Max Payne 3 and the conflict at the heart of Rockstar's game design

Sun's out, guns out.

I'm not sure if there's another game I feel more conflicted about than Max Payne 3. The first two games rank amongst my personal favourites - particularly the second, which I think is one of the finest action shooters going. Max Payne 3 is at once better and worse than its predecessors. It has more intense shootouts, far superior visual effects, and production values to rival any Hollywood blockbuster - all of which were exactly what Max Payne strived to achieve back in 1999.

I also think it's Rockstar's most revealing creation. Rockstar has built a reputation as an architect of worlds, unparalleled not just in scope but in the nitty gritty of life simulation. No studio has taken a genre and made it their own quite like Rockstar North has with Grand Theft Auto. Rockstar may not have invented the open-city genre, but the Housers' signature is so deeply inscribed upon it they may as well have.

Max Payne is another developer's IP, and one which Rockstar sought to imprint its own personality upon. But Max already has his own personality, one constructed from wry cynicism, verbose monologues, and overwrought similes. The snow-lined streets, grotty tenements and endless nights of Noo Yoik Siddy are as much a part of his character as his tragic back-story and superhuman reflexes. Moreover, as a game Max Payne is the antithesis of everything Rockstar had built up to that point - a fast and furious action shooter that runs almost entirely on a highly specific style, whose substance only appears when time slows to a gelatinous crawl.

To mess with any of these elements more than slightly would seem like madness. Yet Rockstar has the capacity to brute-force a solution few other game developers. What results from this is a curious hybrid, one where Remedy's noir-pastiche is merged with Rockstar's fire-and-fury approach to design. And unlike the company's other games, there are no rolling hills or urban sprawls for Rockstar to hide behind. Max Payne 3 shows us Rockstar, warts and all.

That's not necessarily a bad thing. In many ways Rockstar and Max Payne are well matched, not least when it comes to rendering spectacular and thrilling gunfights. The idea of bullet-time may now be more played-out than the alcoholic ex-cop trope that Max Payne embodies, but Rockstar's combination of it with their remarkable procedural animation tech gives it a new lease of life.

The way enemies fling themselves against walls and furniture, clutching at whatever part of them has been shot, is a splendid accompaniment to the flying particles and syrupy muzzle-flashes typical to Max Payne. I love how Max adjusts his dramatic dives to compensate for surrounding obstacles, bracing his arms and shoulders for impact with any object he throws himself toward.

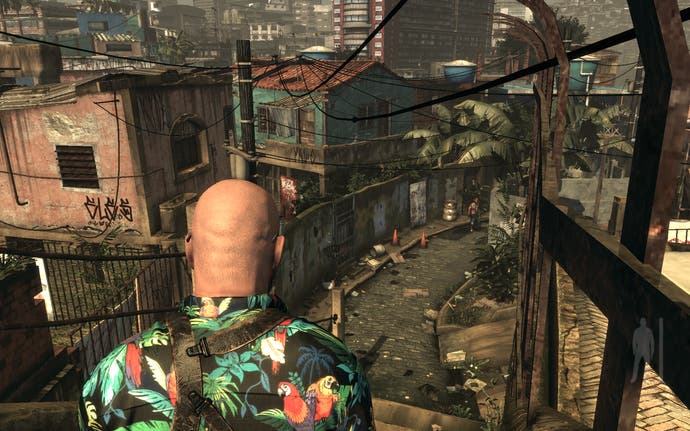

In addition, although working with a comparatively limited palette, Rockstar's eye for environments clearly extends to their Vancouver studio. Max's battle through a Sao Paolo nightclub and morning wander through a sun-drenched Favela rival Rockstar's best work in both style and detail. Even the less eye-popping stages are smartly-constructed action-sets, including a paramilitary attack on the Branco office complex, and Max's explosive escape from the fortress-like UFE police station.

As for the ideas which fit less well with the traditional Max Payne style, Rockstar do a fair amount of massaging to make them work. Max's Brazilian adventure is occasionally intercut with playable flashback missions that return the player to New York's wintery cityscape, allowing a taste of the old Max alongside Rockstar's own vision for the character. And although the comic-book interludes have been replaced by Rockstar's meticulous cinematics, Rockstar employs split-screen panels and static images as a kind of evolutionary link between the two.

The main link, however, is Max himself. The grizzled former cop may have grown a beard and shaved his head since we last saw him, but the voice remains the same, as does his world-weary attitude. Dan Houser seems to have a particular affinity for the downbeat, middle-aged Max, and does a decent job of emulating Sam Lake's elaborate narration. "Guy was smoother than an oil slick on an iceberg, and about as toxic," Max says of politician Victor Branco.

There are a few good one-liners in Max Payne 3. "I had a hole in my second-favourite drinking arm," Max says after being shot during a ransom exchange at the Galatians stadium. "First day off the sauce, and somehow I'd still ended up in the gutter," he laments after being mugged in Sao Paolo's Favela. Despite the sunshine, however, Max Payne 3's tone is considerably bleaker than the previous games. The opening is especially upsetting, as Max arrives in his Sao Paolo apartment and demonstrates in a five-minute segment just what an emotional wreck he is. By the end of the game, Max's constant reiterations about how shitty his luck is, and how everything he does makes the situation worse (even as he emerges from yet another impossible-seeming battle relatively unscathed) begin to grate.

This is where Rockstar and Remedy's styles cease to complement each other and start to diverge, fighting like feral cats in a Brooklyn alley. In Max Payne 3, the tone shifts from poetic pessimism to sneering misanthropy, providing us with precious few places to hang our sympathies. In the first game, Max's familial tragedy and framing for murder put us squarely in his camp, while in the second, it's Mona Sax who drags Max from his personal carousel of misery, giving both him and us a reason to fight again.

In the third game, there's no emotional centre either internal or external. Every character is either a twisted caricature or loses our sympathies later on. The Brancos are all various shades of wealthy reprobate. The gangsters are faceless thugs and the police are even worse. Max's sidekick Raol Pablos seems like a half-decent fellow, until he abandons Max and is revealed to be in on the scheme that causes the chaos Max must wade through. The women in the game are all objects, fake and disposable, while the one exception to this rule enjoys a brief cameo as a damsel before being conveniently sidelined. Even Max himself arrives in this situation by brutally gunning down the son of a local gang-lord in a bar.

The plot, meanwhile, offers little in the way of solace. Max Payne 3 is ultimately supposed to be a tale of redemption, but Max goes to great pains to tell us how his every action or inaction makes the situation worse. Meanwhile, the events the story doles out become increasingly appalling. We witness Marcelo Branco - an airhead party-animal and small-time crook - horrifically executed by being burned inside a pile of tyres. Toward its conclusion, the plot veers suddenly into Max working with a small-time cop (perhaps the one character with a shred of humanity) and discovering an illegal organ-harvesting scheme inside a condemned hotel. Its a sequence of grisly shocks haphazardly thrown together - the only way Rockstar can think to realign our sympathies with the pathologically melancholy and murderous Max.

These aren't the only bad-habits of Rockstar's to creep in and hurt the game. The studio's cinematic obsessions severely damage the game's flow. The action is constantly interrupted by cutscenes, to the point where there are several instances where one cutscene will end, and the player's agency is limited to taking a half-dozen steps before another cutscene kicks in. I'm not a fan of cutscenes in general, but in an action game where rhythm and flow are paramount, this constant stopping and starting is absolutely infuriating.

In the end, I think Max Payne 3's explosive action ultimately prevails, but like Max himself, Rockstar's design seems to run on brute-force, aggression and little else. It's worth emphasising these issues are not exclusive to Max Payne 3, appearing in nearly all of Rockstar's major works. Stripped of an open-world for the player to lose themselves in, however, they become that much more visible. It's an ugliness that persists beneath the stunning veneer of many of their games, one that's often justified as satirical. But good satire tends to punch upward, a thorn in the side of the powerful, whereas Rockstar's position makes it difficult to punch anywhere but down.

I find it strange that such a lucrative and wildly successful company has so little that's good to say about humanity, especially one that is otherwise capable of rendering and simulating the world we live in in such exquisite detail. Perhaps the Housers simply know something about the world that I don't. Either way, Rockstar's depiction of the world reminds me of how Max perceives the vacuous and foolish Marcelo Branco:

"Life is worth living!" exclaims Marcelo as his party boat sails through Panama.

"If you say so, pal," replies Max, downing yet another drink.