Memory and perspective converge in I Am Dead

Magnetic resonance.

There's that lovely expression for a certain kind of thinking: I'm just turning it over in my head. The good cliches have a sort of power of youth to them - they remain unbanished, unbanishable. Just turning it over. The millionth time you hear it it's as pleasing as the first time. Why? A sense of cooking, of laundry perhaps, of rocks spattering around inside the cool tube of a polisher on their way to becoming smooth. But also, the hands are invoked: thinking about something, focussing on it, turning it back and forth through the air, seeing how it feels with the fingers, noticing how it catches the light, testing the weight of the thing. Thinking with hands, with eyes.

Anyway: I Am Dead, which is coming soonish to Switch and PC, announces itself as a game about being dead. You play someone who's dead and who encounters a lot of other dead people on a quest to uncover the secret that threatens the island where they all used to live. There's even a pet dog in it who's also dead. Sparky, he's called, which may or may not be a Peanuts reference. I certainly hope so.

But I Am Dead's actually a game about turning things over, about looking at things from different angles. It's about memory and perspective, and it's also about the pieces that games are made of and, I think, perhaps the tools that make those pieces. And it's about the pieces that people are made of. Dead people sometimes. And their dogs.

It didn't make much sense when I first saw it. I Am Dead is made by the people behind Hohokum and - more recently - Wilmot's Warehouse. These are both enigmatic toy-like affairs that use striking design to lure the player into worlds where a lot of the interpretation is left up to them. I Am Dead first presented itself to me as an island, a beautiful island with a lighthouse and shops on the seafront. It looked gorgeous in its Mr Men, Clarice Cliff colours and friendly chunkiness, but it also... how to put it... had Hohokum suddenly gone 3D and open-world?

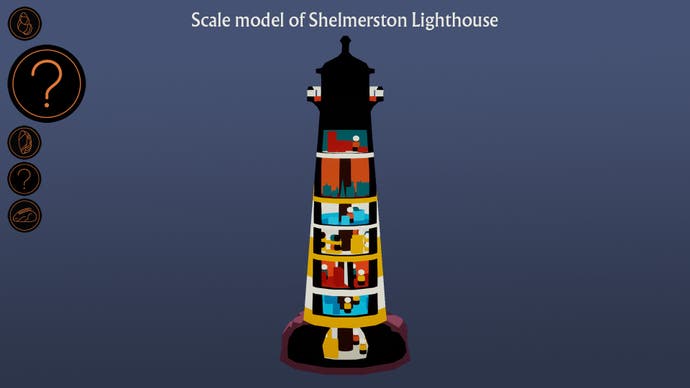

A recent demo over Discord put any worries aside. We start inside the lighthouse, and the lighthouse is more toy than location. Or rather it's both, a location built by developers who see the whole world and everything in it as a toy. The whole world and everything in it! Remember that bit.

So you can turn each floor of the lighthouse on its central spindle, and drop down floors to see what's going on elsewhere. The lighthouse has been repurposed as a yoga spa and - I wasn't taking scrupulous notes - it's now run by robots. Don't worry about any of that. What follows, as the developers suggested to me, is a sort of hidden object adventure.

And the objects are hidden in part in people's memories. Playing as a recently deceased man and his dog, your job is to connect with various ghosts on the island. You do this, beautifully, by exploring the living people who knew them. So in the lighthouse we dive inside someone's head as they are doing yoga practice. We have to first interrogate the memory and then search in the real world for the object that the memory focused on.

Interrogating the memory is perfect. You get a disk of blurred colour, and you use the triggers, left and right, to warp and shimmy the colours until images come into focus. There's a wonderfully mechanical aspect to all of this - not cogs and gears, but lenses, splitting the colours, orbing the light until it spins through various wine-bottle ripples and finally resolves. This is memory: there's something there, a flash of colour, go deeper! Go deeper! Turn it over a little in your mind. Got it!

I was not taking scrupulous notes but the memory leads to the notion that we have to go and find a medal. A medal somewhere in the lighthouse. So the object hunt begins. But it's not quite like a typical hidden object game.

Instead, you can select any of the world's objects and look inside it. This requires a bit of explanation. As a ghost, right, you have X-ray eyes. But X-rays aren't quite the right metaphor. As I watched the various objects - houseplants, wrenches, a cloudy bottle - undergo the X-ray process, it's like they've been put in an MRI. You get to move through them in sections. The developers told me they'd been inspired by watching gifs of a banana in an MRI - who isn't inspired by gifs of a banana in an MRI, not even joking - and it makes sense. There is something so pleasing about turning an object over and then slicing clean through it, watching the shapes change. Plants ooze into Rorschach blotches as you spill through their leaves. The straight lines of tools have an almost laser-like quality as you move from one end to another. Everything has an inside! A radio will have bright electronics, a light bulb will have the cold twist of a filament, a grapefruit tree - I laughed with delight - reveals the separating flesh of individual segments. A fern on a wall becomes a seismograph of dancing wood - there is a fierce musicality to moving through an object in cross-section. Even the most familiar of items is suddenly playful and slightly alien.

We found the medal eventually, inside a medal case of course, and then wandered from the lighthouse into town. Stories are everywhere here, awakened by the items you find and the memories you draw out of their mottled chaos. But they're in the environment too. Two shops in town are made from sections of the same boat. Hiding inside the hull of a ship some repairmen are secretly - oh, I shouldn't say. Just as I shouldn't say what's lurking in the water tower. This is the game, I think. You progress through the puzzles, you read the memories and find the objects, but you also have to have a feel for the pleasure of slicing and scanning, peeling away layers. MRI-viewing a world of impedimenta.

The developers admit that they make games from their own enthusiasms: chandleries, sousaphones, crustaceans, monstera deliciosa. And there's something in the MRI scanning, in the handling of delicately chunky 3D assets that makes me think that there is a pleasure in sculpting digital objects, in actually making the elements of a game using rendering tools, that the developers are trying to pass on, to share with the player. There's a secondary layer of challenges that gives you a cross-section and then sends you out into the world to hunt for it. It should be too tricky, but it feels like it fits into the kind of thing you'll want to be doing anyway - pulling everything to pieces, very non-invasively, gently teasing out the internal truths of scattered objects.

And just as Hohokum never really told you who you were or what you were doing, just as nobody told Wilmot how to organise that warehouse, there is the bold inclusion of a place for the player right at the centre of I Am Dead. Even over the course of a half-hour demo, it raises interesting thoughts about the relationship between people and the stuff they own and the stuff they leave in their wake. I don't want to say it left me with questions, because it would never be that leading, that overbearing, but there's a nice warm bubbling brewed in the brain for sure. A lot of spirituality contains a certain disdain for things of the physical world. But when people are gone, a lot of their stuff suddenly really matters to the people left behind. You want to turn it over, in your head and in your hands.