MirrorMoon EP review

All these worlds are yours.

Calico is a ghost town in San Bernadino County, California. It's a sad, creepy place, a cluster of empty shacks and dilapidated mines left to collapse in the wake of the silver rush. Wandering its dirt expanses, you really start to understand why they call these things ghost towns, too: amidst the rustling huts and decaying equipment, there's not quite enough context for your mind to reconstruct the place as it was when it was alive. Instead, you picture something stranger. Calico's the perfect prompt for your imagination to slip free and run.

It turns out that Calico is also a planet. It's in MirrorMoon EP and it's been named by a player. (They all are: the first to put boots down gets the chance to fill in the map.) I have no idea whether the player in question has ever been to the ghost town, but the ambience is surprisingly similar. On this Calico, you stroll around another quiet, uninhabited space, trying to make sense of what happened. And, hey: what happened? Grey rocks pass underfoot, a huge dark moon turns overhead, and a shimmer of angular rainfall marks the spot where, if you wait long enough, a large perspex pyramid will rise from the soil and beckon you inside. When all you have is questions, everything starts to look connected. In MirrorMoon it often is.

Santa Ragione's latest is full of this sort of stuff. It's Noctis by way of Proteus, and it's also one of the purest exploration games I've ever played: a genuine thing of wonder. The first planet you land on (let's call it the tutorial planet; the game calls it Side A) contains two or three of my favourite moments in any game this year as you pootle over its curving surface, picking up items, and working out how the sparse tooltips on offer actually translate into things you can do. It would be totally wrong to spoil the key elements of this initial experience for you, crucial to the game's mechanics as they are, so let's just say you're given a gun that isn't a gun, and, in an ingenious series of twists on FPS conventions, it allows you a degree of control over the environment that leaves you giddy with power.

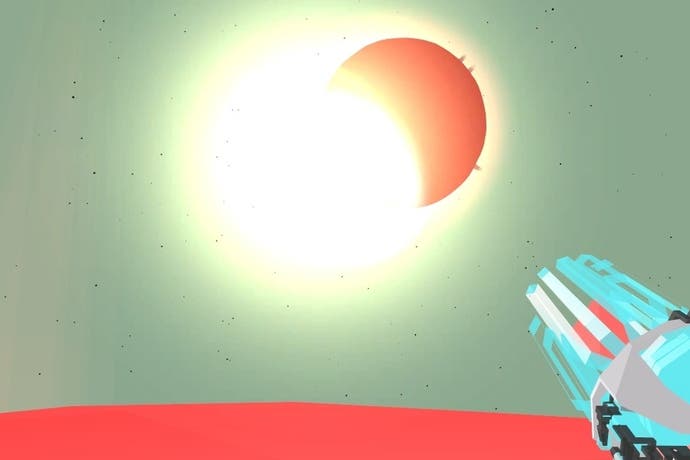

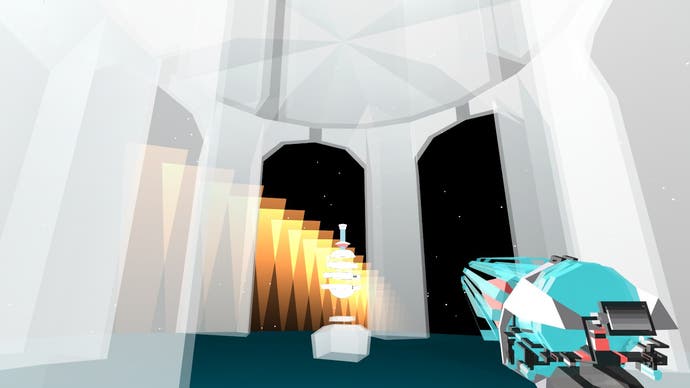

You can move across that tutorial planet, roving over its luminous pink terrain, gun-that-isn't-a-gun bobbing around in your hand, for a good half hour or so if you're approaching the game with the right mindset - tinkering with this and that, progressing through playing, wandering and wondering. There are things to activate and chains of consequence to uncover, but these puzzles are wordless and somehow convincingly alien. There's ghostly, semi-religious architecture - cathedrals of sheer plasticy neon, radio towers, miniature cupolas - and there's dormant machinery to stir. Something has occurred here, but what? And why does it matter to you?

After that first planet is done with, the game offers you a whole galaxy filled with hundreds of other worlds to visit as you tackle MirrorMoon's only openly-stated objective: tracking down a single item that could be hidden anywhere amongst the stars. It's a needle in a celestial haystack, and that sounds frustrating. In reality, the treasure hunt is the perfect excuse for wide-eyed exploration. And the exploration starts with your own ship's dashboard.

This is another glorious moment. Before you can go anywhere on the game's brimming 3D galaxy map, you must first master a screen filled with dials, switches and sliders, picked out in the voguish H&M disco colour scheme, heavy with hot pinks and cyans. What it isn't heavy with is instructions. Instead, you flip things, twist things, pull things and push things, and then try to keep track of what happens.

One of the purest exploration games I've ever played: a genuine thing of wonder

It's a delight to simply fuss around with, part Star Trek interface, part Activity Bear, part bulky 8-track, part old-school floppy disc drive. For the first time since Fez I busted out a notepad, drew a terrible wonky sketch of the instruments, and then began filling in the names as I discovered them. Eject, as I like to call it, is a particular pleasure: a smartly evocative piece of minimalist animation that makes the simple act of returning to the start menu an event.

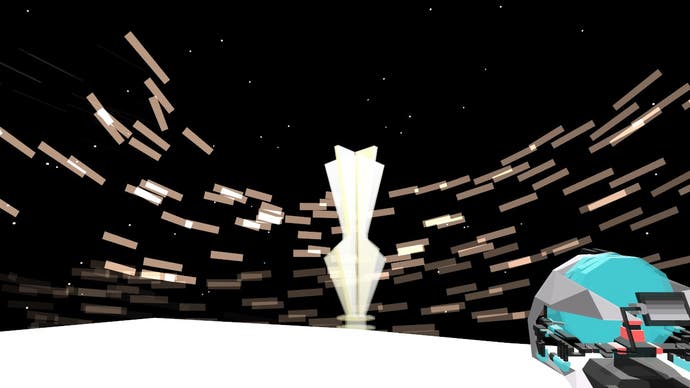

Once you know how to fly, you can travel wherever you want in MirrorMoon's huge galaxy, each star you visit dropping you back into the reconfigured FPS on a new planet where there will be fresh puzzles to solve as you try to unravel that central mystery. On a more local basis than the grand narrative, each planet has a bright white orb for you to collect before you can consider it completed. This is where the moment-to-moment challenge, although that's far too aggressive a word for the most part, comes in: manipulate the environment, fiddle with the light and shadow, uncover and kickstart alien installations. MirrorMoon has an artful jumble of puzzle pieces and each planet has a different selection. One may offer a simple scramble to find the orb. Another might have radiating pulses of light leading you from one artefact to another.

These are tinkerers' challenges rather that logicians': they're for the virtual hands more than the brain if that makes sense, and you'll often feel like you're tuning a radio needle through miles of static, or pushing parts of an orrery into alignment. Meanwhile, MirrorMoon earns the EP part of its title with a gorgeously spacy soundscape: it's the music of the spheres filtered through an old transistor speaker and, along with the 8-track back on your ship, it reinforces the sense of a trip into a digital cosmos using crusty analogue tech.

As for travelling, a simple palette swap and a few new bits of geometry can do so much. The first planet I visited on Side B was a world of ice, the next a glowing swamp with a thin fuzz of grass poking through the mud. After that I saw spectral savannahs, ancient lighthouses, and even occasional luminous references to other indie games (references that managed, somehow, not to break the spell). The low-poly approach combined with a great eye for colour does an astonishing job of delivering this strange universe, but the whole thing's also peculiarly unsettling.

Whether you're picking your way across a galaxy of black dots in a craft whose controls you barely understand or moving over the surface of a large ball, this is a game about being lost. It's about trying to zero in on a space that you often can't see, or about attempting merely to locate yourself in a near-total absence of reference points. It's a very Where the Woozle Wasn't sort of adventure, and the constant tension between exploration and orientation - with the hunt for that ultimate objective matched against the need to first understand where you are right now - genuinely invokes the early days of human exploration, where navigation was the ultimate puzzle. All true explorers spend most of the time lost, right?

You're lost, but you're not alone. One of MirrorMoon's greatest tricks is that you're exploring the same universe as hundreds of other players. You can't stop off with them for a chat, but you can see their work around you as they race to complete uncharted star systems in the hope of naming them. And what are you meant to call a star system anyway? Some people number them. Some offer terse descriptions of the treats on offer. Then there are the Daves, the B00Bs, the Calicos.

(There's a real sense of urgency as the universe fills up, but MirrorMoon ultimately has room for everyone. Once a certain number of star systems have been named, the game spawns another closed-off galaxy called a season. You can browse through completed seasons and search for their ultimate objectives, you can start a new one, or you can even play offline and keep the real estate to yourself.)

Exploring a universe that's been made just for you; most games involve this to some extent, but few give you the sense of scale, of scope, of isolation, of wonder that MirrorMoon does. This is a cosmos of crystal and flickering artefacts, a galaxy lost in the gap between radio stations. Like the very best ghost town, it can be surprisingly hard to leave.