is the way in which the studio's artists and designers twist the clichéd damsel-in-distress premise of the Mario myth into unexpected contours and journeys. Dream Team Bros. is no different, an irreverent and oftentimes psychedelic take on the Mushroom Kingdom that has you pulling and flicking at Luigi's face in one moment, and controlling the pair of siblings as an amalgamated super plumber the next.

It is, however, a slow start as the game tosses and turns during its opening couple of hours before settling down into any sort of satisfying rhythm. Players will find the tutorials (woven inextricably into the early storytelling) simultaneously tedious and laborious, with overlong explanations of the most rudimentary interactions that will patronise even the greenest Nintendo recruit. After all, the game's foundational gimmick is easily explained: one button triggers Mario's jump, the other Luigi's.

When exploring the game's sideways-on levels, the thinner man trails a few steps behind his sibling and, as such, you must perform jabbing one-two inputs in order to launch the pair as a single entity across the platforms. Mistimed leaps may split the pair, usually inspiring a scramble as you seek to manoeuvre them back to one another's side. Meanwhile, in the game's turn-based battles, enemies move forwards before pausing for a moment to decide which brother to attack. Players must watch for an animated tell and press the relevant brother's jump button accordingly to either leap over the incoming attack or, if the timing is perfect, to land upon the enemy's head for an evasive counter manoeuvre.

While attacking, there's further opportunity to express one's skill: strike the jump button for a second time at the exact moment that one of the brothers lands an attack and he'll bound back into the sky (or, if playing as Luigi, power up his wooden mallet) for a bonus assault. It's the simplest of ideas and yet as elegantly expressed as ever before, and the emphasis on timing over tactics gives the combat its own feel that remains quite distinct to that of conventional Japanese RPGs, despite the similarities in the framing of the action.

As well as dividing the game into the traditional halves of combat and exploration, AlphaDream further bisects Dream Team Bros. by separating the real and dream worlds into separate dimensions, each with its own interactive rules and foibles. The plot focuses on Pi'illo Island, the holiday destination that Princess Peach and her freakish yet amiable entourage descend upon in the game's introduction. The resort was named after the Pi'illo, a disappeared race of sentient beings that slipped into the esoteric Dream World many years ago. Petrified pillow relics are the only evidence of their one-time existence on the resort and, when Luigi rests his head on one, the game slings Mario into this alternate reality.

As with all Nintendo's recent games, the premise works not only to set up the story, but also to set up the mechanical conceits. Dreamy Luigi - as he's known in this dozing state - is displayed on the 3DS touch-screen while Mario is drawn into a swirling rainbow vortex and deposited in the off-kilter landscape of his brother's fever dreams. Interacting with Dreamy Luigi's face might have effects on this top screen. At one point, for example, Luigi can possess a tree and, by tugging on his moustache, a player may use its branches to fling Mario towards out-of-reach platforms. However, the developer carefully specifies where these abilities can be used, limiting the sense of satisfaction for the player as they follow the pre-scripted series of usually gimmicky interactions.

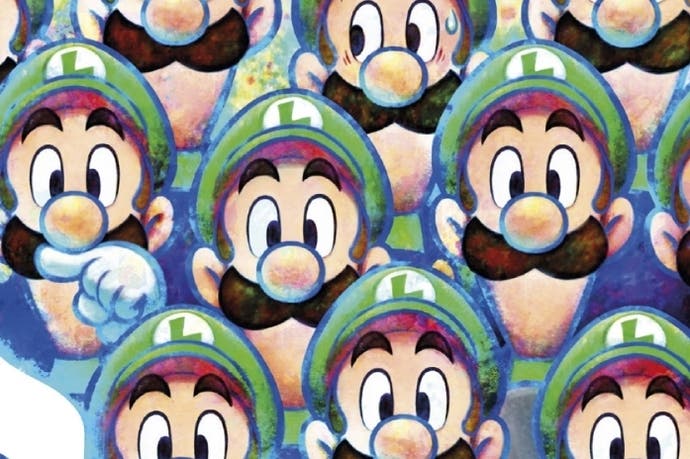

Dreamy Luigi offers a wide variety of additional support mechanisms. Send him into a constellation high above Mario and a raft of Luigis appear to form a tower to reach higher ground, or to produce a giant spinning cone to pass Mario over horizontal gaps. Luiginary Attacks - to use the game's unusually awkward parlance - are used during dream-world battles and enable you to pile tiny Luigis up into the form of a giant hammer for Mario to smash onto enemies or rhythmically build a devastating fireball. The ideas soon stack up, underpinned by the ever-compulsive RPG rhythms of earning experience points and levelling up your team members, and it's the concoction of variety and dependability that will see most players through to the conclusion.

Less successful are the game's visuals which, particularly on Pi'Illo Island, have a Donkey Kong Country-style waxy jaggedness. As a result, this is an uglier game than the previous and handsome DS title, even if the all-new 3D effect is folded lightly but usefully into gameplay during battles. The script, too, fails to live up to previous Mario & Luigi titles for whim and wit. While the usual Nintendo weight and sheen is present in the dialogue, the humour has an unexpected thinness, especially in the first half of the game before antagonist Antasma - a bat-king who shares Bowser's fondness for pointless and rather artless princess kidnapping - forms an alliance with the lizard.

This is an enjoyable but rarely essential entry to the Mario & Luigi suite, then. AlphaDream is to be commended for its willingness to build each new game around a different kernel of an idea, but, perhaps inevitably, some of those ideas will be smaller than others.