Mirror's Edge

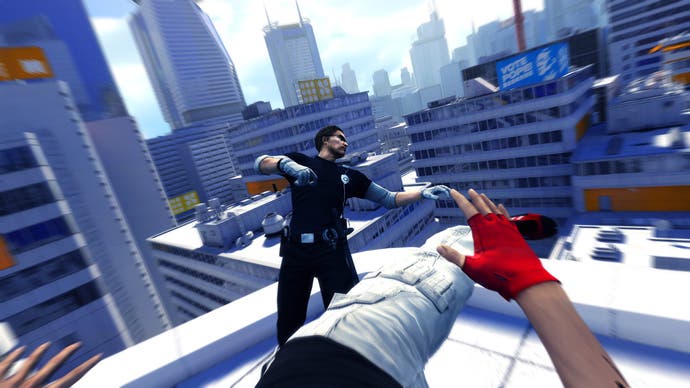

Don't shoot.

Forget blue-skies-in-games, how about press-events-not-in-dungeons? The one we're in - some sort of trendy nightspot off Union Square in San Francisco - has comfy seats and plenty of Corona, but it's still a bit out of place, and particularly as it's host to Digital Illusions' new first-person action game, Mirror's Edge, whose gameplay is sprinkled delicately across a gleaming range of mountainous rooftops and endless glass under an azure sky.

It looks a bit like an openworld game, but the focus of the sections we see is restricted to rooftops packed with vents, pipes, wire-mesh fences, substations and radio masts, and the path you take is specific. You, in this case, being a young lady called Faith (as in "leap of", given her antics), whose job it is to deliver important messages and data through the city's maze of skyscrapers while Big Brother snaps at her ankles. "To understand Faith, you need to understand the city, because she's a product of the city," says senior producer Owen O'Brien, addressing the underground gloom. "It's a city of tall, gleaming skyscrapers and clean, crime-free streets, but this comfortable life has come at a price. Gradually, over the years, people have been giving up more and more of their personal freedoms."

In the game's back-story, Faith's parents were killed in violently suppressed protests, and she grew up on the street, taught not to trust modern forms of communication, eventually becoming a "runner". Runners are "not strictly speaking criminals", says O'Brien, "but the people they work for have been criminalised, rightly or wrongly." Events in the game inevitably conspire to give Faith more to do than just deliver parcels, moulding her into more of a heroine than a Postman Patricia. "She's a heroine in the way Ellen Ripley is in Alien, or John McClane in Die Hard is a hero; they're an ordinary person put into extraordinary situations and it's what they do in those situations that makes them a hero," says O'Brien.

We quickly tune out of what he's saying though, because Mirror's Edge is very absorbing to watch. First-person games are almost always about the gun rather than the person holding it, and DICE designed Mirror's Edge as a counterpoint to that. "The first thing we wanted to look at was just getting the feeling of movement and momentum, so walking, jogging and running," says O'Brien, winning our attention again. "Very simple things, but things that haven't really been done well in first-person shooters." You don't even have a gun - instead you're told to concentrate on moving quickly, maintaining momentum through tricky environments, much as we did during the freer-flowing parts of Ubisoft's Assassin's Creed. Controls are deliberately simple: movement and view-adjustment on the analogue sticks, and then context-sensitive "up" and "down" functions on a pair of buttons (presumably the triggers - did we mention it was dark?). "Up" can be jumping, climbing, wall-running, vaulting, or grabbing hold of something above you, like a zip-line, while "down" can be used to perform a power-slide under a low object, or to break your fall with a parachute roll. The only other control mentioned is Sixaxis tilting for balancing on beams on the PS3.

Fail to string these things together properly and you will lose momentum, and may fall off things or get shot if someone's chasing you. If our demo was anything to go by though, the main penalty is not enjoying yourself as much: it looked very good, especially as our DICE handlers navigated a busy rooftop in a fluid sequence of stylish manoeuvres clearly inspired by the best bits of the Bourne film series, the building site bit at the start of Casino Royale, and other recent examples of cinema's sudden fascination with parkour. One big problem when applying this sort of thing to games, though, is making it obvious where to go without simplifying or regimenting your options too much and without confusing you. DICE's answer to this is something called Runner Vision.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)